Hello and welcome to The Londoner, a brand-new magazine all about the capital. Sign up to our mailing list to get two completely free editions every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Happy Saturday — we hope you're enjoying your weekend. If you want to keep the heating (and lights) on at Londoner HQ, consider becoming a paying supporter of The Londoner. We're on a mission to hold the powerful to account, and for that we need our independence. As a result, we aren't backed by billionaires or private equity firms. But it's means it's only through reader subscriptions, from people exactly like you, that we can continue to do this work.

At the moment, we have 1,069 incredible paying members. By the end of this month, we'd like to be at 1,100. Can you help us get over the line? Becoming a supporter gives you access to all of the members-only content in our archive, as well as putting you at the vanguard of a media revolution. So, if you think the city deserves proper journalism, consider backing us for just £4.95 a month for the first three months.

Victoria Street, on an unseasonably warm and oppressively grey Wednesday afternoon. Bustling office workers pick their way past dozens of homeless people scattered across the promenade. An older man is slumped next to a tattered plastic suitcase, gently clutching a canvas medical bag holding pink and blue inhalers. Building sites creep upwards, like great steel mountains swelling out of the concrete.

On his lunch break, a tall, tracksuited construction worker covered in dust leaves his building site to visit a fruit stall. “You work here, yeah? On the building site?” says Dean, a gruffly affectionate fruit seller with a crop of fading brown hair, when he realises the guy doesn’t have cash. The man nods. “Take it, take it,” he says, thrusting him some raspberries. “You can pay me next time.”

One of the last traditional fruit vendors in central London, I’d walked past Dean and his stand countless times. The barrow boys and costermongers of London’s street markets were one of the most iconic features of the city, the means by which working class Londoners would get their food in previous centuries. Curious to see how their modern day equivalents are faring, I approach Dean for an interview. But he doesn’t want to speak; “maybe later”, he says wincingly, as he hauls the last of the day’s trade into a white van. So I go looking for other sellers, any enduring fragments of the days when Oxford Circus heaved with fruit stalls.

Google offers two promising candidates: Goodge Street Fruit, outside the red tiles of Goodge Street Station; and Fresh Fruit and Veg, in an alleyway in Holborn. Both were fruit selling dynasties, run by men who had flogged oranges, bananas, strawberries to millions of Londoners over the decades.

But when I pull up on my bike outside Holborn Street in the fading November light, skirting through a scrum of taxis, I am surprised to find a stall selling cheap electronics where Adam’s stand had always been. Boxes of replica Airpods, piled atop the same wooden pallets used to sell fruit. A little put out, I cycle to Goodge Street Fruit — and find a man selling flowers on the spot where Google insists there should be fruit.

“It was just a perfect storm, really”, says Adam with a sigh, when I call the number attached to the Google listing on the latter. After taking on the stall from his uncle, who in turn inherited it from Adam’s grandfather in the 1980s, Adam was forced to close last year.

Just as post Brexit labour shortages were starting to bite, the pandemic disrupted international supply chains, and made it even harder for growers to recruit workers to the UK. Surging energy prices were another blow. One of the cascading knock-on effects of events like Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was to make energy intensive fruits — like strawberries — even costlier to produce, eating into the meagre margins on which London fruit stalls survive.

Remote working lessened the need for many to travel into central London — in July 2022, London Assembly data put footfall in central London at 45% less than before the pandemic — and supermarkets were frequented more than ever. A fruit stall in central London ceased to be viable. Adam does office deliveries now. Joe, the owner of Goodge Street Fruit, sometimes sells coffee at the spot his family traded on for decades; the margins are higher.

46 million apples, 20,000 paper bags and a vanished wholesale market

Pinpointing the heyday of London street trading is tough, more of an art form than a science. One indication is the lively image of costermongers and barrow boys painted by journalist Henry Mayhew in the mid 1800s, amidst the thrumming chaos of Covent Garden Market. While many of the donkey barrows were adorned in the standard cotton and string of the time, Mayhew wrote that “some few of the barrows make a magnificent exception, and are gay with bright brass; while one of the donkeys may be seen dressed in a suit of old plated carriage-harness”. If you’re wondering how many bushels of apples were sold on the streets of London in 1851, Henry’s answer is 377,500, equating to roughly 46 million apples. Recent Irish emigres were particularly skilled salesmen, Mayhew reported, “as they have such tongue”.

