Welcome to The Londoner, a brand-new magazine all about the capital. Sign up to our mailing list to get two completely free editions of The Londoner every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

Alicia Weston shouldn’t be in parliament. She’s not a policy wonk or an executive hauled up to address some scandal. Nonetheless, on an otherwise unremarkable March afternoon, she finds herself waiting for a grilling from a committee of MPs, the last person standing against the passage of a bill that could permanently shutter a centuries-old London institution.

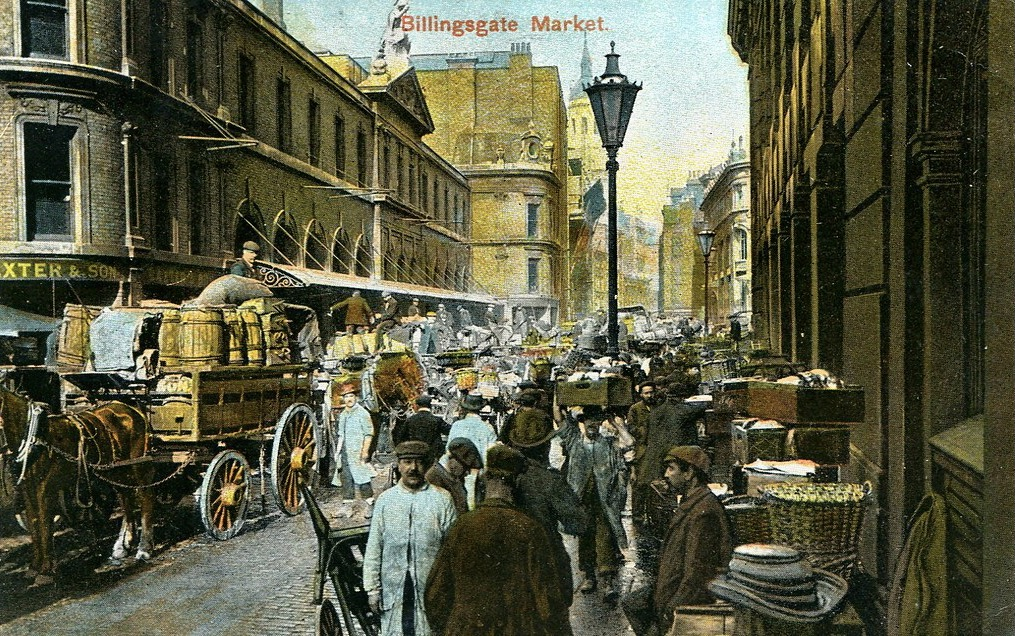

It wasn’t meant to end like this. The capital’s historic wholesale markets, Smithfield and Billingsgate — located, respectively, in Farringdon and Canary Wharf — had been set to move together to Dagenham until last November, when the City of London dropped the bombshell that spiralling costs had killed the scheme. Instead, the markets would shut without replacement in 2028.

The announcement was greeted with sentimental tributes in the Evening Standard and the national (and international) press. But there was oddly little resistance to the closing of two of the last bastions of tangible, messy labour and commerce in a city ever more sanitised for the benefit of office workers and tourists. The markets themselves seemed strangely ambivalent, remaining in lock-step with the City and communicating largely through bland joint press releases in which they said they are “confident that the Traders will continue to serve the whole of London”.

So how is it that Weston — an ex-investment banker who now runs a food poverty non-profit — and a handful of Hackney fishmongers have ended up being the only ones to fight back against the disappearance of Smithfield and Billingsgate?

Psst! Did you know you can get two totally free editions of The Londoner every week by signing up to our regular mailing list? Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

Battling the bill

Weston’s journey to parliament began in January, when she read about the Dagenham cancellation online. As soon as she heard the news, she thought of the string of local fishmongers at Ridley Road Market, near her home in Dalston: “I used to go to Billingsgate occasionally myself, because I used to run a supper club, and [I’d] see those guys there,” she tells me over the phone, her mildly posh accent spiked with righteous indignation.

