Hello! If you've been enjoying our work and you believe in the importance of high-quality journalism, then boy do we have a deal for you: supporting The Londoner for only £1.23 a week for the first three months (£4.95 a month).

In return, you'll get access to our entire back catalogue of members-only journalism, receive eight extra editions per month, and be able to come along to our fantastic members' events. Just click that red button below.

Quiet — can you hear? Just on the threshold of sound, near impossible to make out: the scrape of a chair being moved, the whisper of silk on floorboards. A snatch of conversation, perhaps, or the residue of laughter, hanging in the air like smoke from a just-snuffed candle. You’ve just missed them, you see, the Jervises; they’ve slipped out of the room, leaving their half-eaten clementines and nibbled mince pies.

The Jervis family are to be found in Dennis Severs’ House, 18 Folgate Street, one in a row of handsome, straight-backed houses built for the area’s silk merchants in the first half of the 18th century. That’s the only place you’ll find them, mind, as they’re entirely fictional, borne of the mind of Severs himself. Growing up in Escondido, California, he initially travelled to London to study law before giving it up to become a porter at Christie’s, where he grew familiar with precious antiques and fine art, as well as to conduct tours of the city with an open landau.

Already Severs was interested in communicating emotional rather than literal truths: he dressed, with typical theatrical flair, in a black silk top hat and tailcoat, and told wildly exaggerated accounts of the capital’s history. He bought the house in 1979, shortly after it was saved by the Spitalfields Trust, who were attempting to preserve the fast-disappearing heritage of the area as, street by rust-bricked street, it was demolished. It quickly became Severs’ residence, personal nightclub and immersive art performance; more than that, it became his life’s work.

It’s difficult to adequately describe the house, a place whose very existence demands to be felt, to be experienced. Put roughly, the conceit is that several generations of the Jervises inhabit it, and that each room represents a different period in time, and in the family’s fortunes, ending with them living in poverty and squalor in the attic. These are arranged as tableaux, ornately detailed and knowingly anachronistic. Visitors are not allowed to take photographs, nor are they supposed to speak. Severs promoted his attraction in the press to great success, though anybody who didn’t seem to get it was turfed out, their money thrown out after them; a florid piece of myth-making that Severs himself propagated (though it seems mostly apocryphal). Today, it’s staffed by professionals, mostly former art students, who ensure that attendees are accessing the rooms in the correct order.

Though calling the Jervises “fictional” is accurate, it doesn’t feel like quite the right word to describe them, or anything about Dennis Severs’ House. The family haunts the property, returning day after day, night after night, as does Severs, who died in 1999 from an AIDS-related illness. The latter speaks to us, both through the medium of the house itself and through the notes that guide visitors through the experience; as if he, too, has just stepped out. For the evening tours, actors perform versions of his script, and the sound effects (horse’s hooves, street bustle) were recorded by Severs back in the day. Some things are different, though: the used chamber pot and rotting meat that he would place around the house to provide authentic odours have gone, though the experience of moving through 18 Folgate Street remains a kind of sensory possession.

