🎁 Want to give something thoughtful, local and completely sustainable this Christmas? Buy them a heavily discounted gift subscription. Every week, your chosen recipient will receive insightful journalism that keeps them connected to London — a gift that keeps on giving all year round.

You can get 44% off a normal annual subscription, or you can buy six month (£39.90) or three month (£19.90) versions too. Just set it up to start on Christmas Day (or whenever you prefer) and we'll do the rest.

To read today's piece, you’ll need to be a full-fledged supporter of The Londoner. By the end of this year, we're trying to reach the lofty goal of 1,250 paid members. Currently, we have 1,118. Can you help us get there, and continue to produce the in-depth reporting on the capital that we're known for?

We've made it easy too: with our new member discount, a Londoner membership is just £1.25 a week. If you like what we're doing, please consider supporting us.

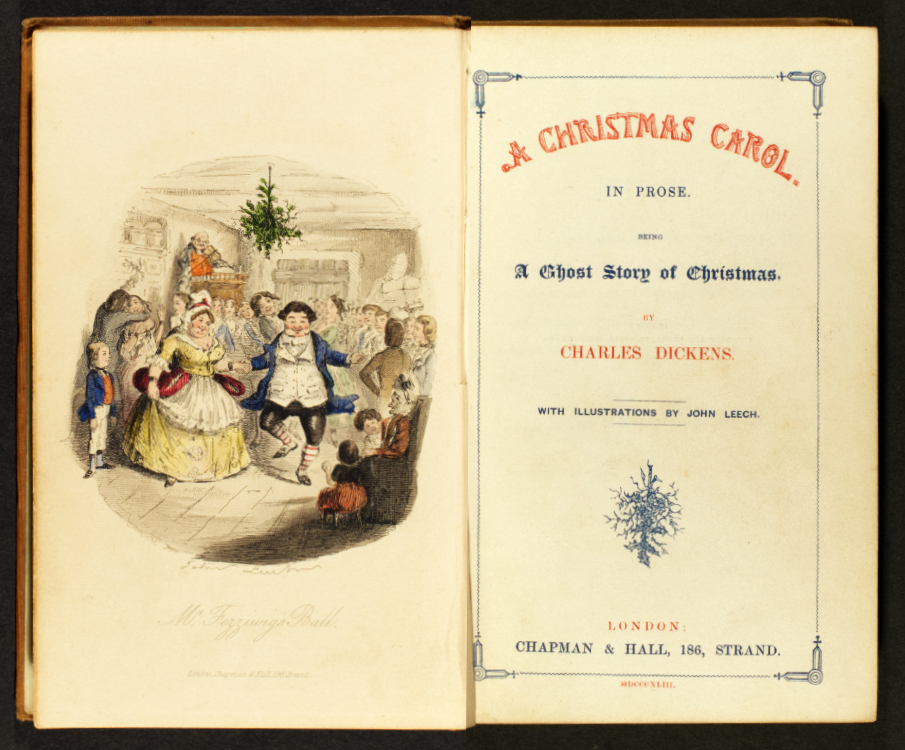

One story, probably apocryphal: when Charles Dickens died on 9 June 1870, a barrow girl near Covent Garden market was heard to exclaim “Dickens dead? Then will Father Christmas die too?” Another story, probably true: when Dickens finished writing A Christmas Carol in November 1843 after six weeks of furious work, he was seized with a “perfect convulsion of hospitality” and insisted on hosting a series of festive dinner parties. Dickens, in these anecdotes, is not merely an author who popularised Christmas traditions; he’s the embodiment of the season itself. Indeed, he seemed like a man possessed by it: jittery with nervous energy, he wrote during the day and spent his nights walking miles along London’s streets, accompanied only by the hiss of the gas lamp and the rumbling carts of the night-workers.

We, in turn, repaid the favour. It’s hard now to imagine a Christmas without A Christmas Carol, though Dickens was hardly the originator of a certain brand of mid-Victorian nostalgia for earlier, vanishing Advent customs, nor the first to fuse them with the ideals of Christian charity. But what sets the novel apart is, quite simply, how good it is: eerie, funny, heart-breaking and heart-warming in equal measure. The story has its Damascene conversion, of course, but it also has ghosts both jolly and spooky, sinister n’er’do’wells, angelic children, time-travel, raucous parties. These reasons are no doubt at the heart of why the book has been adapted so many times — Dickens himself toured a version suited for listeners, staging one-and-a-half hour long readings throughout his lifetime (between 1853 and his death, he gave 127 such performances).

London deserves great journalism. You can help make it happen.

You're halfway there, the rest of the story is behind this paywall. Join the Londoner for full access to local news that matters, just £8.95/month.

SubscribeAlready have an account? Sign In