Our Saturday stories are free for all to read — but we can only produce this kind of work with your help. If you're a fan of today's piece, please do consider becoming a paying member.

In the labyrinthine basements that spread like roots below the London County Hall building, there’s a windowless room. In it 15 residents stand, with only a shallow pool and some painted murals of the world outside their four walls for company. One just celebrated their 30th year birthday. Many have never seen natural light or breathed outside air in their whole lives. There they sit, permanently on display to those who have paid a few pounds for entry. The prison in question is in the London Aquarium, and its prisoners are 15 Gentoo penguins.

But over the last year a growing viral campaign has emerged to free the “Gentoo 15”. It’s brought together celebrities like Chris Packham and MPs, animal rights charities and thousands of members of the public. This is the inside story of how 15 penguins got trapped deep under the capital and the unlikely trio whose campaign to save them became a national phenomenon.

“Penguins have been born in there and may die in there, having never had fresh air, never seen daylight,” Isobel McNally, the campaigns officer for animal rights charity Freedom for Animals, tells me when we speak on the phone. Having spent the last two years spearheading the campaign to free the birds, her knowledge of their situation is second to none.

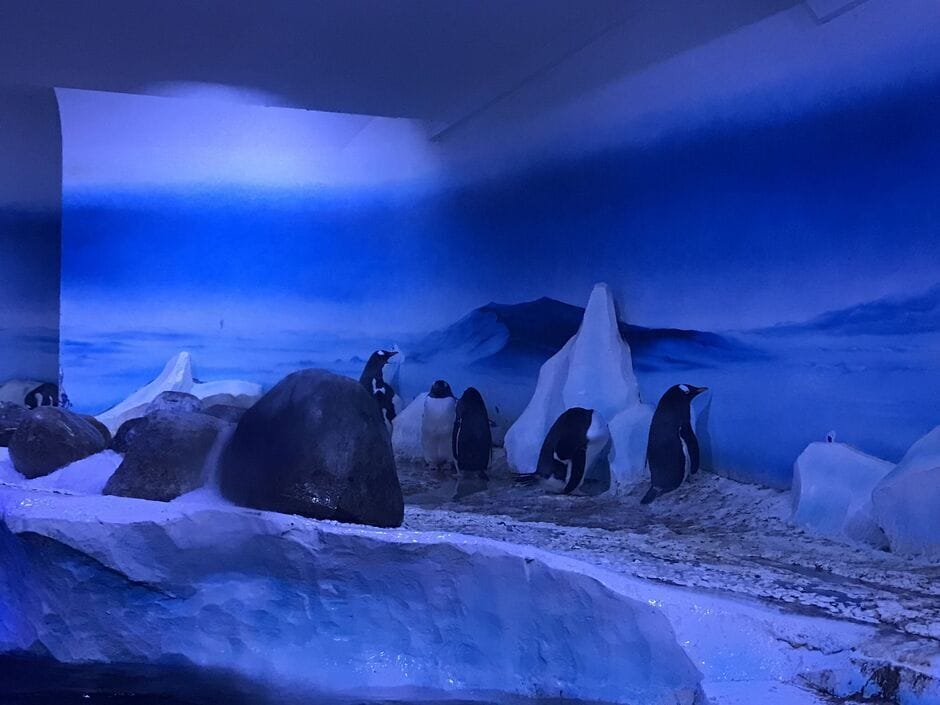

