The interior of Romford Greyhound Stadium resembles years of selective breeding between a social club, a carvery and a high street betting shop. It’s a bitter Tuesday afternoon, and the bar is mostly serving cups of tea for the two dozen punters who have arrived early. A receptionist explains how she grew up nearby and, as a teenager, used to work as a ‘Coral Girl’, trotting out with a sash after races. Outside, a coach pulls up, unloading a crowd of pensioners who wander past the bar and into the on-site restaurant where they’ll spend what remains of the day.

Romford has lost much of its unique character over the years. It’s no longer the UK garage hotspot it was in the early 2000s, but its deep blue Coral Stadium has persevered. The cover of Blur’s 1994 album Parklife, a sarcastic paean to British blokeyness, was shot here. Back then, Londoners had seven greyhound races within the M25 but, one by one, they began to close: Hackney, then Wembley, Catford, Walthamstow and Wimbledon. Last week, Crayford announced its imminent closure due to "dwindling support", leaving only Romford.

On the way in, there’s a plexiglass sign proclaiming the stadium’s multispecies ‘Hall of Fame’. Notable entries include Chopchop Hope, a racing bitch; Roger Kent-Barton, a respected bookmaker who got three years in 1982 for handling stolen shotguns; and Archer Leggett, the original owner who, in 1936, was persuaded by an explorer that it would be a good idea to race cheetahs (it wasn’t).

Some of today’s attendees were regulars before the Suez crisis and remember when over ten million people ‘went to the dogs’ each year. The deceased are here too, about twelve of them apparently, their ashes scattered on the track’s green, ovoid center. “In 1966 England was playing Poland in a friendly, and they wanted to reschedule Wembley Greyhounds,” recalls Ray Bourne, a dog owner who attended his first race in 1950, “but Wembley Greyhounds wouldn’t reschedule, they had 50,000 people there.”

As with any gambling enterprise, malicious miracles happen. Dean Tennant, renowned by staff as the loudest man at the races, is provoked into a memory of his friend Miles, who had been given five grand from his soon-to-be father-in-law for an engagement party. Tennant found him sprinting around the balcony like he’d won the lottery. “He says, ‘I had my last five hundred pounds on that dog.’”

