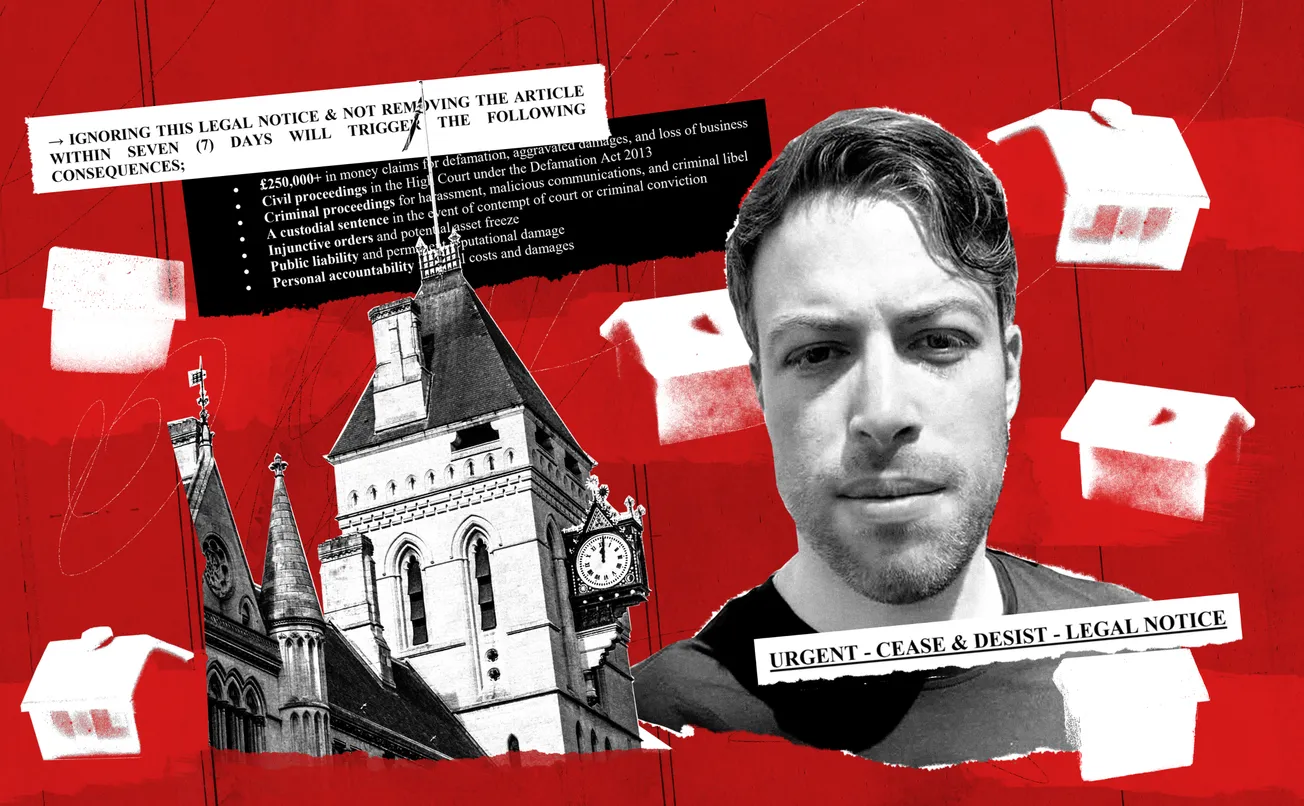

Dear Londoners — Yesterday, we went public about being sued for £250,000 by Claudio Di Giovanni, a wealthy Italian holiday-let grifter we exposed back in August.

His campaign of threats, anonymous emails and legal action has been going on for months, and we've had countless agonised conversations about whether to take the step to speak about it — it's not the kind of thing a newspaper would normally do. But we decided that our readers deserve the truth about how media works in this city. If you start revealing what rich and powerful people are up to, there are often consequences.

In response, dozens of you have joined up as members to help us fight this case, and we were so encouraged by your heartfelt comments on the piece. Reader Dan Holty summed it up well when he said that we were "clearly doing something right if you are causing this type of ruckus with people like this"; we were similarly buoyed by the words fellow supporter Moira Newell, who wrote: "Keep up the good fight."

It was also heartening to see that our message been shared by journalists such as David Aaronovitch and Ash Sarkar, as well as barristers like Matthew Scott.

You can still read about it here. If you're already a backer, then thank you so much — please continue to share with your friends. And if you haven't yet signed up to support local media that's unafraid to report on what's really going on in this city, please join today.

TV producer, author, cannabis expert, pioneer in the world of street-side falafel — Patrick Matthews has lived more lives than most. But at 72 years old, he’s taken on a new mantle: north London folk hero. Now, when he walks the streets of Kentish Town, strangers greet him by name, and tell him to “keep up the fight”. The fight in question? Running a poolside cafe.

