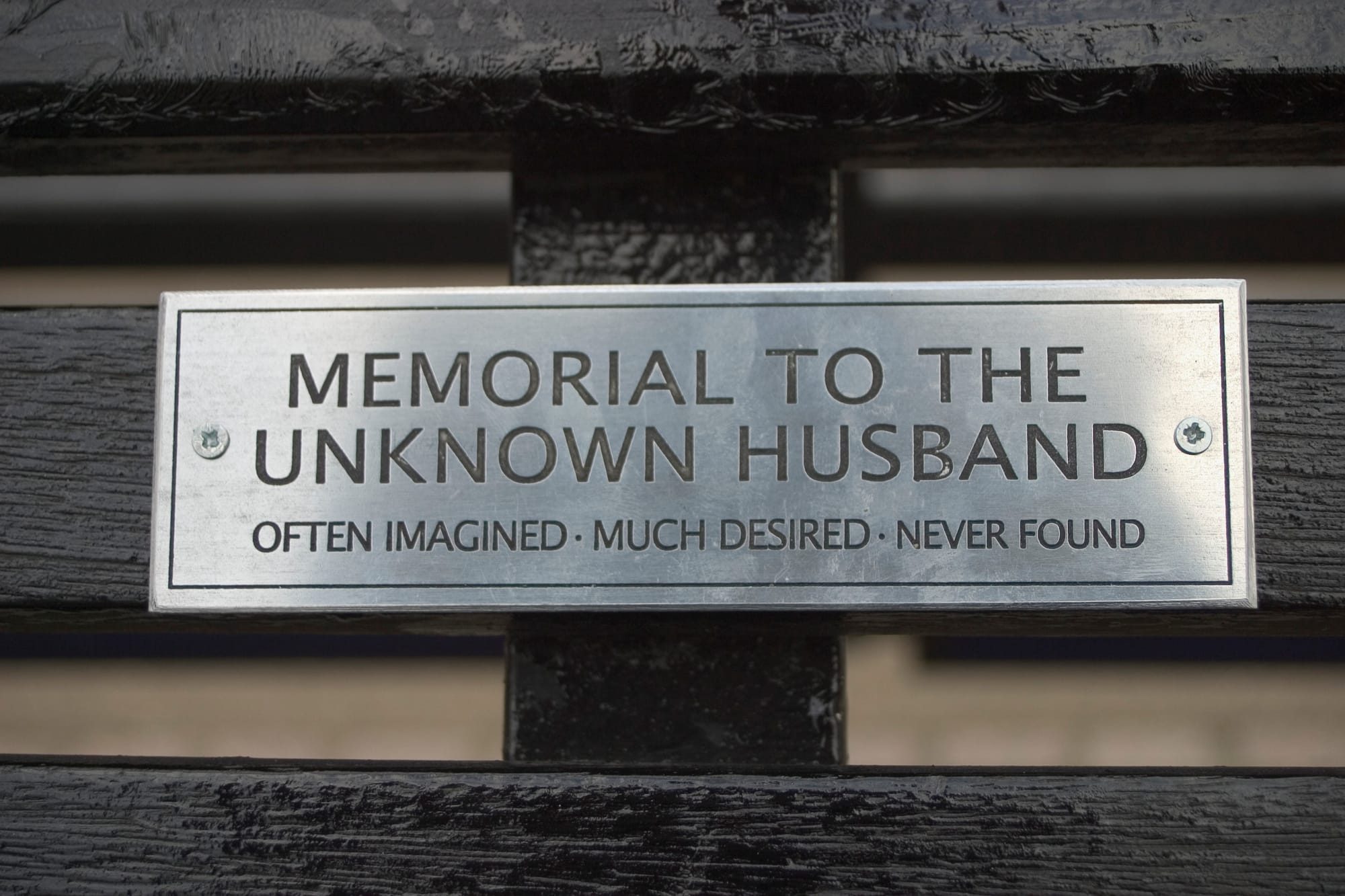

The memory is opaque, as memories tend to be. A public bench on the South Bank; spring 2006, or could it have been summer? A warm day, possibly, because the image in my mind is bathed in sunlight. Behind me is the River Thames, and in front of me, somewhere between the London Eye and the Southbank Centre, is the memorial plaque that will come to obsess me for the next 20 years.

It reads:

Memorial to the Unknown Husband

Often Imagined. Much Desired. Never Found.

I remember being struck by this extraordinary public expression, not by a bereaved person for someone they loved and lost, but for someone who had never existed. The haunting cadence and heartache in those 11 words reminded me of what is often described as the saddest short story ever written, often apocryphally attributed to Hemingway, “For sale: baby shoes, never worn.”

What could have driven someone to write something like this? Public bench dedications in a central London spot can cost upwards of £2,000, not to mention the prospect of council bureaucracy and a lengthy waiting list for installation. I imagined an elderly woman at the end of her life, looking back at the arcs and troughs that formed her many years, and seeing a void where the love of her life should have been. The desire to hear her story first hand instantly preoccupied me.

