Because we think this is vital public-interest journalism — the kind everybody in the city should read — we've made this piece free. But this kind of work is costly, and as a small outlet dedicated to proper reporting on the capital, we can't do it without our supporters. If you value today's piece, please consider becoming a subscriber of The Londoner so that we can continue to do more of this work in future (and right now, new members take 50% off, making a Londoner subscription just £4.95 a month for your first three months).

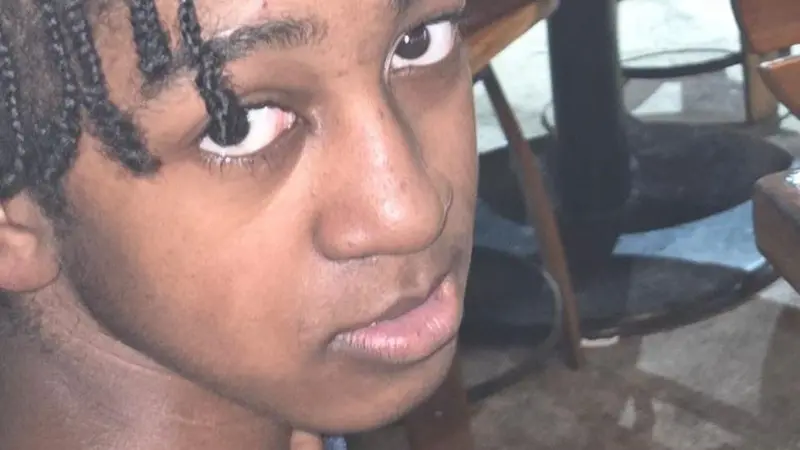

Two of Lee’s boys have been killed this year. In September, a 27-year-old former player on Lee’s youth football team was shot dead. In March, a 16 year old who attended Lee's well being drop-in group was killed by a gun at point blank range. One of those arrested for the murder is 17 years old.

It’s been more than 20 years since Lino “Lee” Dema founded the St Matthews Project to support young people in south London, including current and former gang members. In that time, ten have been killed, but “we’ve never lost two in one year before”. The data is stark: since 2019, more than one in ten London homicide victims has been a teenage black boy. The number of black victims of knife homicides is higher in recent years than it was 20 years ago. And in the last decade, homicides of black people across the capital rose.

But how does this square with the fact that, on some key measures, London is indisputably safer than ever? Despite a widely held perception of the city as dangerous — with US President Donald Trump claiming that “crime in London is through the roof” — murder is at a record low. Sadiq Khan is proud of this statistic, telling the Labour party conference: “At a time when politicians and pundits are talking down our city, I think it's really important we talk up our city based upon the evidence. The evidence is violent crime with injuries down in every single borough across our great city.”

So what’s behind this fall? And if that’s the case, why isn’t the change being felt equally — why aren’t boys like the ones in Lee’s youth projects any safer?

How was the decrease in the murder rate achieved?

In the 12 months to September 2025, there were 95 victims of homicide recorded by the Metropolitan Police Service (excluding those recorded by the British Transport Police, and the square mile of the City of London). That’s a 13% decrease on the previous year, and less than half the number seen this time 20 years ago.

Fraser Nelson, a journalist at The Times, has written extensively about this trend. While there are sometimes issues with how crime data is collected, he used different statistics to show that it’s genuine: his work shows that there were 790 admissions to London hospitals for assault by a “sharp object” in the year to July 2025, an 11% annual decrease.

What accounts for the current historic low? In a press release, Sadiq Khan claims it is thanks to “our record investment and intelligence-led enforcement by the Met, vital prevention work led by my Violence Reduction Unit and our pioneering efforts to tackle reoffending.”

Junior Smart, who founded St. Giles Trust’s SOS+ and has received an OBE for services to youth intervention, gives credit to the mayor’s Violence Reduction Unit (VRU), which funds prevention and early intervention across the city, including small grassroots projects. He also cites the work done by the VRU in more than a dozen London boroughs to try and reduce school exclusions, which are shown to increase the likelihood of a child’s involvement with violence.

James Alexander, an academic in the criminology department of London Metropolitan University who leads the evaluation of multiple local authority youth safety projects, agrees: “We're getting better at doing some stuff really early, because if you get it right in those years, you can have less angry teenagers.” But he cautions against merely patting ourselves on the back and resting on our laurels. “We've seen these kinds of trends before, and it's gone back up. Statistics can change very quickly — around 2012 we saw a decline, and then it rose very quickly again.”

Alexander, who is also a St Matthews Project football coach and trustee, tells me that there's a few-year lag between policy action and the crime statistics, so the reduction we saw in the early 2010s is actually down to the increase in funding and support seen in the late 2000s. “Then you had the stripping back of the state from 2010, and then a couple of years later, that's when you see the issues increase.” Research published last year by the Institute for Fiscal Studies found that teenagers who lost access to their nearest youth club were 14% more likely to engage in criminal activity in the six years following closure, particularly theft and robbery, drug offences and violent crimes.