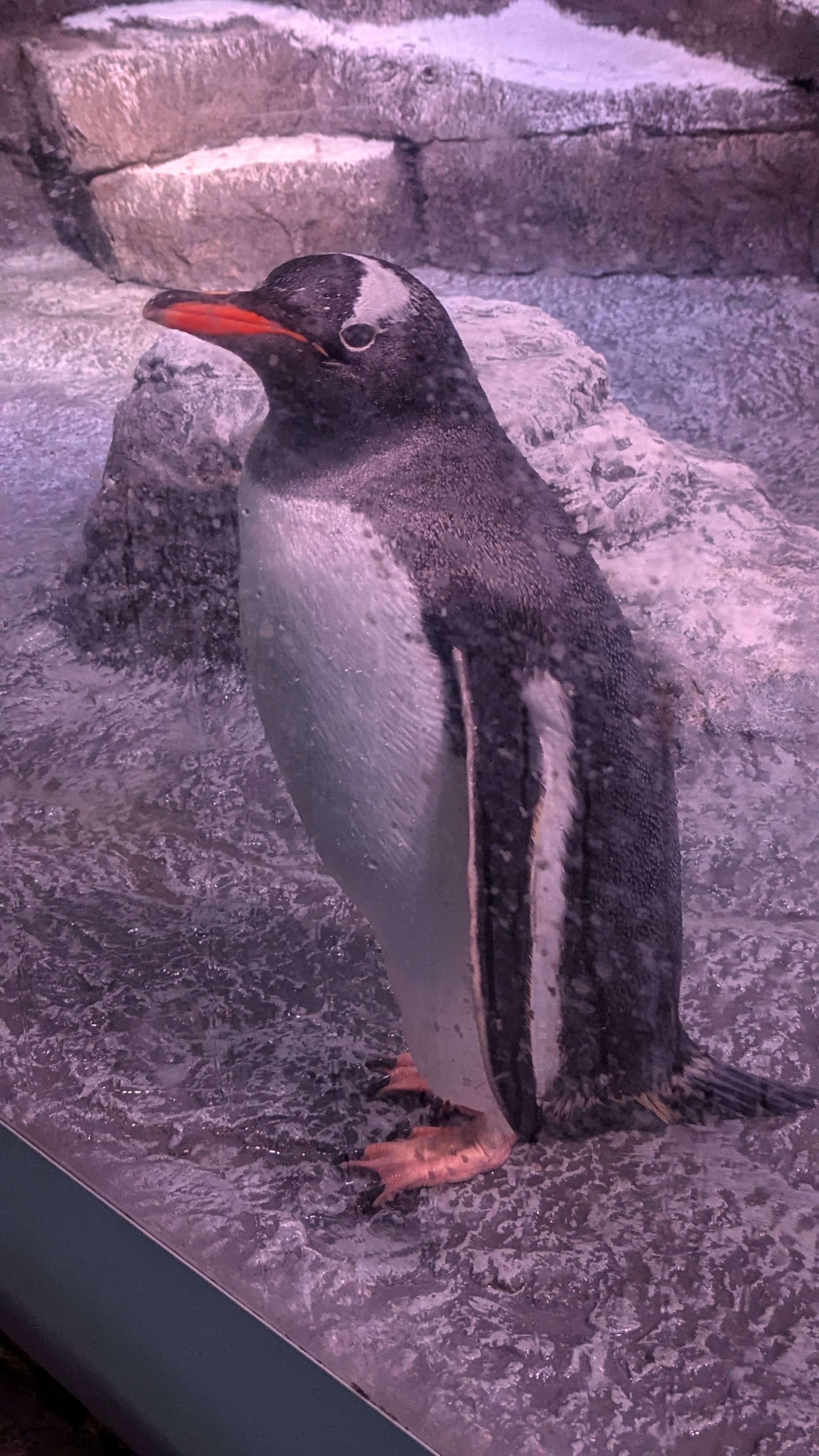

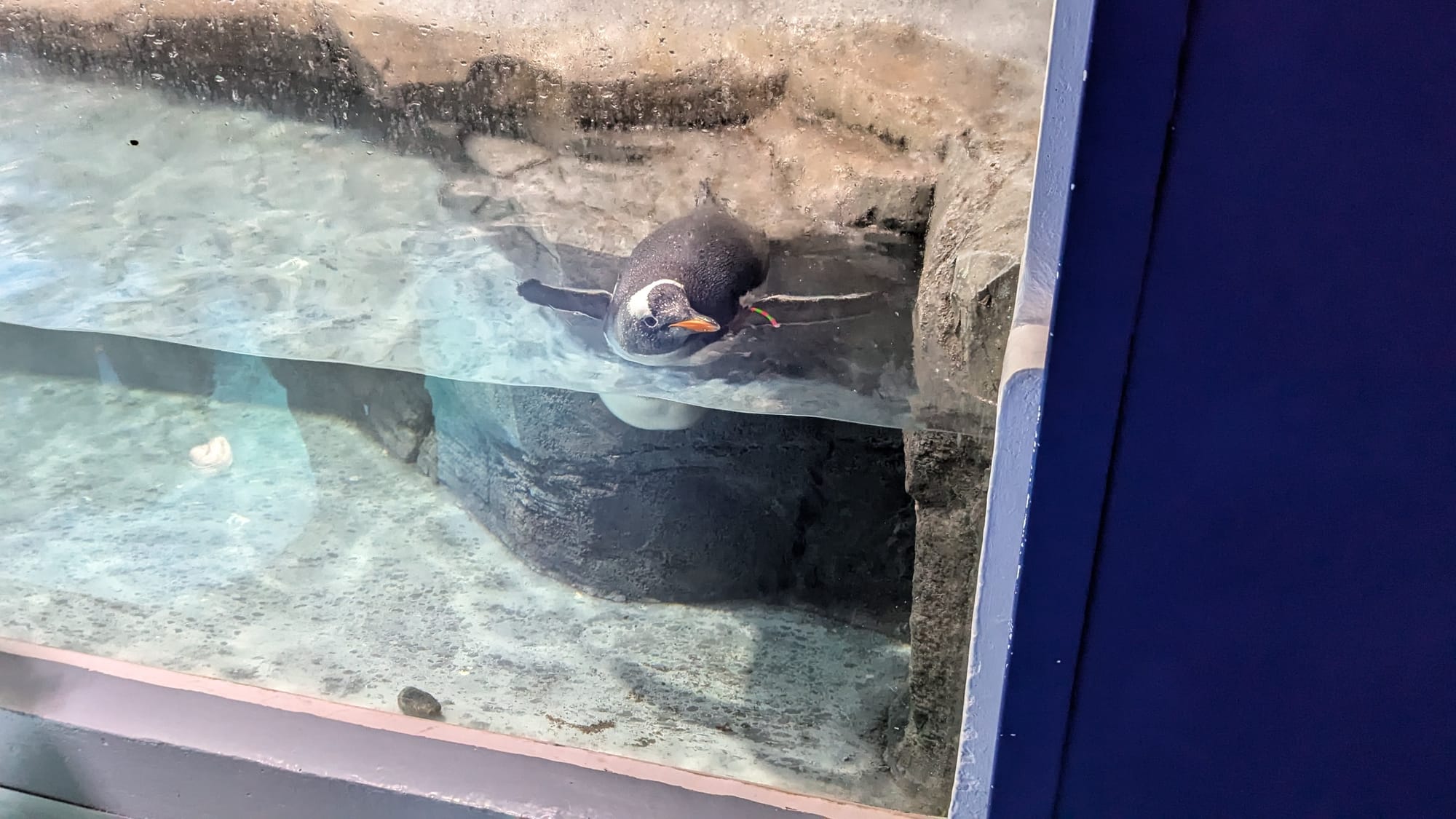

The enclosure in which the Gentoo 15 live is definitely unnatural, buried deep underground deprived of fresh air and natural light. It’s also small, though it’s impossible to say its exact size — when asked, Sea Life wouldn’t disclose this information, other than to say it meets minimum legal standards. Set behind a panoramic perspex window, its walls are painted with a mural depicting the Antarctic mountains expanding onto the horizon, like the false sky in The Truman Show. Gentoo penguins are the strongest swimmers and deepest divers of all penguins — able to swim at speeds of 22mph and to depths of some 600ft. By comparison, there’s just 7ft before you hit the white plastic bottom of the small pool in their London Aquarium cell.

Unlike their cousins at the open-air enclosure at London Zoo, the penguins in the basement of the Sea Life London Aquarium are a relatively new phenomenon. The London Aquarium only opened in 1997, with a modest collection of marine life. But everything changed in 2008, when the site was bought by entertainment behemoth Merlin, the parent company that runs the Legoland parks, Alton Towers, Chessington World of Adventures, the London Dungeon — basically every major UK theme park and tourist attraction. They also run the country’s Sea Life centres, and to turn the site into its latest Sea Life attraction involved a £5m refurbishment; enough to bring the kind of headline attractions that can entice the big crowds.

But the London Aquarium is unlike most of Sea Life’s other sites. One of the growing list of tourist attractions squatting inside the former London County Council building, it’s as far from custom-built for wildlife as you can get. An initial cohort of 10 feathery Antarctic residents arrived in 2011, a purchase from Edinburgh Zoo. In 2015, they were evicted and moved to a room in a different part of the building after their old spot was taken over by the newly opened Shrek’s Adventure attraction.

The aquarium has partly defended its choice to keep the Gentoos in captivity with the fact they host a breeding programme. But McNally stresses that the species aren’t even endangered in the wild. And often, she tells me, those newly bred penguins from the enclosure will be sent away from their parents to entertain crowds at other Merlin attractions, like Legoland.

McNally has spent much of her adult life as an animal rights campaigner, aiming to make people see animals as “individuals”, not objects. It started when she was a student at the University of Manchester and stumbled across a protest against the university’s use of animal testing. When she joined Freedom for Animals in 2021 it was initially to lead the group’s campaign to stop the use of live reindeer at Christmas events. But by 2023, a growing flood of complaints from its web of dedicated volunteers and sources put the Gentoo colony at the London Aquarium on the charity’s radar.

