Happy Saturday to our lovely readers. Having a good weekend so far? Here's one way you could make ours even better: by becoming a paying supporter of The Londoner. Researching and reporting stories like the one you're about to dive into takes a large amount of time and resources, and we aren't backed by billionaires or private equity firms (as much as that might make things easier, we're fiercely devoted to our independence and integrity). That means it's only through reader subscriptions, from people exactly like you, that we can continue to exist.

That's why we've set ourselves the rather ambitious target of reaching 1,000 subscribers by the end of October. To be completely, radically honest with you, we're about 120 members away. It's a little scary, a little bold. But we think, with your help, we can do it. If you think London deserves quality coverage — if you think you deserve quality coverage — consider backing us for just £4.95 a month for the first three months. Becoming a supporter gives you access to all of the members-only content in our archive, as well as putting you at the vanguard of a media revolution. Let's do this together.

Hello and welcome to The Londoner, a brand-new magazine all about the capital. Sign up to our mailing list to get two completely free editions every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

When Chamutal first decided to home educate her kids in the early 2000s, it wasn’t exactly the done thing. There were only around 10 or so families in her North London “tribe”, as she calls it, a ragtag troop of midwives and artists and eccentrics.

“Most of them had their babies at home. Most breastfed at least to three years old, some to five or six or seven,” Chamutal tells me plainly, as we sit drinking coffee around her cluttered kitchen table in Edmonton. She’s brash but generous, with browny-blonde hair and a habit of going off on tangents. As the more mainstream parents took their four-year-olds off to reception, the tribe decamped to Epping Forest. They’d spend months each year in a makeshift campsite, doing arts and crafts and encouraging their kids to get acquainted with the elements.

“I would classify them all as strange people, us included. You don’t get normal people doing this!” laughs her youngest son, Mika, 18 with cropped blonde hair, as he interrupts the story. “But now you do”, insists Chamutal, yanking back control of the conversation. “This is the main difference.”

Since the pandemic, the number of children being home educated in London has surged. Numbers rose from 9,540 in 2022 to 11,780 in 2024, and in Tower Hamlets and Bexley figures rose by 63% and 58%, respectively. Data from before the pandemic is patchy, but 2014 figures suggest there may have been as much as a fivefold increase over the past decade. What was once a niche, alternative lifestyle appears to be entering the mainstream.

So what’s behind the rise in home education in London? And how have the lifestyle and teaching methods developed by early home educators like Chamutal changed since those muddy September mornings back in the early noughties — in short, what does home schooling look like in London in 2025? When I put out a call to the city's home educators, a long line of parents were keen to have their say.

'We know lots of families who don't vaccinate, like hundreds'

In an empty cafe in a community centre in Peckham, I meet Michelle. In her 40s, with centre-parted dark hair, she’s proud to tell me how she de-registered her now 13-year-old son after he started to find school upsetting as a six year old. He was acting out, getting himself hurt and finding trouble. She tells me how her route into home education took place through a network of Facebook groups, a common phenomenon. “Where I live in London, I was aware that there’s a big community.”

For Michelle, the increase in home education — she baulks when I refer to it as homeschooling, arguing the term holds authoritarian connotations — is partly about the availability of information. She helps to organise a group called Educational Freedom, which provides resources and encouragement to similar families. But it’s also about escaping what she sees to be an unkind and overly restrictive approach to educating young children. “We keep making it earlier for the sit-down academics,” she says, shaking her head. She’s disparaging about how kids now face formal tests as early as reception. “My child clearly wants to bounce.”

In London, it's this kind of ideological aversion to the schooling system which often drives home educators. When the Department for Education administered a survey last year, the most common reason for London parents to home educate was “philosophical”: a response option chosen by 23% of home educators in inner London local authorities, compared to 14% in England and Wales overall.

For a lot of the parents I speak to, these “philosophical” reasons involve agreeable-enough sounding notions of indulging children's interests, spending time outdoors and not giving kids exams at a young age. Lots only enrol their kids when they reach 6 or 7, stretching out those precious first few years of parenting as much as possible. But the same anti-authoritarian leanings which can drive parents to pull children out of school can also give the scene a more alternative edge. “We know lots of families who don't vaccinate, like hundreds,” says one parent, who doesn’t want to be named.