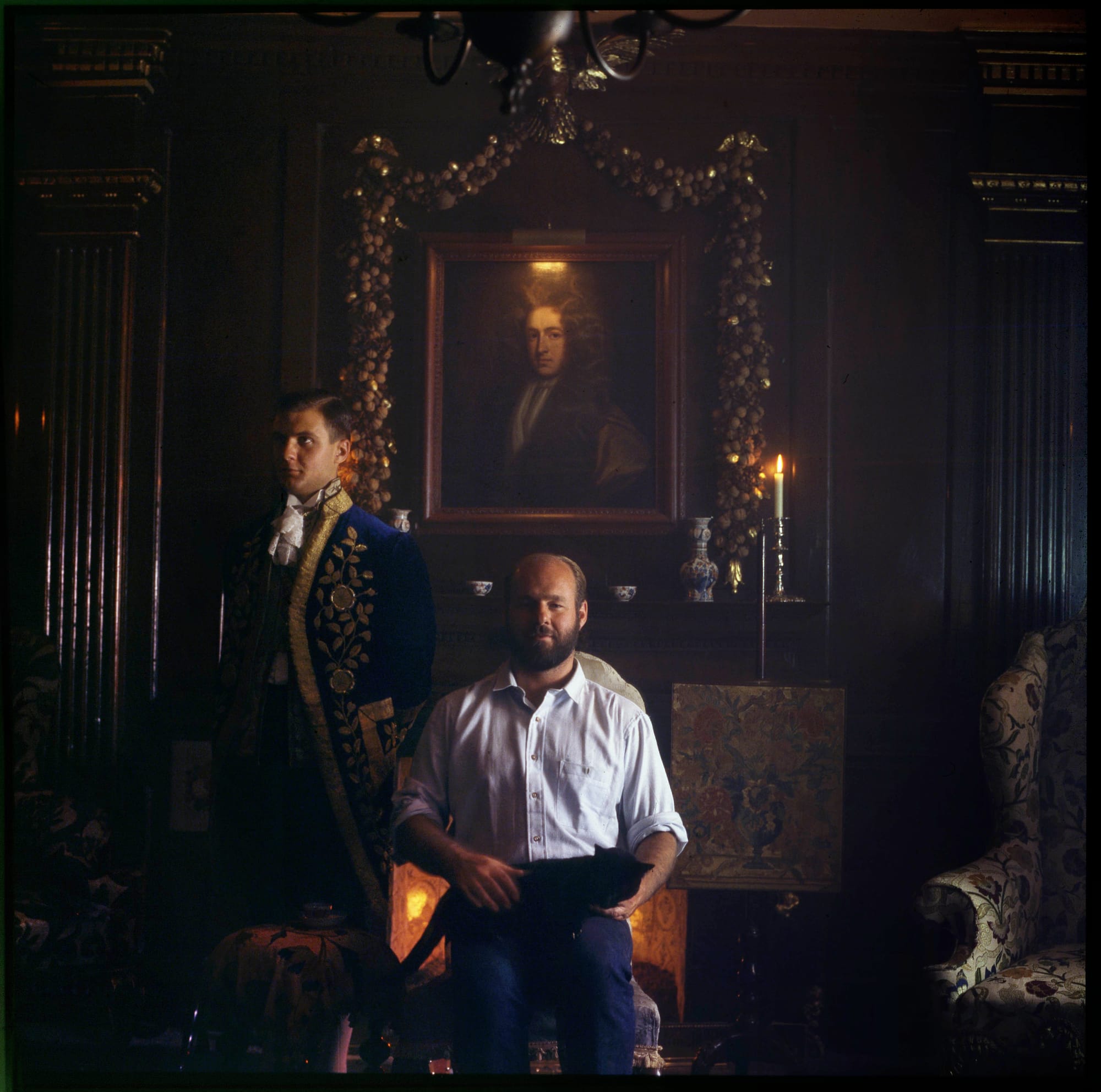

The starting place, and the room where I meet house director Rupert Thomas and creative director Amy Merrick (responsible for the house’s styling), is the dining room. The scene of the Jervises at the height of their wealth, it’s almost dizzyingly opulent, heady with luxury, all velvet chairs and dark panelling and scallop shell sconces and wood smoke. In the middle of the table, a black swan, eyes cruel, beak red as arterial blood, resides over a table laid with torn pomegranates, silver knives, goblets of claret and china bowls of Turkish delight; above it, a crown of pines — a “kissing ball”, the pre-Victorian forebear of the Christmas tree — drips with pears and oranges.

The tradition of dressing the house for Christmas was started, as with most things here, by Severs. “Dennis did this every year as well,” Thomas tells me, thick-rimmed glasses reflecting in the firelight. “It was very much a party house. It saw lots of action.” He cocks an eyebrow slightly, referencing the orgies and bacchanals Severs used to hold there, using the smoking room’s 18th century punchbowl to serve booze. “It doesn’t see action in that kind of way now, but we retain this tradition, which is mostly of an early Victorian Christmas. Amy does everything bespoke, really, from scratch.”

Stuck for (very) last minute gifts? Never fear: with a gift subscription to The Londoner you can get 44% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll handle the rest.

It’s a process that’s year-round in its commitment, with Merrick scouring everything from antiques dealers to Instagram accounts. The actual dressing for the festive period happens in around four days in November, a huge undertaking by Merrick and two other members of staff, not including the time it takes for her to bake dozens of festive biscuits, sweets and pies.

The former editor of World of Interiors, Thomas was hired by the house’s chair Marianna Kennedy (who, he says, “saved the house” after convincing Severs to leave it to the Spitalfields Trust in his will) after he was involved in a photoshoot the magazine staged there. He refused, he tells me, though when they asked again — and when nobody else seemed forthcoming — he stepped forward.