Lee puts it more frankly: “That last government for 14 years just trashed society as a whole, they just [ran] it into the ground. Not just youth services, but hospitals, mental health support, police stations.”

Alexander is quick to tell me that the vast majority of neighbourhoods in London are perfectly safe, and that these crimes occur in “small pockets of poverty and deprivation”. Still, he adds, in areas where those issues are on the rise, “we should be concerned”.

Who gets left behind?

The day I speak to Smart, news has just broken of a 15 year old stabbed by death in Islington, later named as Adam Henry. A 20 and 22 year old have been charged with the murder. “Yes, overall numbers are falling, but if you stand in certain postcodes or talk to certain families, it doesn't feel like a success story,” Smart says. “Try saying that to the family of that young boy who was murdered.”

But for all the good work being done, the results are not being seen equally. The reduction in homicides has primarily been driven by a decrease in white victims, which have fallen by two-thirds in 20 years: from 95 in 2004, to 32 in 2024. In 2004, half of London’s homicides were of white people; now, they account for less than 30%.

In the same period, homicides of Asian people have more than halved, but homicides of black people have only fallen by a quarter. And between 2014 and 2024, homicides of black people actually rose: from 29 to 47.

Segmenting the data by age paints a tragic picture. In 2003, the leading demographic for victims of homicide in London was white men aged 25 to 34, closely followed by black men of the same age group. But since 2019, more than one in ten London homicide victims has been a black boy aged 13 to 19.

And while the number of white people who die by stabbing has more than halved in the past two decades, the number of black victims of knife homicides in recent years is actually higher than it was 20 years ago.

The racialisation of inequality

Smart is quick to voice concerns with the painting of this as a racial issue. “If we say it's a racial problem, we amplify that cultural identity is the cause, and that is both wrong and damaging,” he explains. “This isn't a racial problem at all: this is an inequality problem that shows up along racial lines. The same patterns appear wherever you have high deprivation, low trust in institutions and limited opportunity.”

“For years we had this obsession with black-on-black crime,” he says. “But the reality is, these are children, and they deserve to be looked at properly.”

Alexander says this trend is mirrored across much of the research he does in criminal justice, because of the growing racialisation of poverty and deprivation in London. The latest census shows a clear correlation between those neighbourhoods that have a higher proportion of Black African in the population, and those that are most deprived.

And it’s also important to recognise that support is easier to access for white children than black, Alexander says. “If you're black, you're more likely to be referred to children’s mental health services after an arrest or after a social service intervention; [whereas] for white people, it would be through the doctor and through the school,” he says. “So when you look at these risk factors and the way that we're addressing those risk factors, it is unsurprising that we're struggling to reduce the victimisation of black young men, compared to white young men.”

While funding cuts to the Met in the austerity era undoubtedly had an impact on the rising homicide numbers of the late 2010s, Smart is sceptical as to the effectiveness of the Met. “In the communities that we speak to, the young people feel over-enforced and under-protected,” he says. “If you want the young people to talk to the police, they have to trust the service. And I honestly think that right now, they just don't.”

Alexander believes enforcement has a role to play, but only alongside “properly-funded” prevention programmes, as well as work to tackle the root issues of poverty and deprivation.

“You cannot arrest yourself out of this problem, because it doesn't change poverty, deprivation, not getting the right support; it doesn't change those factors,” he says. “So you take those people away and lock them up, very quickly you will have another group experiencing exactly the same situation, doing exactly the same thing.”

The future

So what needs to be done, to ensure this decline in homicides continues, and that it’s making an impact with the communities most affected?

“Previously, we've got to some points like this, and victory has been declared too early, so resources have suddenly shifted away, “ says Patrick Green, chief executive of knife crime education charity the Ben Kinsella Trust. “If history teaches us anything, now's the time to put more resources into this, because it's starting to show that it works.”

Alexander says he’s concerned about the short-term nature of funding for small, grassroots projects. He also worries that the rightful focus on prevention is eclipsing a gap in provision for those who are at crisis point already.

“We can do this preventative work, but it means that [for] those that are known to youth justice, known to gang services, we don't have the resources,” he says. “But even the preventative work is patchy and funded for two to three years at a time. And the work for those that really, really desperately need it now is even patchier.”

That’s why Lee finds it hard to celebrate the statistics that show falling homicides: he sees the reality on the ground, and the growing threats. “Every serious incident we've had over the last three years has involved a firearm,” he says. “That’s what we’re seeing at the coalface.”

In a video documentary celebrating 20 years of the St Matthews Project, former youth group participant Isaac stands on the football pitch, empty after dark, speaking to the camera about the impact the group had on his life. “Growing up, I was a bad kid. I used to fight a lot. I couldn't tell you how many times I've probably done the wrong thing.”

As he speaks, an unmarked police car flashes its blue lights, and pulls over. The officer rolls down the window, gestures at camera equipment, and asks, “What’s going on here?”

Isaac walks over, unconcerned. “We’re just filming, letting them know about the community, and the football team in the community.” He leans against the fence, points at the police vehicle. “How we’re helping young kids stay out of that car.” He laughs. “If anything, we’re doing you lot a favour.” The car drives off.