Those supper clubs were the start of a journey which led Weston to found Bags of Taste, a non-profit aiming to help people on low incomes eat more affordably and healthier. Fishmongers like those on Ridley Road Market play an important role in making such choices possible, providing an eclectic range of produce to a diverse customer base at prices they can afford. But this is only possible because of their access to Billingsgate — unlike wholesalers, the market can provide this variety at low volumes, as well as allowing fishmongers to shop around for a good price and check the quality of produce. This is acknowledged by the City’s own commissioned food security report, which, while noting the long-term decline of trade at the markets, notes its important specialist role serving “those with low-volume orders that are often overlooked by larger wholesalers”.

Weston thought of how losing the market would jeopardise these businesses, as well as the food poverty outcomes that had become her life’s work. And her concern intensified when, visiting Ridley Road, she discovered the fishmongers had no idea Dagenham had been cancelled. “When I spoke to them they were nearly crying,” she recalls.

The City had said in November that it would help traders look for a new site within the M25, but this did little to soothe fears. Everybody knew how much resource had gone into the failed Dagenham project. And then there was a matter of legislation. Smithfield and Billingsgate aren’t just any old markets — their provision by the City of London, as well as their respective locations, is written into a series of Acts of Parliament going back centuries. To make big changes to the markets, the City has to put forward a private bill (pieces of legislation which serve the interests or benefit of particular people, groups or organisations and are introduced by external bodies, often local authorities, rather than the government or MPs).

The City had already brought forward a bill to enable the move to Dagenham, but this was abandoned, and, the day after announcing the planned move was cancelled, a new one was introduced into the House of Commons. The bill involved partial or wholesale repeal of 19 different pieces of legislation, going back as far as 1846. Crucially, though, it made no commitment to a replacement site for the markets.

Weston’s visit to Ridley Road came on the deadline day for petitions against the markets bill, but she nonetheless sprang into action, writing up a lengthy submission under the auspices of Bags of Taste for the fishmongers to co-sign. In doing so, she joined a handful of others challenging the bill, including one who had organised an online petition signed by tens of thousands. But the rules about who is allowed to petition against private legislation like the markets bill is strict — all were rejected out of hand.

While she had the right to appeal to a rarely convened parliamentary body called the Court of Referees, Weston knew her chances were slim. “Under the rules, there is a vanishing chance of [us] ever getting standing,” she explains. She was inclined to give up — until a call on 10 February with the City. “I decided to fight because I was extremely cross with the City of London Corporation and the way they approached me.”

The call was with a City of London lawyer and a consultant drafted in to troubleshoot the market process. The consultant “suddenly springs to life after this rather desultory conversation with the lawyer,” recalls Weston. “She said, ‘Well, the thing is that Billingsgate has a cooking school, and we were wondering if you'd like to be involved in some way’. [...] I thought, number one, she's not read our website properly because she doesn't understand that’s not actually what we do, and number two, this sounds remarkably like she's trying to buy me off.” Both a colleague of Weston’s and her lawyer confirmed to The Londoner that she had told them about the comments on the day of the call.

The Londoner put this claim to the City of London Corporation and the consultant directly. Responding on behalf of both, a Corporation spokesperson said the consultant “refutes in the strongest possible terms any indication of impropriety”. He described the meeting as being part of the City’s “commitment to listening to all viewpoints as part of the Parliamentary process” and said it was “wholly inaccurate and misleading to represent this conversation as being anything other than informing the campaigner about the food school activities at Billingsgate market given the campaigner’s own background”.

“Any other interpretation is potentially defamatory, and serious consideration is now being given to pursuing legal avenues,” he said. The City of London could not provide contemporary notes of the meeting, while Weston’s are spare. Her note simply reads: “fish school?!!”

Whatever was said in that meeting, it was enough to piss Weston off. She assembled an informal legal team — a retired patent attorney who lived next door and a legal student she happened to meet in a pub — and rang up the parliamentary clerk to tell him: “I’m fighting every step of the way and I don’t care if I lose.” Just weeks later, she was summoned to parliament to make her case before the Court of Referees.

The missing opposition

When I began looking into the markets bill, I hadn’t been expecting opposition to come from middle class philanthropists. I had expected some kind of grassroots pushback from within the big markets themselves. But there was nothing. The traders, when they were heard from at all, seemed to speak only through the indirect medium of City of London press releases.