Sorry to interrupt, but we need your help: can you support The Londoner in continuing to produce the in-depth reporting on the capital that we're known for?

We've made it easy too: with our new member discount, a Londoner membership is just £1.25 a week. If you like what we're doing, please consider lending us a hand.

Now, he’s utterly at ease here, tweaking the folds of drawing-room curtains, noting a new stocking which Merrick has hung on a bedpost, removing his beige trench coat and draping it on a nearby antique chair, as if he’s just returned home from work. He met Severs towards the end of the latter’s life, and describes him as a challenging yet brilliant figure, arrogant and charismatic in equal measure. Severs was above all “a real outsider”: a modern person in an old house, an American in London, a gay man in a homophobic society, a flesh-and-blood human living in a fairytale. He embodied extremes. “He lived like a Georgian,” Thomas says. “He lived with fires, lived with candles,” though, in typical Severs fashion, it was an image of a Georgian who enjoyed leather bars and Soho gay clubs.

Part of the charm and delight of the house is how it turns the usual division of authentic versus artificial on its head: unlike a regular museum, the open fires here are real, yet the ornate fireplace, as Thomas points out, is a replica fashioned on a chicken-wire skeleton. Even the pears on the kissing ball are not quite what they seem. Look closer, and you’ll see they’re plastic. “I would hang fresh pears,” Merrick tells me in her soft American accent, sighing slightly as she taps a specimen.

But when they started using portable heaters to lessen the icy winters for volunteers, the pears began to rot at an alarming rate, “They started dropping every few days, and you would never know when that was going to happen... So these are actually stand-ins, and tomorrow we’ll have the [versions] from an artist in Canada I commissioned to make incredibly beautiful, hyper-realistic papier-mâché pears”. Other perishables, like a boiled egg with toast, are replaced every day. The worrying thing, Merrick says, is when she comes to refresh biscuits after a few weeks, only to find that somebody’s taken a bite out of them.

Severs wasn’t merely aware of the contradictions at the heart of the house; he embraced them, enfolded them. There’s a delight to the 1990s computer, tucked away in a bedroom, or the Yankees hat hung on a peg in the hallway. Nowhere is the dichotomy more beautifully encapsulated, though, than in the work of Simon Pettet, a ceramicist and Sever’s partner who created some of the house’s most exquisite objects before his death from an AIDS-related illness in 1993 at age 28. He had met Severs when the latter was 18, outside Heaven, and the two got a taxi back to Spitalfields. “He brought lots and lots of young men back here,” Thomas says, “And never told them what they were coming to, so they would come into here in the pitch black, and some ran screaming.”

Yet right from the start, Pettet was “completely smitten”, both with Severs and the house. His ceramics are intricate and quietly masterful, taking inspiration from the Delftware that the two would buy cheaply in the city’s markets yet making objects that were utterly his own; like the tiles that initially look to be 18th century but turn out, on closer inspection, to be decorated with portraits of the couple’s friends (and cat).

As a child growing up in sun-bleached California, Severs was enamoured with English literature, particularly Dickens, and loved to watch black and white adaptations of the classics. Perhaps this is the reason the house has a filmic atmosphere, the sense of narrative embodied. For Severs, the Jervises had become manifest. “He didn't live here alone in his mind,” Thomas tells me as we walk through the high-Victorian glamour of Mrs Jervis’ bedroom, the sheets on the four-poster rumpled as if somebody has just slept in them. “They really became very three dimensional” (this may be authentic; credit on the website as the “honorary house guest”, artisan James Howlett does still sleep at 18 Folgate Street).

Before I leave, Thomas lets me in on a secret. Downstairs in the kitchen, across from the huge Victorian stove, is a door normally closed to visitors. It’s hidden in the panelling, which is original — extremely rare, in a house of this age and in this area, which usually lost such details when they were subdivided into cramped flats — and behind it, a small kitchenette, with a fridge and boxes of wine. Pasted onto the back of the door are dozens of images, mostly of Queen Elizabeth II, the drag queen Divine and, by far outnumbering the other two in the number of photographs, black cats. Historic alongside modern, outsider alongside establishment, tenderness alongside strangeness: it’s a mix that feels quintessentially, unmistakably, at the core of Dennis Severs’ House.

You can visit Dennis Severs' House in its Christmas get-up until 11 January, though it's worth seeing it at any point in the year (in summer, for instance, lavender is scattered around the edges of the rooms). Book here.