Whenever a new campaign is in the works at Freedom for Animals, the first step is usually to call the investigators. Teams of anonymous volunteers, those investigators will go undercover, feigning to be a visitor, a volunteer or a staff member, and document the real life conditions of the captive animals in question. McNally is very guarded when I try to find out more about the process — central as it is to the charity’s work — but admits that, even for experienced investigators tasked with infiltrating slaughterhouses or dodgy wildlife parks, the visit to the London Aquarium in 2023 was “considerably worse than what they’re normally seeing”.

“Of the nine penguins I could see, at least four sat facing the wall,” the investigator later wrote. “One of them didn’t move the entire time I was there. He just stood, facing the wall, lifeless, staring at the painted wall that was mimicking his real home.”

Working out whether the conditions in captivity are causing a problem for animals can often be quite hard. When the Financial Times tried to find out if there was a disproportionate number of animal deaths at the London Aquarium, their Freedom of Information request to the local council came back empty handed. After a 2018 BBC exposé found that a third of the animals at a Sea Life centre in Great Yarmouth died in the space of one year, the company has only allowed council inspectors to view an online portal displaying their annual stock take of animals, rather than giving inspectors access to copies, which could then be publicly accessible under a Freedom of Information request. (Sea Life insists this still adheres to all the legal requirements and that the BBC story misinterpreted the data).

While there are some species, like parrots, that will self-harm, tearing and ripping away at their own feathers, if enclosed in a tiny space. For other species, the observable behaviours can be less blatant. But experts say they’re still there if you know what to look for. “They have elaborate mating displays and complex social behaviours. But visitors to the Sea Life London Aquarium, or any other captive environment, will never see these,” wrote Professor Helen Lynch, an expert in Gentoo penguins from Brook University in New York. “Gentoos in captivity swim in desperate circles, vocalise only rarely and display few of the complex interactions. Most cruelly, they show the biomarkers of illness and old age, even as their protected environment keeps them alive in solitude and suffering for decades.”

After weeks of consulting with investigators and experts, Freedom for Animals wrote to Merlin in 2023 with a demand: free the penguins from the basement. But they received no response. Their only option was to go public. In the days before the official launch of the campaign, McNally decided to visit the enclosure in person for the first time, to stand face-to-face with the captive penguins she was about to embark on the “Sisyphean task” of trying to free. The reality of it; dimly lit, smelling of guano and flooded with gawking visitors was deflating. “The people around were still behaving like this is just tourism,” she says. “This isn’t tourism, this is a prison.” Ruminating in the pub afterwards, she recalls, the experience made her all the more resolute. But to get the campaign off the ground, they would need help from an unlikely source.

For Steph Spyro, deputy politics editor (and occasional environment correspondent) at the Daily Express, it was a typical day at work when Freedom for Animals announced its campaign to free the aquarium Gentoos. She published a quick story based on the charity’s press release — only to find, a day later, that she had received a legal threat from Merlin Entertainments. If she didn’t remove the word “captive” from her story about the penguins, they said, the company would “be forced to take legal action”. She was dumbfounded, she recalls, “because the penguins were captive in every sense of the word”.

She wrote a piece about the threat. Readers responded, outraged on the paper’s — and the penguins’ — behalf, and it snowballed into a campaign, with dozens of articles from expert penguinologists penning articles condemning the conditions. This fed into the flurry of campaigning by McNally and Freedom for Animals, which included putting together an open letter signed by celebrities like Chris Packham and eco-industrialist Dale Vince, as well as media appearances, nationwide protests and a petition. At one they held last year outside the London Aquarium, a 30-something man queuing to enter instead decided to pick up a placard and join the protestors.

“Every conversation I have, whether it's with MPs or with friends, I tell everyone about the plight of the penguins,” Spyro says. “If that legal threat hadn’t happened, I don't think I would have become the penguin campaigner that I have.” It was one of her articles that also put the penguin’s plight in front of parliament.

“There's only two vets in parliament, so there's not many people there with expertise in animal welfare,” says Dr Danny Chambers, the Liberal Democrat MP for Winchester and former veterinarian. As a result, whenever stories about animal welfare bleed into Westminster, he is often one of the first politicians to get the call. It was one such call from Spyro that pulled him into the London Aquarium campaign. He doesn’t share the more militantly anti-zoo beliefs of Freedom for Animals, but something about the specific plight of the Gentoo 15, denied access to natural light and fresh air, struck a chord. “You're working in parliament a couple hundred feet away from where they are actually living and I thought it seemed just so clearly wrong,” he explains. “I said: ‘If I could do something to help, then I will’.”