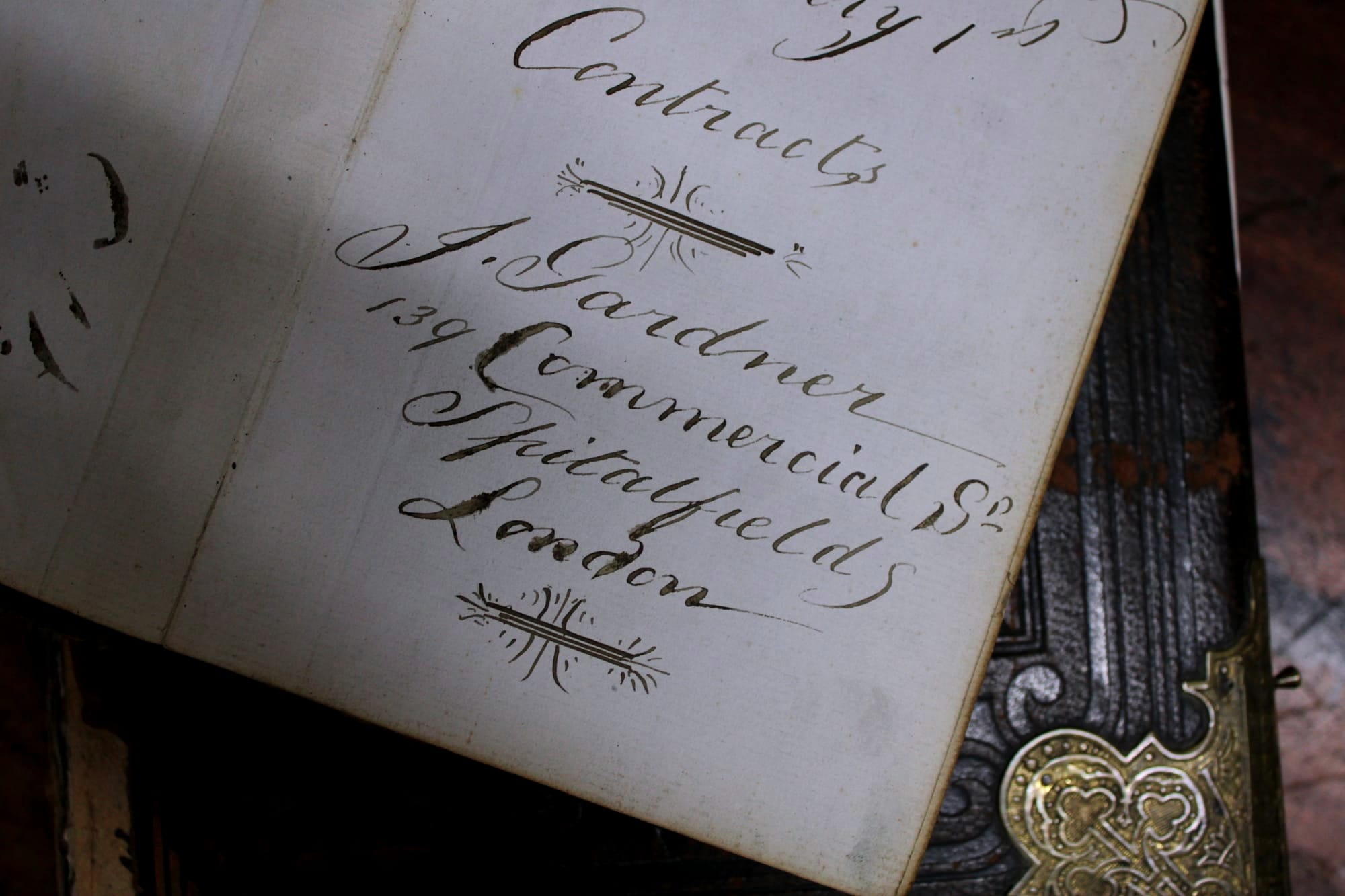

Other businesses emerged to support the barrow boy boom. One was paper bag seller James Gardner who, from his green-tiled shop in Spitalfields, began supplying the blooming numbers of fruit sellers around Spitalfields market in the 1870s. Improbably, James’ great-grandson, Paul — a genial man of around 70, with flowing grey hair and a labourer’s forearms — is still in the business of selling paper bags, the fourth generation in his family to do so. He was still trading ten doors down from James’ original shop until 2020, even surviving the closure of the wholesale market at Spitalfields in 1991. Yet mounting rental costs and council fees eventually forced him east.