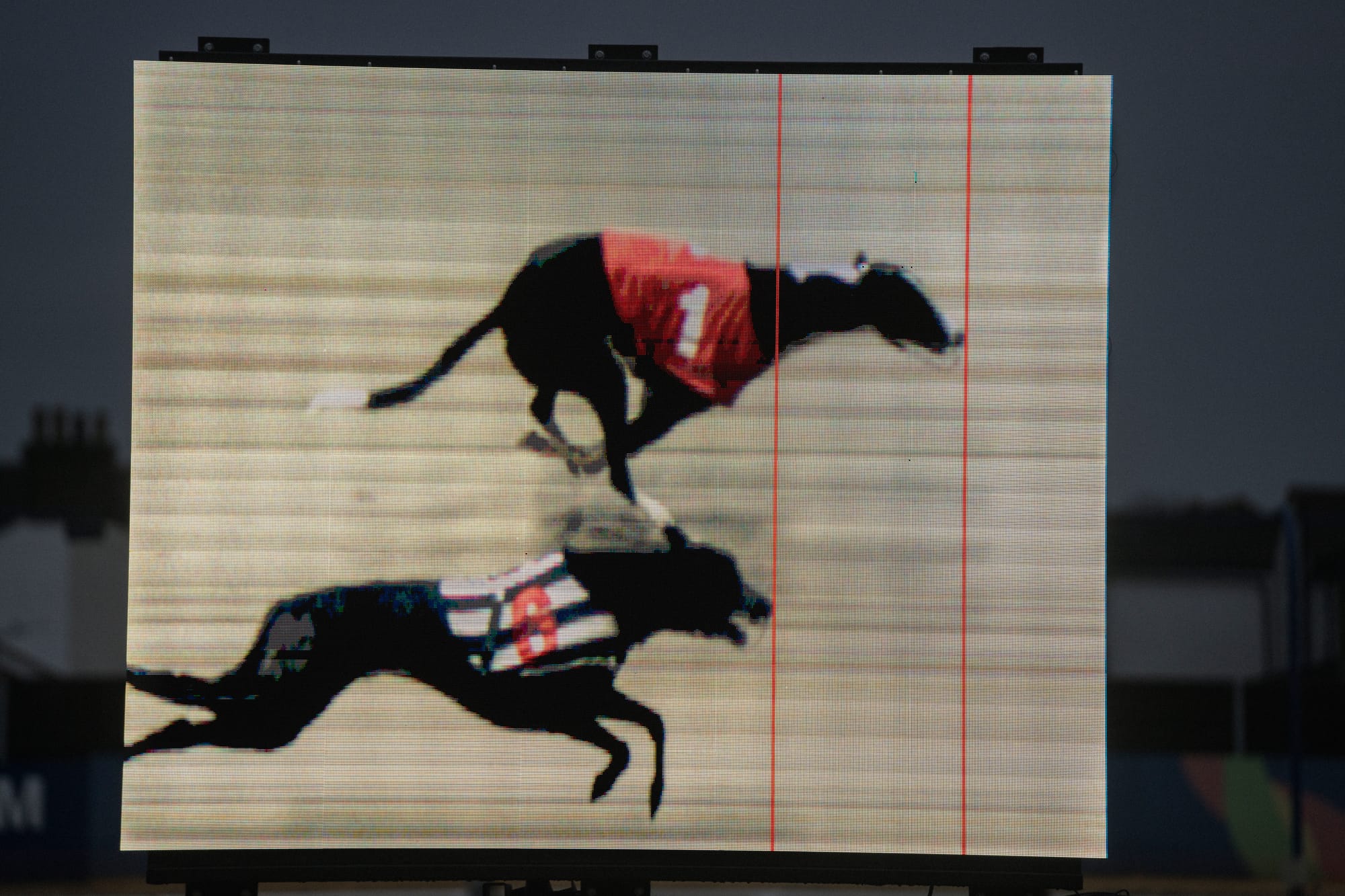

Below us, down in the bowels, some fifty greyhounds wait on-site for their turn, and five are led out into the traps. Most of the time you can see who’s won by the first turn, Tennant explains.

“Six coming away smartly, four showing early pace here, Magical Becca on the hatrick, Portsmouth Pedro second, one on each side, Portsmouth Pedro trying to close in behind, the lead is down to a length on the final turn, Magical Becca in front, Portsmouth Pedro on the outside, both digging deep… and that’s a hatrick.”

There are diminishing returns in greyhounds these days. Before its 88 years of operation ended in 2017, auditors found that Wimbledon Stadium was making annual losses of £1.4m. But according to the stadium manager, Karen McMillan, Romford has remained profitable, partly due to a multi-million pound refurbishment in 2019 and a focus on providing a diversity of services. Overall, Romford will take more from the restaurant and bar than from the bets, especially on the weekends, when over a thousand revellers pull up at the gates.

Among the weekday faithful, there are three intersecting categories: gamblers, owners and trainers. Gamblers often become owners themselves — usually as part of a syndicate — and pay trainers to keep their dogs housed, trained and in shape. Racing dogs are awarded run money, which goes towards kennel costs. A few win big in national derbies, but most owners are lifestyle hobbyists. When a greyhound retires due to injury or old age, it has to be rehomed. Sometimes owners adopt; sometimes they don’t. The Greyhound Trust, a charity that prepares greyhounds for domestic life, are currently experiencing a major drop in takers.

At the bar, I meet a trainer called David Welch, or ‘Disco Dave,’ as my contact list now attests. Welch is also a professional dancer and got to the final of Britain's Got Talent, 2015, with his troupe, Old Men Grooving — ironically, they lost to a dog. About 80% of racing greyhounds are bred in Ireland, and according to Welch, training starts at 14 months on a schooling track. Some trainers will school a little earlier, first the pups watch the older dogs, some of them know straight away, others just stand there.

The next session is vital. Trainers hold the dog’s front legs up, turn their head to face the hare and, as it comes past, they let go. “That's the moment of truth,” Welch says. “That's the moment where you know if you've got anything, or you've got nothing.” Welch runs a relatively small operation and only keeps 20 greyhounds; other trainers keep hundreds. He struggles with the emotional demands of the job, particularly when it comes to rehoming non-racers. “I hate it. I’m just the old man who cries because his dog goes. It’s the one part of the sport that I find horrific… most trainers will say they’re not pets, they’re racing machines and become pets later in life… it’s hard, especially when you’ve bred them and learnt everything about them.”