Confused about this apparent quiescence, I head down to the two markets on a midsummer dawn to find some answers. But at Billingsgate, there are few to be found. Everyone has the same line: “Head office says we’re not allowed to make any comments”; “you’ll have to go through our upstairs”; “you’ll have to ask my boss”. The few bosses around all give a similarly guarded “no comment”. If not for the bacon and scallop bap at Billingsgate Cafe, it would have been a wasted trip, capped off by minor humiliation: leaving the market hall, I lose my footing on something slippery, flailing to avoid falling. “No dancing!” shouts a trader, deadpan.

Mercifully, Smithfield’s flocks of white-coated, blood-Pollock’d salesmen are chattier. Many are disgruntled, feeling left in the dark. John, who has been selling lamb at the market for 16 years, says there was “no job security”, but seems resigned to the situation, saying: “What do we do, go on strike? Be realistic”. When the City claims market tenants back their plans, they mean the Smithfield Markets Tenants’ Association (SMTA) and the London Fish Merchants Association, which represent the markets’ business owners. The staff here don’t have a say in these organisations, don’t appear to be told much by it, and don’t have a union to represent their own interests.

“I’ll be honest with you, the governors had a payout,” John says. The compensation package for the two markets is understood to total £317m (£167m for Smithfield and £150m for Billingsgate) and is divided between around 90 businesses. The City refused to confirm the figures, saying they were “commercially confidential”. Far from the underdog, one person I spoke to saw the traders as having the upper hand in negotiations with a local authority trapped between a legal requirement to provide the markets and a strong desire to leave the game.

Sorry to interrupt. We just wanted to take you behind the scenes. Reporting like this is old-fashioned, boots on the ground stuff. We send our journalists out into the city, away from their laptops, to be in the rooms where the events they're covering are actually happening. Our reporters spend their days away from their desks, talking to real people, and digging through council documents.

This sort of in-depth journalism doesn't come cheap. This is why it's getting rarer. A lot of media companies have given up on it, instead churning out clickbait articles that have little connection to local areas. But we believe people are still willing to pay for deep dive, properly reported work.

Already, over 700 of you have signed up as paying members to prove us right. But now we have a big target: 1,000 members. We've made it easy too: with our summer discount, a Londoner membership is just £1.25 a week. That's less than a daily coffee.

We don't rely on billionaire oligarchs, or huge companies to fund us. We just need the people of London and beyond. If you like what we're doing, please consider supporting us.

At Smithfield, John advises me to speak to one of the bosses, “if you can catch one of them. [...] But then again, they’ll keep as schtum as possible”. I do manage to catch a boss — and a big one too. When I ask for Greg Lawrence at one of his several businesses, the man behind the counter responds: “I, II or III?”. The man I’m seeking, Greg Lawrence I, has been followed into the meat business by two generations of Greg Lawrences since arriving at the market aged 16 in 1966. Today, he’s the chair of the SMTA and an elected City councillor. Stocky and bald but for a pair of imperious eyebrows, Lawrence has the aspect of a man in command. Talking to me in front of one of his shops, he says he will be “emotional” to leave the old market behind, but insists it’s “time to go”, as businesses need space to grow.

He’s as emphatic as he is vague about replacing the market. “New sites will be identified, tenants will go to a new site, and that’s as good as I’ll give you on that,” he tells me, rubbishing suggestions of job losses. Lawrence is genial throughout our chat, and generous with styrofoam cups of tea.

But when I mention the petitioners, he turns severe, calling it “nonsense” and “a wind up”, even suggesting the fishmongers were exaggerating their use of Billingsgate. On compensation, he points out that the markets are home to “serious businesses” with huge turnovers that will need to fit out any new premises, but turns vague again when asked how the figures were reached. “The formula was the formula,” he says, “it was agreed by the City and that suited everyone in the end”.

Some fear the payout may be too modest. “It’s all very well getting the compensation to move, but that’s not enough to go away and build a new site, is it,” a meat salesman called Simon tells me. One owner, who refuses to be quoted, admits an outside investor could be required.