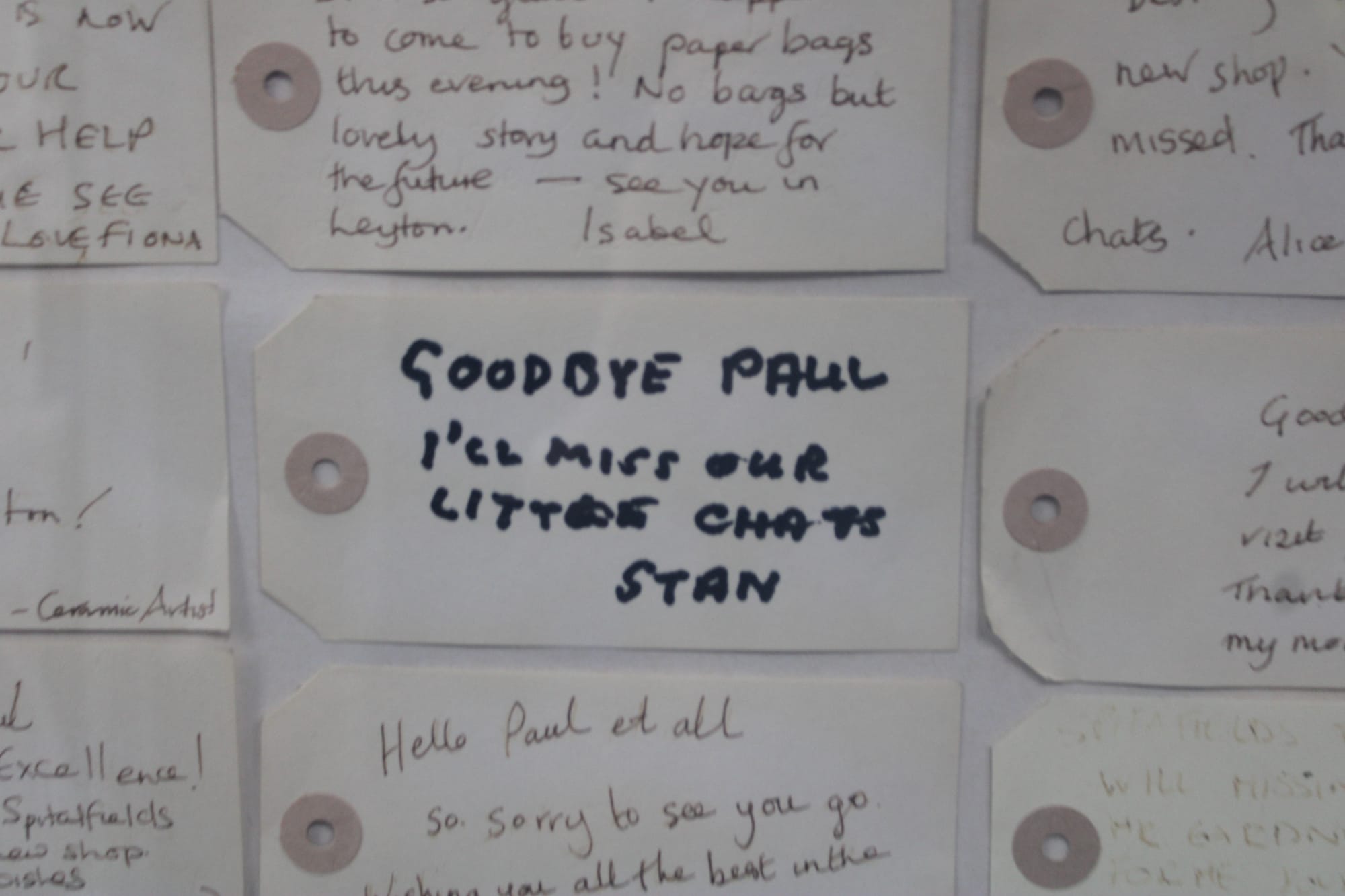

To get a sense of the more hidden impacts from the decline of London’s fruit vendors, I pedal over to Paul’s new shop in Leyton, Gardners Market Sundriesman. 90% of his business was once greengrocers’, he tells me, surrounded by piles of boxes and relics of a bygone era. His great grandfather’s record book from 1892 is perched high on the shelf behind him, overlooking a framed set of farewell cards from when he was forced out of his shop in Spitalfields. In a pre-supermarket time, Paul’s shop, described by the anonymous London writer The Gentle Author as “the centre of the universe”, supplied an entire ecosystem of the city’s independent vendors. Many remain loyal customers to this day, weathering the added distance of travelling to Leyton to deal with someone trustworthy. “I feel too guilty about ripping people off”, he says simply, after disparaging at how Amazon charges over double his rates for strip paper bags.

The forces behind Adam and Joe’s stall closures forced Paul to diversify. He now shifts around 20,000 paper bags a week, many of which go to Brick Lane Beigel shop, down from 100,000 in the 1970s. To make up the shortfall, he transitioned towards selling polythene bags and stickers to a more African clientele, who he says now make up around 80% of his customer base — and favour a similarly familial approach to doing business.

'People'll always come back'

“Paper bags!” Dean exclaims, when I returned to his stall a few days later to mention my conversation with Paul, wheeling around to pluck one from his cart. “We was the last in Church Street Market to still do them”, he said, elaborating that despite how expensive the bags are now, it’s about maintaining standards. I’d caught him at the end of a long day before, and now, on a sodden Friday afternoon, he is happier to tell his story.