Welch is able to train dogs because he owns land. Nevertheless, greyhound racing has always been perceived as ‘the poor man’s horses’. His friend John Young, a man in his seventies, cuts in and tells me he’s been coming for half a century. At fourteen years old, Young arrived in Edmonton, North London and struggled to make friends. One day, while out walking with his dad, they came across Walthamstow stadium and saw thousands of people marching to the dogs together.

Young’s parents were both proud to call themselves working class, but over the years, he’s seen a shift in the way punters perceive themselves. “Actually,” he says, “not many people here would happily admit to being working class, we’re all lower middle class.” And with that comment, protruding like a loose thread from a hairy, tattered rug, the history of greyhound racing unravels — an eternity in dog years.

Unlike most breeds you see nowadays, greyhounds have populated the British Isles for over a thousand years. The labrador retriever, the country’s most popular pet, was first introduced in the early 1800s. By contrast, historians have argued that the Vindolanda tablets, dating back to 1st century Roman Britain, contain evidence for hunting dogs — likely greyhounds, or ‘celt hounds’ as the Romans called them. During the 10th century, King Howel of Wales made their killing punishable by death. King Canute protected their ownership, along with William the Conqueror a generation later.

Greyhounds are supposedly the first breed mentioned in English literature, kept by Chaucer’s monk in The Canterbury Tales. Likewise, Shakespeare writes them into Henry V, The Merry Wives of Windsor and The Taming of the Shrew — ‘Lucentio slipped me like his greyhound’. The rules of ‘coursing’, the tradition of watching dogs chase down prey, was first constituted under Elizabeth I, but the sport wasn’t automated until the 1920s, when the mechanical hare was brought over by an American socialite in flannel trousers called Charles Munn.

Greyhound racing lurched forward rapidly from there. The first track was at Belle Vue, Manchester, in 1926, and the culture mushroomed outwards. By 1928, national attendance had reached 13.7 million — 20.8 million by 1932, when the national population was less than double that figure. “From the beginning,” Keith Laybourn writes in his extensive history Going to the Dogs, “[greyhound racing] upset many of the middle class, local authorities, religious denominations and the National Anti-Gambling League”.

Bookies and punters (Photos by Harry Mitchell)

Dissent soon rose from the middle classes to establishment opponents who, according to Laybourn, distrusted it for creating a “something for nothing mentality’’ amongst the working classes. Churchill was an outspoken critic. After WWII, going to the dogs remained popular, but struggled against legislation. Betting and licence taxes were imposed (measures horse racing largely avoided). Around London, greyhound tracks were acquired by mobsters, notably the Clarkenwell-based Sabini Gang and ‘Big Alf White’, who bought part-ownership of Hackney Wick Stadium after doing jail time for leaving a man with one eye.

Throughout the 1950s, other forms of gambling began to proliferate. Then 1960 brought the Betting and Gaming Act, which allowed betting shops to open, tempting the public away from stadiums and into the darkened, uniform hubs that now dominate deprived high-streets across the country. The ubiquitous adoption of television also contributed to the dogs’ decline and, more recently, disturbing revelations of animal cruelty.

Such scandals have plagued greyhound racing for decades now, but the decisive scandal manifested eighteen years ago,in the form of a builders’ merchant from Durham. In 2006, The Sunday Times reported that David Smith had been running a “euthanasia factory” at his home in Seaham, taking dogs that had been deemed unfit to race and shooting them in the head with a bolt gun. Their corpses were dumped and buried on a one acre plot outside his house.

“Within a year the bodies have gone,” Smith, told an undercover reporter, outlining how he’d work his way across the field, planting dogs like seeds, before returning to where he’d begun. Reporters from the Northern Echo covertly photographed Smith pushing wheelbarrows overflowing with little limp bodies. It was conservatively estimated he may have killed over 10,000 dogs. When I contacted Smith’s company, a woman answered the phone. “Whatever was published was very exaggerated” she said, “and that’s why I won’t speak to anybody. Bye!”