This was the mid-noughties; the internet was still in its infancy. My first port of call was Lambeth council, who I understood at the time to have oversight for public benches in the area. But they failed to answer the phone, or respond to emails or messages left on the department’s answerphone. The mystery seemed unsolvable. But it never left my mind. Every few years, I would search for information on the plaque online and, each time, I’d get a little bit more back. Mainly, what I found was others who were fascinated by it.

“Seeing it for the first time, questions trouble the mind: who would go to such effort (and expense)? What must be their backstory? At what age did they decide to commemorate something that had never actually happened?” wrote Stephen Emms in 2012, as part of his column on public benches for Time Out magazine. “We’ll probably never know (and, believe me, I’ve asked around)."

Memorial to the Unknown Husband appeared on Open Benches, a site dedicated to tracking notable memorial benches around the world, and in several articles, including one from the BBC in 2022. Clearly, the plaque’s inscription had struck a chord with others. But no one had found out the one thing I wanted to know: who did this? Then, late last year, it finally happened. I found her.

Hello, The Londoner editor Hannah here. Enjoy uncovering the capital's hidden stories? We have plenty more where that came from — for me, there's nothing better than digging deep into fascinating tales about the city that are never usually told. Of course, that's alongside our incredible scoops, long-form investigations and buzzy dispatches.

If that sounds up your street, sign up to our mailing list to get two completely free editions of The Londoner every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No fluff, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

'That could have been me'

Memorial benches began to appear on the streets of London during the Victorian era, as an increasing number of parks and green spaces were established within ever-more urbanised cities. The high mortality rate of the time, especially amongst children, was changing the place mourning had in public society, and benches were part of what historians refer to as the “beautification of death” movement, in which symbols of death that commonly featured on gravestones — an hourglass with time running out, cross bones — were replaced with sentiments of love and hope.

Today, London has tens of thousands of memorial benches. Many boroughs have lengthy waiting lists for a new dedication; Hampstead closed its waiting list in 2018 due to excessive demand for benches on the Heath. “A public bench means freedom,” wrote Tom Hodgkinson, in an article about their place in London life. “Benches are romantic, anonymous zones. We imagine spies meeting on them, and lovers. They are refuges.”

Anne Karpf, an academic and journalist, became interested in public benches when her husband had a hip replacement, and she realised how important it was to have somewhere public to sit. Her thesis, published this year, is called She Loved This Place, and Karpf was so struck by Memorial to the Unknown Husband that she included it.

“When I first saw it probably about eight, nine years ago, there was a little part of me that thought ‘that could have been me’,” she tells me over a video chat one morning. “I thought, ‘there was a woman who has surveyed her life and has got past the mourning of whatever she might or might not have had, and could view it humorously’.” Unlike me and others, Karpf did not think the plaque’s words were inherently bathetic. “I gave a lecture on the subject of public benches in 2019,” says Karpf. “When I flashed it up on the screen, everyone just kind of collapsed laughing. Everyone thought it was just adorable… I felt that she was speaking for a lot of women.”

The bench disappears

London’s South Bank was once a marshy riverfront, surrounded by tanneries, factories and breweries. After heavy bombing during world war two decimated this local industry, its regeneration — marked by the 1951 Festival of Britain — transformed into the cultural hub it is today. Tourists pose for selfies by the Thames, runners dash along the riverfront, couples stroll hand in hand.

Did any of them notice when, one afternoon in the early winter months of 2006, a tall man armed with a screwdriver began to attach a metal plaque onto a bench? Did they notice the woman at his side, nervously keeping watch? Did they overhear him explain to her, “If you screw it far enough in, they won’t be able to remove it”? Possibly, though no one intervened or asked what they were up to. The pair took a few surreptitious photographs, then vanished into the city.

And there the plaque remained, drawing second glances and laughter from passers by for several years. Until one day, when it disappeared — along with the entire bench. No one knows exactly when or where the plaque may have ended up. When I approached Lambeth council in the latter half of last year to find out, I finally received a response, but was told the location of the bench (76 South Bank) meant it was likely managed by the South Bank’s Business Improvement District. They tried their best to find out what happened to it, but with little info to go on — “it is a bit niche” — were only able to direct me to an organisation called Coin Street Community Builders, a social enterprise that regenerates the area of the South Bank where the bench was.

Their helpful media manager offered to “put the feelers out.” No one on his team remembered the bench or the plaque, but he told me benches tend to get replaced or repaired every five years or so as a matter of course, and that a new bench is now at the site there. “I was so intrigued by your story,” he said, “I wish I could have found out more.”

Meeting the Easter Bunny

“I feel a bit sad for you that you have met the Easter Bunny, have met the person, because now the mystery is solved, and you're just gonna close that chapter.” It is nearing the end of 2025, and I am speaking over Zoom to Elizabeth Croft, a 50-something-year-old woman with a northern accent softened by years abroad. She is sitting at her kitchen table in Stavanger when we speak, a peninsula on the southwest coast of Norway, where she has lived for nearly 20 years.