Having owned the stall since 1995, Dean runs it with twin brother Tony and a familiar crew of old timers. Mick Szilágyi, a broad-shouldered, avuncular man in his 60s, wearing a green bomber jacket, says he’s been trading there since 1977. His family fled Hungary after the failed popular revolution against the Soviet Empire in 1956, arriving in London for refuge. “He’s a Hungarian Cockney”, laughs Dean. “Bet you’ve never seen that before, have ya?”

Mick has been on Victoria Street longer than some of the buildings, and from their stall they’ve watched London evolve. “I mean, a prime example is Oxford Street”, Dean says, slightly exasperated. “There was loads of stalls on Oxford Circus; from the top of Marble Arch to Oxford Circus, all of them was fruit and veg, all of them. Now, blimey, is there one fruit left?” They’ve been replaced by hot food venues with higher margins — coffee stalls and bakeries on which it’s easier to make a living.

So how have they managed to survive? “We’re very good at what we do”, he says bluntly. “You need to buy cheap and you need to get on with your customers. That’s pretty much everything. If you give people value for money and you can talk to people, they’ll always come back.”

As if to demonstrate Dean’s point about relationships, a diverse crowd of regulars drops in over the course of our conversation: an elegant Asian woman wearing a gold and red shawl, to whom Dean cries out “Mami! Mami, my dear, how are ya?”; a postman picking up bananas at the end of his shift; an immaculately dressed older couple, the man wearing a bowler hat, enquiring earnestly about the provenance of the blueberries (Peru).

A lot of the reasons for the decline of London’s fruit stalls are accidental, unfortunate consequences of a changing city. But almost everyone I speak to reserves some venom for the supermarkets. Not only have they replaced traditional stalls as places where people do their shopping, but they’ve also aggressively locked growers into unsustainable agreements, weakening the entire industry. The campaign group Get Fair About Farming found last year that 49% of British fruit and veg farmers fear they will go out of business within 12 months, with 75% of those identifying supermarket behaviour as a leading factor.

Sorry to interrupt — we promise we'll be quick. We just wanted to take you on a quick behind-the-scenes of what we do. Investigations, like the one you're now reading, take old-fashioned, boots-on-the-ground journalism. We go to places, meet people and pore over sources and reports. But this sort of in-depth journalism doesn't come cheap — especially when you're dealing with legal threats levied by some of the most powerful people in the capital. That's why a lot of media companies have given up on it, instead churning out clickbait articles that have little connection to London or those who live here. But we believe people are still willing to pay for meticulously researched, properly reported work.

Already, just over 1,000 of you have signed up as paying members to prove us right. But now we have a big target: 1,500 members. We've made it easy too: with our new member discount, a Londoner membership is just £1.25 a week. That's less than a daily coffee.

We aren't funded by billionaire oligarchs or huge companies. And that means we need the people of London and beyond. If you like what we're doing, please consider supporting us.

Another recent-ish difficulty to contend with is the congestion charge, which costs drivers £15 between 7am — 6pm on weekdays and midday — 6pm on the weekends. As a result, most wholesale markets now take place in the dead of night. New Covent Garden Market, tucked beneath a forest of glittering skyscrapers beside Battersea Power Station, opens at midnight for buyers like Dean.

It’s a gruelling way in which to make a living. Whereas 50 years ago, profits were better and there was a lively social scene among the sellers, it strikes me that it’s now not exactly something you do for the money or the lifestyle. I ask Dean if he is surprised that, of all the traders, he should be one of the last ones standing.

“You can do anything in life with a good teacher, can’t you?” he replies. “Whatever you do, whether you’re a craftsman, a historian — it’s everything.” Dean’s teacher was his dad, Harry. He had a stall on Church Street in the early 1970s, before allowing Dean and twin brother Tony to take it over when they were 19.

“There’s no one better than him”, says Dean. Throughout our conversation, he talks quickly and coarsely, in rapid bursts honed to cut through the racket of the street. But his tone softens when I ask about his Dad. “He was just good. He knew the value of stuff. He knew what he could make of it. He was always very…” he says, before trailing off. “If he said something he’d do it” he says strongly. “Trust is everything.”

Leaving Dean and Mick to carry on, I walk back up the street towards Westminster. The older man with the suitcase is there again. He’s called John, and tells me how he used to work in Harrods down the road in Knightsbridge, before a lifetime of hard luck and poor health wound him up here, watching the city go by from the street. I ask if he knows the fruit stall guys. “I know those guys, yeah”, he says thoughtfully, twiddling a cigarette filter between stained fingers. “They’re good people.”

If you enjoyed this piece and want to be sent more in-depth investigations and features, why not join up as a Londoner member today? This means you'll get weekend long reads like our piece profiling the capital's early birds commuters and Monday briefings like our deep-dive into whether London has a slum landlord problem delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Londoner and reach over 20,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below