“There are huge communities of, I suppose, quite non-mainstream people in London, many of whom home educate and don't take their kids to the doctor if they're ill,” they tell me. “They just take responsibility for it themselves.” They describe New Year's Eve raves in King's Cross for home educated teenagers, at which kids had been known to show up with measles.

Judith, another home educating parent, laughs when I ask if her home education scene has anti-vax or conspiratorial aspects and says that hasn’t been her experience. But her community does contain people from a wider range of political and religious backgrounds, she says carefully, compared to a more inward-looking past when, “I read the Guardian and lived in Stoke Newington and we all went to the Spence bakery”. She home schools for what she agrees would be seen as philosophical reasons, and says that a lot of her 14-year-old son Ben’s education takes place at co-ops: rented spaces across the city, at which groups of parents cluster together to run lessons.

The photo she shows me looks suspiciously like a classroom, only one with children of lots of different ages all in one room. “I loved school,” she tells me. “I was really into it.” But the churn of exam-shaped hoops she had to jump through as a child “devalued education” for her, and so she chose to teach Ben at home using a combination of co-ops, museums, textbooks and tutors.

To account for their own lack of knowledge, parents can use a combination of online classrooms and resources. BBC Bitesize provides home education packs, whereas groups like Educational Freedom compile links to online and in-person teaching groups. But live lessons with qualified professionals are expensive, and still require extensive co-ordination for the parent. “My husband works two jobs, that’s how I afford it,” admits Michelle.

Judith follows what she calls a “child-led” approach. But the problem with being led by children is that they aren’t always wise to their best interests. I didn’t have the greatest level of foresight as an eight-year-old, and if I were to have guided my own education I suspect I may have steered it towards Halo and dinosaurs. If your child decides their new thing is going to be sparrows, how do you separate out a fleeting obsession from a worthy focus for their education? “Well,” Judith says carefully, “if he was really interested in sparrows, we would go and look at lots of sparrows. We would go to the free animal sanctuary,” and only then decide to start buying textbooks. She emphasises that it’s about instilling curiosity.

Enjoying this edition? You can get two totally free editions of The Londoner every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

'He was out by the third day... and he requested to come out'

But while many in the capital still home educate on philosophical grounds, an increasing number of parents are now turning to it as a last resort. On a sodden September afternoon outside the Houses of Parliament, I meet Penny. She withdrew her 13-year-old son from school last year, after he was excluded for repeatedly attempting to run away. “They couldn't meet his needs,” she says wanly, and so reluctantly withdrew him from the school. He's currently awaiting the results of an autism assessment.

A teacher herself, Penny is one of several I encounter who have decided that the school system which employs them is no longer right for their children. “[They] are getting worse and worse,” says Marita, a former teacher based in south London, who claims that rising class sizes make it challenging to deliver a proper lesson. Due to declining birth rates, class sizes in London have in fact fallen more in London than anywhere else in the UK since 2017. But with London schools struggling for staff and often merging different institutions into one, schools do still regularly flag to the government that they're exceeding the legal limit of 30 pupils per class. This coincides with an upsurge of children with special educational needs in London — a 15% rise in inner London since 2016, at the same time as teaching assistant numbers have declined by 13%.

Wendy Charles-Warner is the chair of Education Otherwise, a home education charity founded in 1976, and began teaching her own children at home in the early 1980s after what she describes as a failed attempt to integrate “problem” children into well-performing state schools. “Never in the whole of that history have I seen such a huge sea change” in the home education community, she tells me over the phone. “We are now a group of people where more than half of us don't want to be here,” she says, referencing a recent survey administered by the charity which found that 54% of home educating parents did so because they felt schools could no longer meet their needs.

It's a problem of special educational needs provision, she says, at the same time there's been a “cultural shift” in parenting practices. “When I was a young mother, it would have been incredibly unusual, if a child said 'I'm not happy at school', for a mother to say 'let's home educate'.” But with many of the young families I meet reporting this piece, that's exactly what happened.