Several butchers I speak to repeat talking points from both sides of the argument between the City and the petitioners, complaining about the markets limited trading hours, inefficient logistics capability and outdated infrastructure, while emphasising the important service to their customer base, which is increasingly dominated by minority communities — Turkish and South American butchers in Smithfield's case, South Asian and Afro-Caribbean in Billingsgate’s.

A stay of execution

In the stuffy wood-panelled Commons committee room, with eight relatively unknown parliamentarians arrayed in a horseshoe formation ahead of her, Weston steeled herself for an abrupt dismissal. “I was told there was a really high chance they would just shut me up,” she recalls, though she needn’t have worried. Jonathan Davies MP thanked her for invoking her democratic right to convene the court, noting that it was only the third time this century it had met. Chair Nusrat Ghani MP gave her plenty of latitude to explain the impact the potential loss of the markets would have on the capital’s small, diverse butchers to MPs — this being all she could rely on, having been told by her lawyer that she didn’t really have any legal arguments.

By contrast, the City’s parliamentary representative, known as the Remembrancer, gave a dry delineation of points of law, citing Erskine May and the joint committee on private bill procedure. The decision, ultimately, was a compromise. Weston was denied standing, but the court also found that the fishmongers’ “right to be heard should not be limited”. In other words, they had the right to give evidence to MPs as the legislation passed through parliament.

The bill is now in limbo, rated “red” on the City’s risk matrix. No date has been set for committee, with the City stuck between a potentially messy opposed bill committee or trying to strike a deal. But the fishmongers aren’t budging until they have a replacement. “We need a guarantee, handwritten, on paper,” Aras Swara, co-owner of the Mediterranean fish shop on Ridley Road, tells me. “They talk in a good way, but I don’t trust them”.

While myriad possible locations are bandied around by market salesmen — Nine Elms, Barking, Walthamstow, Rainham, Whitechapel — none have been identified as a new site, and the City says it’s “for traders to decide”. It claims 70% of Smithfield traders want to move to a “New Smithfield”, with the remaining 30% transferring their businesses to others. At Billingsgate, the City press release says, 90% will relocate to a single site, with the rest considering their options.

The longer finding a site takes, the longer the bill will take. Parliament ultimately determines its scheduling, but the City acknowledges “it is an expectation of Parliament and therefore incumbent of promoters of bills to try to resolve any issues” that might take up undue time. Robbie Owen, a parliamentary agent at Pinsent Masons, has speculated the process could “easily be up to two years, or even longer”.

Nonetheless, the City is preparing for life without the markets. The timing of outsourcing Billingsgate’s cleaning staff in February was “no coincidence”, according to GMB union organiser Anna Lee. In June, the Markets Site Regeneration Programme (MSRP) was launched to lead regeneration plans. Billingsgate, which is leased from Tower Hamlets in return for “the gift of one fish”, is expected to deliver up to 4,000 homes and a new bridge between Poplar and Canary Wharf. Grade II* listed Smithfield, meanwhile, will follow the path of its poultry market building, which shut in 2023 to be turned into a new home for the Museum of London. The remaining market buildings will be refurbished as an “international cultural and commercial destination”, while the MSRP’s task of developing a strategic masterplan for the wider Smithfield/Barbican hints at one potential occupant: City minutes discussing renewal of the Barbican Centre confirmed the cultural centre was looking at “linking up with other locations e.g., Smithfield”.