After the Seaham incident a regulator was established in 2009: the Greyhound Board of Great Britain, whose acronym sounds like an extremely patriotic TV channel. This self appointed regulator has the difficult task of overseeing the welfare standards of a declining industry that campaign groups say is inherently cruel. When Mark Bird, a former Met police officer, was asked to become managing director of the GBGB in 2017, he initially refused. Bird didn’t have a sentimental connection to greyhound racing other than getting food poisoning at Romford and throwing his guts up over the barrier at the train station. “But then they said I’d have a free hand… and I said if you want the sport to survive we have to completely nail welfare.”

Transparency is important to Bird. Since 2017, GBGB has published data showing the number of deaths and injuries per year. Licenced kennels receive biannual unannounced visits from stewards and checks from regulatory vets. Bird also has to deal with the problem of doping. This ranges from overfeeding dogs so they underperform and boost their odds (on site, staff uphold a mitigatory “vomit protocol”), to full-on narcotic boosting. Cocaine is a pan-mammalian feature at the races: the 2017 winner of a top Irish derby was banned after testing positive for cocaine three times in four weeks.

But for many, Bird’s best efforts are insufficient. “We know that about 6,000 pups are being killed in Ireland because they don’t make the grade,” says Moe Kaur, a spokesperson for the Alliance Against Greyhound Racing (AAGR), referencing a recent RTE investigation, “so the UK industry’s complicit in that.” After the RTE investigation, the Irish greyhound industry brought in a new traceability system. However, last year, figures obtained by Greyhound Action Ireland showed that over 1,500 dogs born in 2022 remained unaccounted for.

Kaur cites expert reports that say repetitive racing on oval tracks causes injuries exclusive to racing dogs, “from as young as two years old, these dogs get arthritis”. When Kaur, a former doctor, began working with greyhound rescue in 2014 she was shocked. They had huge bald patches, urine burns, fleas, scars, limps, bone swelling, she says. “I was seeing this constantly.”

There have also been major incidences of neglect. Last year a GBGB inspector made an unannounced visit to a trainer in Yorkshire to find four dead greyhounds and several others emaciated in "heavily soiled" kennels. After that, Bird was challenged by someone from the Greyhound Forum who asked: “Mark, can you assure me that will never happen again?” He told her he couldn’t. “It can happen in such a short period of time. If you have a mental episode, the last thing you’re thinking about is the dogs.”

I return to Romford on Friday night. It’s better attended than my first visit, with a broader range of ages — more like a football crowd. In the restaurant, a group of retired boxers are enjoying a charity fundraiser. At the bar, punters drink from pitchers of beer, occasionally popping to the bathroom to celebrate a win. Outside on the stands, amidst the shouting, a group of local women in their early twenties have come in lieu of a big night out. One of them wins a tenner on a dog called Bacon Roll, and the ‘Romford Roar’ envelops her. “See that feeling, it’s better than most things.”