“Hubby wasn't really on board,” says Michelle, despite wanting to home educate Dara from the beginning, and so he went to school. “He loved reception,” she says, but ended up getting into trouble on the first few days of year one. “He was out by the third day,” she says, “and he requested to come out.”

Michelle is keen to convey an idyllic image of life as a home educated child in London. But when I chat more with Mika, whose college experience this year marks his first encounter with the mainstream education system, he’s candid about some of the challenges. “My work is incredible,” he says dramatically, when I ask how he’s been finding the transition. “But the difficult thing for me to adjust to has been deadlines and time management.”

Child-led home education often takes the form of a freewheeling series of projects and obsessions, so without regular homework and clear work boundaries it can be harder to adapt to a more regimented environment. It can clearly work well for people: Ben and Mika come across as thoughtful and articulate, with the support of attentive parents.

But it can also go wrong. I make contact with a man I'm calling Damian, who’s keen to share some of his more negative experiences of home education in the late 2000s. “I think she thought she was doing the right thing,” he says, telling me how his mum pulled him out of school after he started skipping lessons. But rather than fostering a sense of curiosity, he found himself bored. “I spent almost the entire time playing video games or wandering the streets,” he says, before eventually going on to do his GCSEs in his early 20s. “I found it really hard going to college afterwards,” he says, unused to the strictures of a regular routine. Local authorities would check in a couple of times a year, but they were content that he was learning.

Sorry to interrupt — we promise we'll be quick. We just wanted to take you on a quick behind-the-scenes of what we do. Peter wrote this piece using old-fashioned, boots-on-the-ground methods. He went out into the city, away from his laptop, to dig out the story and find the people he needed to speak to. We think the results speak for themselves.

But this sort of in-depth journalism doesn't come cheap. That's why a lot of media companies have given up on it, instead churning out clickbait articles that have little connection to London or those who live here. But we believe people are still willing to pay for deep-dive, properly reported work.

Already, around 880 of you have signed up as paying members to prove us right. But now we have a big target: 1,000 members. We've made it easy too: with our summer discount, a Londoner membership is just £1.25 a week. That's less than a daily coffee.

We aren't funded by billionaire oligarchs or huge companies. And that means we need the people of London and beyond. If you like what we're doing, please consider supporting us.