The story begins, Croft says, when she was 28. Her life looked to be all sewn up: raised in Cheshire, she’d studied humanities at Bradford University, before moving south, finding a job in marketing, and getting engaged. And yet the pieces didn’t quite fit. Croft found her job soulless: “I wasn’t doing what I wanted to do”. Then her fiance called off the wedding. Bit by bit, the life she had constructed came apart.

“At the time, that break up was horrendous. To stop that train once it had started was really, really hard. But it was all just a bit like the Game of Life, you know; we were going to get married, we were going to get the car, we were going to have the kids. It wasn’t long until I realised that, actually, if I had gone down that path it wouldn’t have been happily ever after. ”

The broken engagement was a catalytic event. Croft left her marketing job and enrolled in an art foundation course in Brighton. When that was over, she got into Goldsmiths School of Art, and in 2003, Croft travelled to Burning Man festival. She went on her own and volunteered to help out with the Lamplighters, the crew who go around the festival lighting up the desert village every night. Burning Man was started by two men who burnt an effigy to mark the end of a relationship, she explains, “to cleanse the relationship, and pack it away, and say ‘now it’s over’”, and evolved to include “a huge temple, to honour and release those who were lost, with an emphasis on suicide.” When the effigy burns, Croft says, the place goes crazy, “there’s noise, they party, it’s mad.” When the temple burns, the desert is silent. “At its heart, Burning Man is about letting go.” Croft would return to the festival again and again. But back in London, an idea was forming.

If you're enjoying this piece and want to be sent more in-depth investigations and features, why not join up as a Londoner member today? This means you'll get weekend long reads like our piece on the enduring appeal of the Regency Cafe and Monday briefings like our update on the penguins trapped beneath the South Bank delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.

“In the beginning, it was a stone,” says Croft, as well as more words. Her former fiancee was only part of the motivation for the work, says Croft. It was also the strange place of women in British society at the time, one which elevated both a kind of laddish post-feminism but also Bridget Jones, as well as an obsession with singletons. In the end, stone proved to be too heavy. The words got whittled down: “Memorial to the unknown husband. Much Imagined, often desired, never found.” The plaque was born.

Croft used the printing room at Goldsmiths to etch the lines into metal. She remembers being happy with how it turned out. Less so with how it was received by her coursemates and tutor. “The tutor thought it was ridiculous that I was making work about being single, but why? Tracey Emin’s work is about being single and being left and having an abortion. Sarah Lucas's work is about the objectification of women.”

Her coursemates “started talking about post-feminism and I was sort of saying, the only time you can talk about post-feminism is when we have equality. I was a mature student, asking what does it mean to be single at 33? But the younger people didn't get it.” Afterwards, she remembers speaking with a female tutor who she admired, who told her “there’s some part of you that you’re hiding”, and to think about why she was drawn to Burning Man, a place Croft said at the time was about “outsider art.” “She sort of encouraged me to make something public, I think.”

Croft considered a few public places, but settled on the South Bank because “it’s a place of leisure, it's romantic, couples promenade there”. But also, “it’s where the IBM building was and I knew my ex had started working there.” Then she asked a fellow student, in the year above her and originally from Norway, to come with her, “for protection and safety in numbers, since it was a kind of guerrilla action and women on their own often got hassled in public.” And in a twist I could not have predicted, she tells me that man would go on to become her husband.

'It sticks with you'

In the end, finding Croft was simple; she’d added her details to an online site about public benches where her plaque had featured. We went about arranging to speak but were delayed by domestic drama, travel, life. “How’s this for irony: for a woman who made a plaque to her unknown husband, I am currently going through a divorce,” Croft says.

When we do eventually talk, it is the first time Croft has thought properly about the plaque for many years. “It sticks with you,” she says of the broken engagement, “because you imagined a life together and it didn’t happen.” But it is one of many sliding doors moments of Croft’s life, and “as you get older, you think more about the parallel version of you” who made different decisions and ended up on a different path.

Before moving to Norway, “I would go and sit on a bench nearby to watch people’s reactions.” She was surprised, even hurt, by the number of people who laughed at it. How does it feel to know at least one person has spent two decades trying to find her? “The fact that I've made something that stuck with somebody for so long is just kind of mind blowing to me.”

I tell her about my attempt to solve the mystery of the plaque after its removal, about which she is sanguine. The plaque’s purpose has been served, wherever it ended up. For now, Croft is living presently, raising her child and working happily in the arts in Norway. “I read recently that to be a fully formed adult is to hold grief in one hand and hope in the other, and to be stretched large by them,” she tells me, reflectively. “The older you get, the more grief you're carrying, and maybe the less hope you have. I was definitely full of hope when I was younger.”

Correction: This article has been amended to show the correct date that the author spoke to Elizabeth Croft.