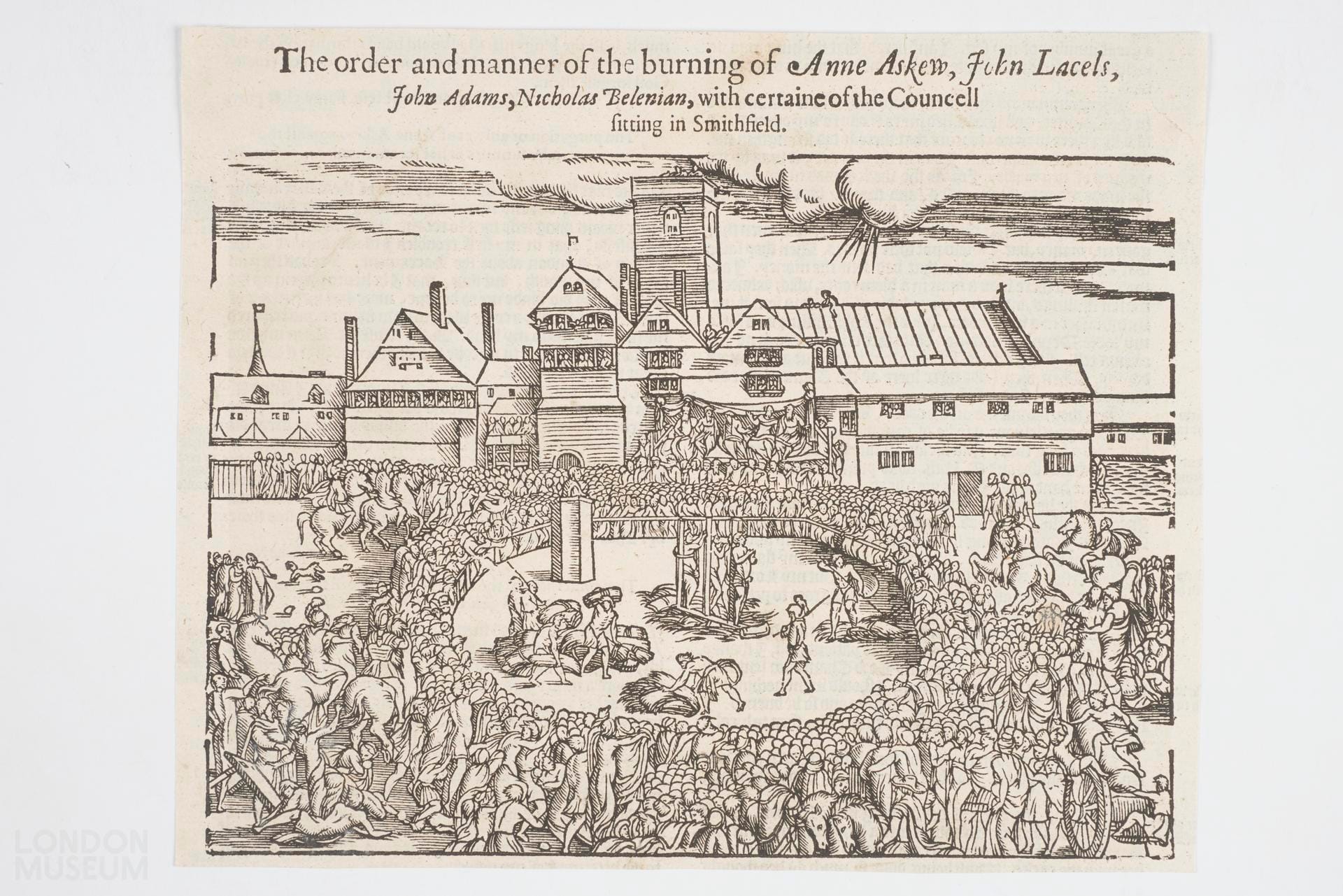

However successful these transformations — and whatever the outcome of the fishmongers’ intervention — the end of the markets in their current form will be a milestone in the exile of tangible industry from the centre of the city. Billingsgate is already a half-lost cause in this sense, pushed out to Poplar in 1982. But Smithfield, the location of Wat Tyler’s murder and William Wallace’s hanging, drawing and quartering as well as centuries of trade, is the inheritor of a long, unbroken history of sweat and entrails. It's remarkable that nobody, not even Weston and the fishmongers, opposed the curtailing of this dynasty on its own terms. With its siblings at Spitalfields and Covent Garden long ago chased out to the peripheries by ceaseless tide of urban development, the meat market has been on borrowed time for decades. A London institution beloved but not wanted, Smithfield is the last man standing in a battle long since lost.

Editor’s note: this story was corrected on 23 August to reflect that the commitment to help traders find a new market within the M25 was made simultaneously to the announcement of Smithfield and Billingsgate’s closure.

If you enjoyed Daniel's story and want to get sent similar investigations on the city's future, why not sign up to the Londoner newsletter today? This means you'll get weekend longreads like our piece on the strange death of east London's radical bookshop and Monday briefings like our comprehensive analysis of the wet-wipe island in the Thames delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.