Matthews is at the centre of an increasingly fraught battle over the future of the cafes on Hampstead Heath, Queen’s Park and Highgate Woods, a dispute that has united everyone from local schoolteachers to Bafta-winning actors against the City of London Corporation, the local authority who run the parks. And now, there’s the potential that the corporation, one of the oldest and most influential bodies in the capital, might face a historic embarrassment in the courts. But how did things get so out of hand over a few lattes?

The revolution will not be caffeinated

The cafes at the centre of the saga lie across five sites in the same stretch of genteel north London. There’s one by Parliament Hill on Hampstead Heath run by the Italian ice cream van supremos the D’Auria family for over 40 years, one in Golders Hill Park run Cosmin Stuparu, and three sites in Parliament Hill Lido, Queens Park and Highgate Woods run by Hoxton Beach, the business Matthew has run with his wife Emma Fernandez for just under a decade.

The couple came in to fill the void in the aftermath of the City of London’s bungled 2016 attempt to give the same cafes over to the coffee chain Benugo, who pulled out after a backlash from locals. The residents of NW5 take their park-side cafes seriously; so seriously, in fact, that Matthews still recalls the interview he had with Doug Crawford — then part of the “cafe working group” set up after the Benguo affair — who drilled him on his planned menu and pricing. A 75-year-old retired management consultant, Crawford is, in his own words, “a stroppy local who gets very agitated”.

For the next few years, everything was going swimmingly. The cafes run by Hoxton Beach doubled (and in one case even quadrupled) their turnover and slowly morphed into a community institution. Karen Smith, a long-time regular of the Parliament Hill Lido branch turned supporter of the campaign, says that “everybody knows Emma and Patrick”. A bespectacled, 52-year-old schoolteacher with a no-nonsense air, Smith explains that locals enjoy “the slightly shabby nature of it… It feels like a space that is very welcoming, and it is a family.” Heaving with customers eager for its £6 hot meals, the cafe has a distinctly community feel: an eclectic mix of paper lanterns, amateur art works and a hodge-podge of deli items.

But in late 2023, there was a changing of the guard at the City of London. An American named Bill LoSasso took over as superintendent of the Heath and the corporation’s other north London parks. From the get-go, he didn’t seem to be the biggest fan of the cafes he now oversaw. Matthews recalls how, when LoSasso and an entourage of City of London staff came from the Guildhall headquarters of the corporation to the Highgate Woods cafe for an event, the new superintendent refused to enter and sent in an assistant to collect his food instead.

Then the news came in July last year that the City of London was exploring a “remarketing” process for the cafes (nobody seemed able to say what a remarketing process was, nor why it seems to follow different rules to the normal tendering process most councils run). Put simply, the City was going to choose a different provider to take on new long-term leases for the cafes it runs, an opportunity that no doubt would allow it to increase revenues.

The people of NW5 were fuming. For many, it felt like a similar battle a decade before, when the corporation appointed a private firm that selected one of its clients, cafe chain Benugo, as the winner of the bid. “It feels like déjà vu, very much like déjà vu,” as Crawford puts it. Back then, after a community campaign, a petition with 20,000 signatures and the support of a local MP (a little known junior shadow minister called Keir Starmer), Benugo pulled out.

Nevertheless, the present-day City of London Corporation didn’t seem too interested in involving any locals in the bidding process. Almost no information was shared about it to campaigners, citing commercial sensitivity. When campaigners asked why the cafe working group hadn’t been consulted, they were informed by the City that it had been dissolved several years prior — much to the confusion and shock of all its active members. To Crawford, it’s evidence of a “certain arrogance” that the City has. “They refused to make even basic details of the tender process public… They see themselves as above scrutiny.”

In its defence, the City argued that the current operators were allowed to submit bids, which would be assessed not just on how much money they could offer, but also on “community value” (though when asked, they didn’t give any guidance on how this would be calculated; they didn’t plan to consult anyone in the community). Still, the operators made their bids, despite the gnawing feeling that they were unlikely to succeed and that, as Matthews puts it, the corporation was going to “give it to who they wanted to give it to”.

A new threat

Karen Smith found out that the current operators were being evicted after a single message arrived from the D’Auria family: “We’ve lost the cafe”. The decision had been expected nearly two weeks before, though it was only announced on 19 December. Her phone immediately began buzzing uncontrollably with messages from fellow outraged campaigners. “You know how lawyers like to send out letters at 5pm on a Friday? It felt very much to most of us that the calls were being made, possibly in a cynical way, knowing that two weeks of any campaigning would be lost due to Christmas,” she says. “I'll be honest, I was fairly apoplectic.”

In the aftermath, it turned out that not only had Hoxton Beach not been chosen; it hadn’t even been shortlisted. According to the consultants handling the process, its “concept decks” outlining its business vision for the space were too “rough”.

It was like a gut punch for Matthews and Fernandez, whose entire livelihoods were tied up in their community cafes. “We were beyond devastated,” as Matthews puts it. “Our 11-year-old daughter has spent a huge chunk of her life at the Lido.” In their stead, four of the five cafes were being given to Daisy Green, an upmarket cafe chain that serves Australian-inspired food. “I’m not sure what there is at the heart of it,” as Matthews puts it. “It just seems to be very expensive coffee with mashed avocado, eggs Benedict or something, except really expensive with a slightly annoying vibe.”

