Hello and welcome to The Londoner, a brand-new magazine all about the capital. Sign up to our mailing list to get two completely free editions every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Happy Saturday to our lovely readers. Having a good weekend so far? Here's one way you could make ours even better: by becoming a paying supporter of The Londoner. We aren't backed by billionaires or private equity firms (as much as that might make things easier, we're fiercely devoted to our independence and integrity). That means it's only through reader subscriptions, from people exactly like you, that we can continue to exist.

That's why we set ourselves the rather ambitious target of reaching 1,000 subscribers by our one year anniversary (tomorrow). After a tidal wave of support from you all since we set the lofty goal last week, we're now just 10 members away, but we need your help to get over the line. If you think London deserves quality coverage — if you think you deserve quality coverage — consider backing us for just £4.95 a month for the first three months. Becoming a supporter gives you access to all of the members-only content in our archive, as well as putting you at the vanguard of a media revolution. Let's do this together.

It came from the sewer. Or, more accurately, it probably came from a ditch, or a cesspit. It isn’t particularly intricate: simply a plate, average sized, with a shallow well. The glaze is off-white, the colour of tallow or bone or parchment, and the text is clear-sky blue; all typical for Delftware of this kind. All in all, it’s technically unremarkable, as far as 17th century pottery goes. What is remarkable is its inscription: “You & I are Earth / 1661”.

I can’t remember where I first heard about the plate, though I’ve been aware of it now for a long time. I even went to see it at the old Museum of London site at London Wall (unfortunately, I’m told it won’t be on display at the institution’s new Smithfield site). There’s an undeniable poignancy to it: the uneven intimacy of the “You & I”, as if the subjects are edging closer together; the grandiose finality of the “Earth” and its curlicued “E”. There’s something, too, about the direct address that draws you into its confidence, a secret whispered into your ear. Put simply, it is desperately romantic: you will die, you are already dead, and here I am with you.

I am not the only one affected by it: its image has been circulating around the web for a good two decades, at least, with Google reporting the first spike in interest around 2005, though it’s around 2016 that searches begin their sustained climb. With the advent of social media sites focused on image sharing, it spread around the internet — posts regularly fetch tens of thousands of likes on platforms like Instagram or Reddit pages such as /r/artefactporn. When I spoke to Ashton Bainbridge, the PR manager at the Museum of London, where the plate is kept, she told me that she couldn’t think of anything else in the collection that elicits this kind of impact. When I posted on social media that I was writing about the plate, friends were effusive (sample: “I would die for this plate”, “I wanted this engraved inside my wife’s wedding ring”).

But more conclusive than its social media cachet is the real world evidence for its popularity — fitting, for something that so explicitly references its own tangibility. People feel so deeply about the plate that they’ve got tattoos of it, replicated it on knitwear and named their albums after it. It’s been a source of inspiration for paintings, literary journals and UCL Media BA shows. It’s even made its way into high fashion, emblazoned on a $820 jumper from SS Daley and immortalised in a miniature resin replica on the front of a $575 handbag by US brand Puppets & Puppets. Sophie, who owns one of the bags, tells me that she was inspired to buy it after seeing “a gorgeous and chic woman at a party wearing [one]”. She had no idea about the plate beforehand, but now has an appreciation for it — and says that the bag was “a great investment. I wear it all the time”. But how, when and, more intriguingly, why did this lead a seemingly ordinary, anonymously made plate to become a cult classic, a high-fashion inspiration and a global internet sensation?

Seeking facts, I turn to Hazel Forsyth, who as senior curator at the Museum of London is well-acquainted with the plate. Having no presence on social media, she was oblivious of the plate’s popularity, she tells me on a video call, folding her hands as she speaks. Her brown hair is short, her rectangular glasses thickly framed, and her turtleneck is the colour of cobalt oxide. “Every now and again, it's featured when we've done exhibitions, or I've published it myself, when I've been doing something on the plague, for example. But I had no idea that it had attracted this kind of interest until your email…”

Even for the experts researching it, the facts of the plate’s story are bare-bones. We have “absolutely no idea” how it came into the collection, Hazel says bluntly, other than it was purchased in the late 19th/early 20th century. “Huge amounts of material came into our collection as chance finds recovered from building sites in London. And I suspect this is one of those.” What’s more interesting, though, is the fact that it’s survived at all, and in its relatively pristine condition: “tin glaze is a lead clay to which tin is added, and the tin pacifies and creates that white surface, but it's very brittle — it chips very badly. And if it was [found in] a sort of cesspit, the likelihood is that you'd get all sorts of chemical reactions with the material of glaze, some kind of iridescence or changing colour.”