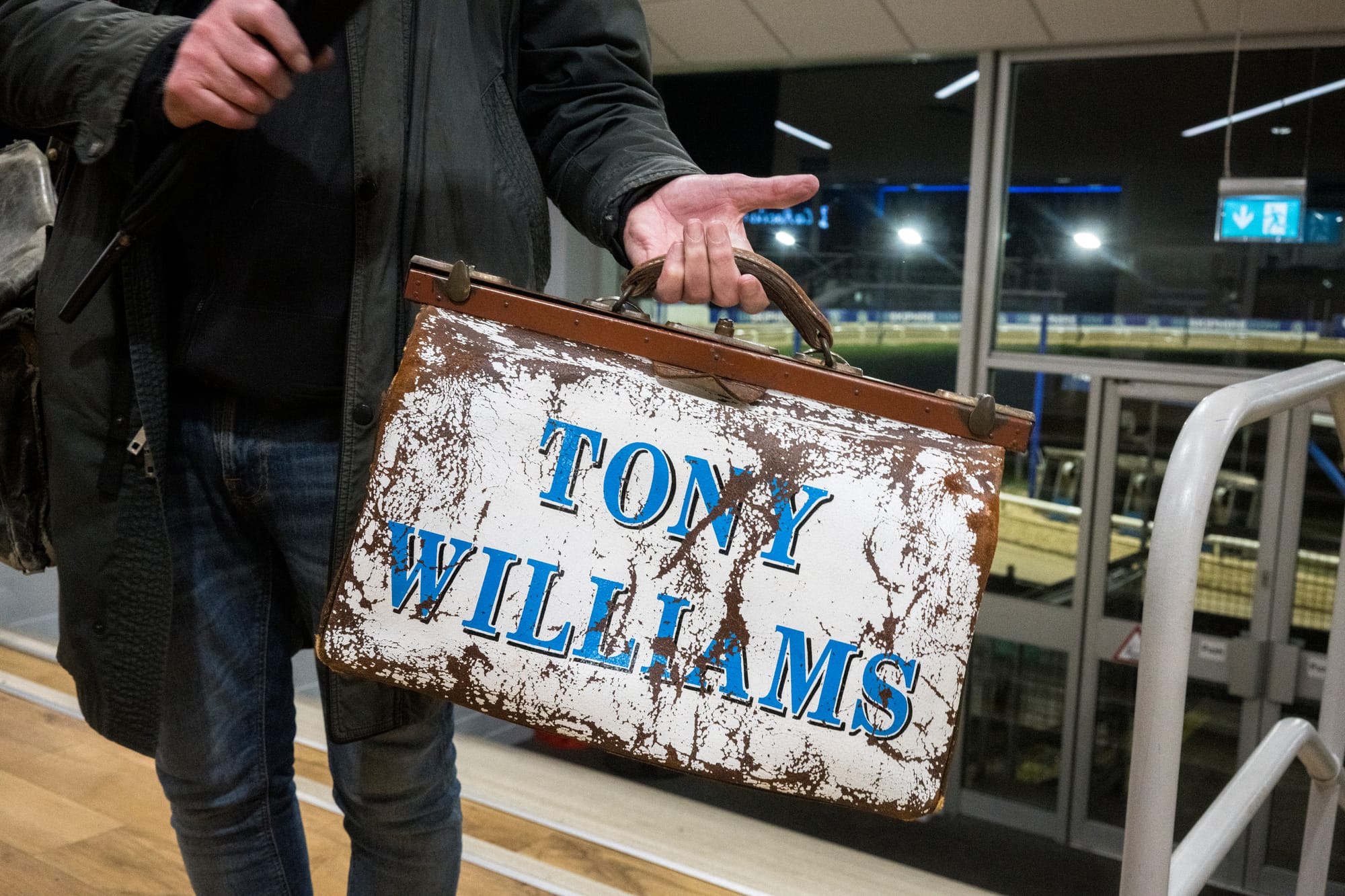

Down by the tracks, the bookies take bets just as they would have seventy years earlier, substituting a white board for chalk. Gamblers stuff folded notes inside deteriorated leather bags emblazoned with the bookies’ names: Steve Simmons, Doug Tyler, Tony Williams. People are excited. “It ain’t if you win or lose,” one man with distractingly white teeth tells me, “doesn’t matter if you’re last, as long as you’re in the race.” When I finally ask, he explains that he inherited a set of dentures from his uncle who died six months ago. “They fucking fit!” he proclaims, triumphant.

Barring one person who refuses to speak to me in case I write about animal welfare standards, everyone is excited to chat and reminisce. The news of Crayford’s closure has been taken as a grim harbinger, and people are holding on, however precariously, to a part of themselves. Inside, I find Disco Dave and Paul Young squinting over a programme. “Sad is the wrong word,” Young says of Crayford, “but this game does matter, and it’s just one more and you don’t know what the future of it is.”

Young looks back, somewhat wistfully, to the days when tracks held a “different sort of community,” one with sixteen bookmakers instead of three, when people were more interested in the dogs themselves, perhaps carrying a copy of the Greyhound Star under their arm. But times have changed. “There’s nothing wrong with it,” he says, “it’s just different, that’s all… but everything in life is different now.” By the final race, betting stubs lie torn and scattered like fallen leaves on the concrete. As the animals round the bend, transforming, temporarily, into money, onlookers leave their bodies and race with them.

If you enjoyed today's edition, please forward it to friends and encourage them to join our mailing list.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.