If the locals had been miffed before, that was nothing compared to how irate they were now. Many went from watching from the sidelines to becoming amateur sleuths. According to them, something stunk about the whole process. For one, Davis Coffer Lyons, the company that the City of London hired to manage the remarketing process, lists Daisy Green among the brands it has worked with in the past. “One could argue there’s a conflict of interest there,” Crawford argues.

Then there’s the new operator itself. On its website, Daisy Green — founded by couple Tom Onions and Prue Freeman — describes itself as having “grown organically” from its early days as a “street food collective… with two vintage ice cream vans and three tricycles”. But dig beneath the marketing copy, and the firm seems to have some pretty wealthy backers — Daisy Green is listed as a client on the website of venture capital firm Volpini Ventures. The reference was later removed from Volpini’s site after Smith pointed it out to Freeman, who said it was an inaccurate “quirk of technology” (Freeman did not respond to the Londoner’s multiple inquiries). As of last year, the “independent family business” operates 21 different sites, boasts a turnover of £26.9m and pays each of its co-founders a salary of nearly £300,000 a year.

If the City of London thought the backlash would be a short-lived spark, it was turning into an inferno. A petition grew — now with over 22,000 signatures and getting backing from celebrities like Benedict Cumberbatch and James McAvoy — and the saga made its way from local newspapers to the nationals. It got so bad that John Foley, a City of London councillor, called the saga a “PR disaster” and accused the corporation of having “zero interaction” with any of the locals in a public meeting.

Would it all become too much for the City of London? Was the 850-year-old organisation responsible for some of the city’s wealthiest districts about to back down? But as it turned out, the corporation was far from done.

Enjoying our deep dive on the fraught battle for Hampstead Heath's cafes? Good news: there's plenty more where that came from. The Londoner produces great reporting and peerless writing about everything from education to politics, crime to conservation in the capital, as well as features like this one. And what’s more, half of everything we publish is totally free to read. This means you'll get weekend long reads like our piece on the enduring appeal of the Regency Cafe and Monday briefings like this one on the civil war over Hammersmith Bridge delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.

The corporation strikes back

The City’s first broadside was an opinion piece in the Guardian and an open letter by alderman Gregory Jones, the essence of which essentially boiled down to: please stop bullying us. The letter claimed that the corporation’s staff — and those of Daisy Green — had been subject to unspecified “hostility, intimidation and harassment” at the hands of the cafe campaigners.

Matthews bristles at the claims: “They make it sound as if I'm going onto the heath and sort of pushing lifeguards into the pond, or kind of attacking them with a spade or something. It’s absolutely nuts.” He says the only thing he can think of that might explain the comments is that some locals had been rumoured to be going around Daisy Green’s other locations, taking photos of prices on the menus and “sort of arguing or something with the staff”.

But that wasn’t the only tactic up the City’s sleeve. For their next move, they relied on one of the oldest tactics in history: divide and conquer. To start with, they offered one of the original operators — Cosmin Stuparu — the chance to take over a different cafe; the Hoxton Beach site in Highgate Woods that Daisy Green had no plan to take over. He readily accepted.

Then there was the D’Auria family. They’d been at the core of the fight, and their cafe was the hub for many of the campaigners. But the cafe, started by 80-year-old patriarch Alberto in the 1970s, had become more of a side business to their booming ice cream van trade. In the end, they reached a deal with Daisy Green and the City: in exchange for the D’Aurias stepping aside, the family’s name and staff would remain at the site, as would much of their menu of Italian classics (including D’Auria-provided ice cream). Nobody could give us a full breakdown of what the nature of D’Auria’s settlement was and whether it had involved any remuneration for the family. And so, with that, Hoxton Beach were the last of the original operators standing.

But they wouldn’t go down without a fight. You see, one advantage of running a cafe on the edge of Hampstead, one of the most elite neighbourhoods in the capital, is that your regulars include some of the country’s top lawyers. Matthews was able to put together a legal team and, when I spoke to him on Tuesday, revealed that a letter before action had been filed with the City of London. This has secured them a week-long delay to their planned eviction date, which was originally this coming Monday (2 February). But the City of London isn’t backing down. "Hoxton Beach have refused to leave the cafes they occupy despite their tenancies having been terminated,” a spokesperson declared when the news broke. Anything, including getting a court order and bailiffs to force them out, is on the table.

Whatever they decide to do, it doesn’t seem like the locals will take it lying down. “They don’t own the Heath. They are its custodians, they are there to look after it. I don't think they understand [it],” Smith tells me. “I think that they sit in their little gold tower of the Guildhall, and [think] that they're dealing with the Square Mile. And they're not.”

If you enjoyed this story on the inside story of the battle for the Hampstead Heath cafes, why not join up to our mailing list and get two completely free editions of The Londoner every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No fluff, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.