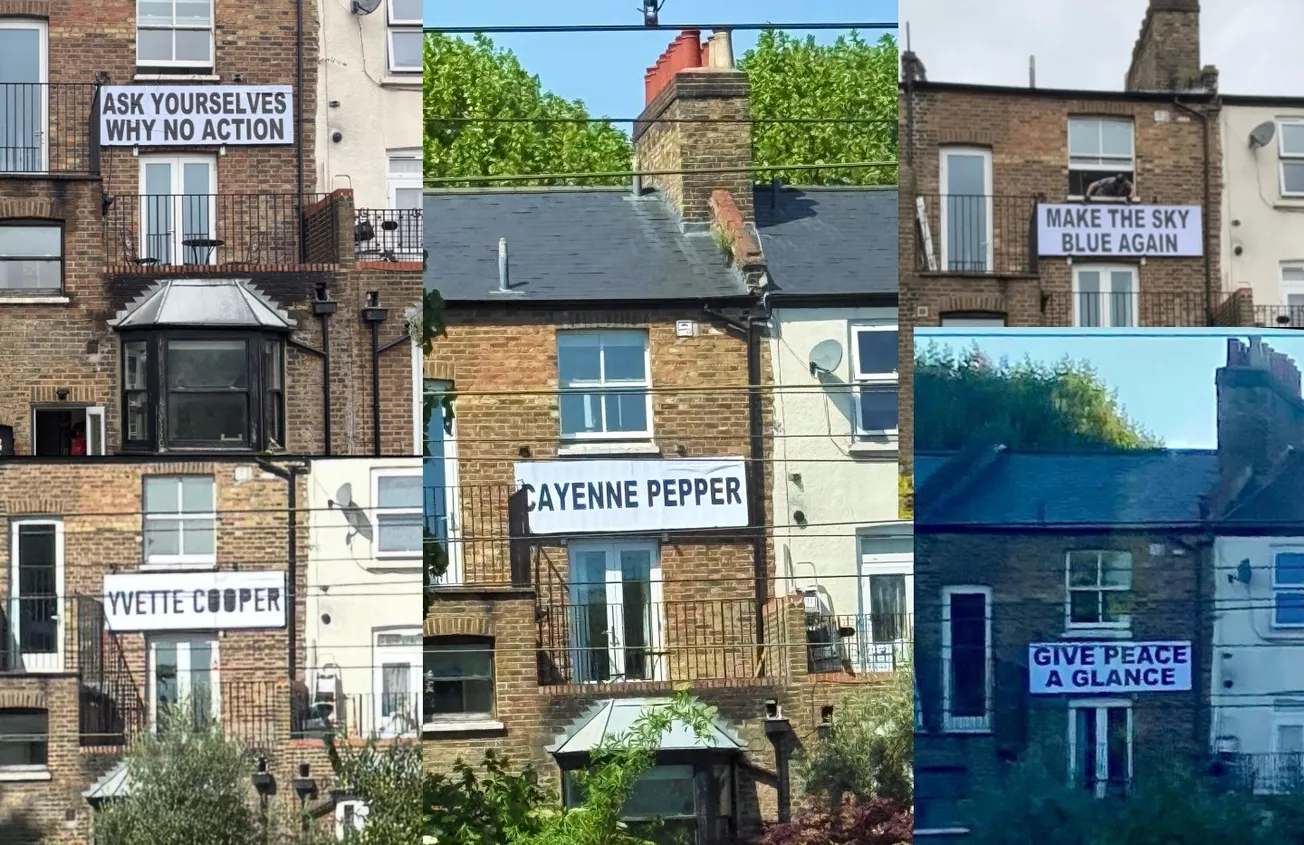

Concerns about safeguarding are never far away in discussions around home education. And just as the lifestyle is entering the mainstream, a new piece of legislation — the Children’s Wellbeing and Schools Bill — is promising to regulate the sector. It includes a mandatory register for all children in home education, an expanded remit for the local authority to assess the quality of education, and a requirement for parents to provide detailed information about non-parents involved in their children’s education.

Educational Freedom frames the bill — which is about to enter its third reading in the House of Lords — as an ineffectual “attack” on home education. On a blog post on their website, the organisation argues that as Sara Sharif [a 10-year-old who was abused and murdered by her parents in 2023, after they removed her from school on home education grounds] “was known to school, social workers and EHE [local authorities], this bill would have not changed her outcome. We hate saying this, but she would have still died.”

But the safeguarding concerns are clear. In a review of 41 cases of child abuse published last year, the Child Safeguarding Practice Review Panel suggested that, in those victims who were home educated, "the protective factor that school can offer was missing from their lives.” This had “serious, sometimes fatal, consequences for their safety and welfare”.

Nonetheless, many home educating parents are concerned about how such regimented requirements will fit with the peripatetic lifestyle they’ve carved out for themselves. Does a zookeeper qualify as an educating non-parental adult? Should online tutors have to provide families with personal details?

Almost all the parents I spoke with were angry at the potential quantity of information they might have to share. And it’s true that a maximalist enforcement of the requirements currently being hashed out in the House of Lords may be intrusive. But it feels, too, that the increased regulation of home education is an inevitable consequence of the practice becoming so prominent. London’s home education scene is a long way from those tribal retreats in Epping Forest all those years ago, and as dissatisfaction with the regular schooling system seems set to endure, its numbers may only go up.

If you enjoyed Peter's piece and want to get sent long-form reads on under-explored communities in the city, why not join up as a Londoner member today? This means you'll get weekend long reads like our piece on the strange death of east London's radical bookshop and Monday briefings like our exclusive on the south London Turkish restaurant given a £2.5m fine by the council for a misplaced vent delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Londoner and reach over 20,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below