We can hazard a confident guess at a few things: that it was commissioned for a middle-class household, that it was created at one of the many Delftware factories on the South Bank, that it chucked as rubbish into a “dry-ish” kind of cesspit. But other than this, everything is conjecture. “The typical thing was for London householders to remove their rubbish and then drop it into a neighbouring cesspit. And it may be that somebody was moving into the property, someone had died, and they were chucking out all their stuff. It could have had a relatively short lifespan, but it could have been something that was kept for a long time before it was finally thrown away. None of us will ever know.”

To Hazel, the plate is just one part of a corpus of post-mediaeval objects she works with, an example of the era’s vogue for the memento mori: a reminder that your life on earth is fleeting and that you, too, will die. “It is part of a sort of collection of ceramics that were inscribed in some form or another, either with some sort of moral maxim or some souvenir… It's the same sort of time, too, that you get lots of posy rings or posy inscriptions and there are lots of analogous inscriptions on ceramics, things like ‘When you see this, remember me’, ‘remember thy end’.”

Alongside the religiosity of the memento mori — Hazel says that to a person in the 17th century, the object would’ve “certainly” been read as a Christian instruction that “made people think about their faith and their relationship to God” — these objects were created at a time in London’s history when death was pervasive, no matter one’s wealth or social rank, stalking dank beggars’ alleys and gilded royal courts. Though the Great Plague of 1665 was the last major outbreak in England (and, aside from the Black Death, the most infamous, with experts now estimating it killed around 100,000 people), the plague was endemic, a near-routine part of life, alongside ague, dropsy, consumption, rickets, bloudy flux, imposturne. Whoever owned the plate in 1661, it’s likely that they would have known somebody whose children had died or who had died in childbirth, or who had died from one of the myriad illnesses and diseases that could fell even a young person in the rudest of health. It’s likely, too, that they would’ve thought about this, about why those people were taken, about why they had not been, about when that day would come.

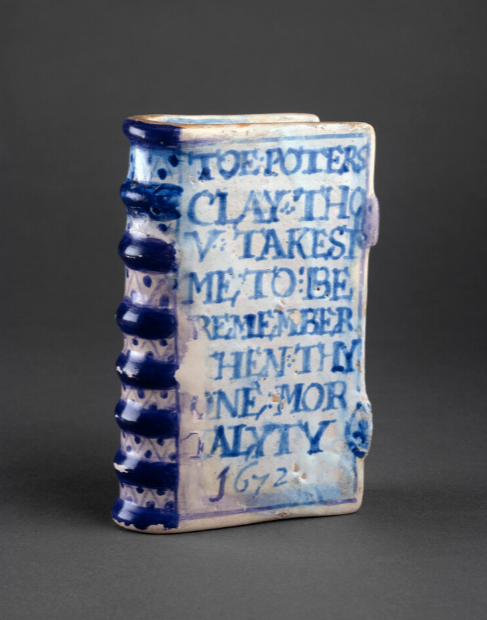

It is intriguing that it has become so much more famous than similar objects, such as the aesthetically comparable “Weilcom my Freinds / 1661” plate, or a 1672 hand warmer in the shape of a book with the relatively close inscription of “Toe poters clay thou takest me to be / remember then thy one mortalyty / Earth I am it is most trew / Disdain me not for soe are you”. Perhaps it’s the succinctness of the “You & I” message that lend it impact. Unlike the other two examples mentioned, it’s short enough to not contain any archaic spellings and to make immediate sense. The tone, too, is different: a loving and tender promise of and a plea for eternal togetherness. It functions as a shard of found poetry, the early modern equivalent of a Sappho fragment. The others, with their everyday calls to friends or long-winded, strangely pugilistic sentiments about “disdain”, lack the star-cross’d romanticism.

There’s a poignancy, too, in the anonymity of the piece. Severed from its original, now unknowable context, we can project our own meanings onto it, imbue it with our own stories. It’s this quality that attracted Camila Lim-Hing, an NYC-based ceramic artist who first saw the plate on an archaeological page on Instagram and ended up getting it tattooed on her hand (later getting “Weilcom my friends” on the other). Over email, she tells me that neither the Museum of London’s blurb — “The inscription is a reminder of man's mortality” — nor a Reddit post “suggesting it may be a biblical reference” feel particularly right for her: “There’s no other information on the artist and their intentions... I like to think it was just a little guy in 1661 reveling in the love for his friends.”

If you enjoyed this piece and want to be sent more in-depth reads on rarely-seen corners of the city, why not join up as a Londoner member today? This means you'll get weekend long reads like our piece profiling the capital's early birds commuters and Monday briefings like our update on our story about the penguins trapped beneath Southbank delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.

If you’d like to sponsor editions of The Londoner and reach over 20,000 readers, you can get in touch or visit our advertising page below