He ended up filing an Early Day Motion — a formal call for a parliamentary debate that can garner support from across the political spectrum — at the end of last year. The majority only ever tend to get one or two signatures. But his EDM now has some 24 signatories, its backers ranging from the left-wing Green Party to the ultra-conservative DUP, though it is yet to be offered a slot for a Commons debate.

For Chambers, the campaign is about a lot more than one enclosure; it’s about national pride. “It's at the heart of London, next to parliament and the London Eye. It must be one of the most visited aquariums in the country; tourists from all over the world go there,” he explains. “If we're saying that that is an acceptable way to treat animals, I think it reflects badly on us as a country.”

Now, Chambers tells me he’s speaking to his local wildlife park — an 140-acre open air zoo already home to some penguins — to see if they might be open to taking on 15 more penguins; a potential retirement home for London’s Gentoos far away from the manic crowds of the capital.

We tried to speak to Sea Life for this article but, almost a week after first making the request to the communications agency that acts for Merlin, we were told no-one would be made available. Instead we were sent a pre-written statement that denied the conditions were inhumane and stressed that they were “committed to delivering the highest levels of care through our team of dedicated welfare experts” and met the “high standards” outlined in government zoo practice guidelines. The enclosure provided “an excellent balance of water and land for the penguins”, they said, as well as “space for them to ensure they have sufficient privacy”. The penguins have regular checks from internal and external vets and recently the aquarium had its zoo licence renewed by Lambeth Council following a full inspection.

I decide to visit the penguins myself on a sunny afternoon in early May. Dragging myself through the Southbank crowds, I descend into the aquarium’s murky depths, past the screaming children, the buckets collecting leaking water, the cracking paint murals, the bubble tea stands. The star exhibit, the penguins are kept from visitors until the last moment of their visit.

You can hear the speakers mimicking the natural calls of the penguins long before you see any of them. Initially, the crowds block any view through the windows. Only when it thins slightly do I get a sense of daily life for the Gentoo 15. Most of the colony are gathered in the far end of the enclosure as far from the prying eyes of the crowds as possible. But there’s little privacy to be had in such a wide open space. It’s breeding season, so a handful of the penguins are sitting on nests. The rest are mostly standing, unmoving, looking at the faux rocky edifice and painted antarctic murals that line their enclosure. I lock eyes for a fleeting few seconds with one of the few Gentoos not exiling itself to the far corner; he starts pecking frantically in the direction of a toddler that’s repeatedly tapping on the glass.

I look at the “who’s who” board that lists the names of the 15 penguins, each identified by a coloured armband. I spy Riply and Ziggy standing in the far end of the enclosure facing the wall. The shallow pool is empty almost the entire time I’m there, except for Gilbert who’s swimming from end to end in split seconds, before giving up, and staring aimlessly at the crowd of faces massing around her on the other side of the glass. Eventually, she dives out of the water to the rapturous squeals of the onlookers, and heads to the other side of the enclosure, away from the crowds, followed by Honey. And immediately most of the massed sightseers split off, following them to the other side. Slowly, they engage in this almost hypnotic back and forth, as the duo waddle away from the crowd only to be mercilessly tracked everywhere they go. The longer I watch it, the more I start to have visions of increasingly crazed rescue plans.

I desperately, hopelessly, wait for the crowds around the enclosure to disperse, but the waves of new onlookers are relentless, almost mechanical in their timing. I look back at the sign listing the names of the penguins. Eventually, I notice that below each name, and their colour-coded armband, there is a date of birth. The week before my visit, the colony’s matriarch Polly celebrated her 30th birthday. She had spent every year of that life in captivity.

I have to pull myself away. I walk past the Conservation Cove cafe, the VR videos of sad polar bears, the penguin mugs in the gift shop, the slushy machines and the ads for Shrek's Adventure, across the wooden floors of the County Hall and out of the double doors. When I emerge back out into the outside world, the sky has clouded over, the sun faded and barely visible. But it’s a sky and sun that Honey, Gilbert, Polly, Ziggy and Ripley — that all of the Gentoo 15 — may never see for the rest of their lives.

Do you want to see the Gentoo 15 freed? Or are you an avid London Aquarium fan? Sound off in the comments below.

Comments

How to comment:

If you are already a member,

click here to sign in

and leave a comment.

If you aren't a member,

sign up here

to be able to leave a comment.

To add your photo, click here to create a profile on Gravatar.