Welcome to The Londoner, a brand-new magazine all about the capital. Sign up to our mailing list to get two completely free editions of The Londoner every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

It’s a grey day in October 2016, and Zack Polanski is sitting in a drab Costa Coffee opposite Koko nightclub in Camden, talking about his latest political setback: failing to get selected as an MP candidate for an upcoming by-election. The future Green Party leader is being consoled by a somewhat unlikely companion: Mark Shooter, then a long-serving Conservative member of Barnet Council, who in 2024 became Reform’s first councillor in London.

But the politics was just small talk. More than anything, Polanski, who last week was resoundingly elected leader of the Greens, was trying to avoid eviction. Shooter was Polanski’s landlord and under investigation by Camden Council for illegally renting out a bedsit to 14 people, who had to share a single kitchen and, at times, a single working shower. The council was looking for tenants like Polanski to support their prosecution.

Outside the coffee shop, it was dreary and overcast; one of those humid autumn days where the threat of a downpour is always on the horizon. But Shooter was offering Polanski and another tenant, Yaniv Garber, a ray of sunshine: the chance to avoid eviction and stay in their flats, working as “wardens” for a new hostel Shooter planned for the site. “In terms of legal stuff with Camden, I can’t have anything to do with it, I’m not meddling at all with that. You have to do what you think is right,” Shooter told the duo. Later in the conversation, after Polanski mentioned consulting a solicitor friend, Shooter said: “Please don't mention about me wanting to help you guys out, and you helping me out.”

Recounted to us by Garber, this somewhat surreal scene, emerged as part of The Londoner’s investigation into Shooter, who last year defected from the Tories and became the first Reform Party councillor in the capital. When we started that investigation into Shooter, we had no way to know it would end with revelations that would encompass the leader of Reform’s eco-populist rival.

In time, we learned how Shooter has run two properties filled with crammed bedsits in Camden, one of which is a segmented building on the site of a former four bedroom house that is now designed to be rented to up to 33 people. Tenants of his have been made to pay rent in cash in order to, as the head of a judicial property tribunal put it, “obscure any audit trail”. Responding to our investigation, a leading housing campaign has now called for Shooter’s resignation.

London's first Reform councillor

For most of his 15 years in public office, Mark Shooter was a largely unnoticed backbench Tory councillor in Barnet, splitting his time between political duties like chairing an internal council pension fund committee and his day job working in property development.

That is, until November 2024. A few months after a failed bid to become the leader of the Tory opposition on Barnet Council, Shooter defected to the insurgent right-wing political party led by Nigel Farage. At the time, Reform didn’t have a single councillor in the capital (though the number has grown to six after more defections).

In recent weeks, Reform councillors across the country have been suspended or have had to step down amid various scandals, so we decided to take a closer look into their representatives in the capital. While doing so, we noticed that Shooter was the co-owner and director of a company called Kingscroft Estates. In December 2016, Kingscroft was dragged to the Highbury Corner Magistrates’ Court by Camden Council and accused of running an illegal bedsit. A townhouse on Hurdwick Place, next door to Mornington Crescent station, the building had been subdivided into 14 bedrooms, which shared one kitchen, one bathroom and two showers, despite never having been granted a HMO license, something a landlord who wants to rent to multiple households must have. The property brought in £84,000 a year in rent for Kingscroft and Shooter, one of its two named directors.

Know of any other stories similar to this? Let us know using the anonymous form below or email our editor.

The judge found Kingscroft guilty and fined them £4,000 and an additional £4,340 in council legal fees. Shooter told a reporter from the Camden New Journal in attendance at the court that he had “nothing to do with it”, despite being the co-owner of Kingscroft Estates and the director who signed off on its accounts each year.

After the enforcement action, in early 2017 four tenants decided to take Kingscroft to a residential property tribunal, a specialised legal body that settles disputes between landlords and tenants. These tribunals can require landlords to repay rent to tenants if they had been renting to them illegally, known as a rent repayment order.

The case revealed that Kingscroft had served its tenants with Section 21 “no fault” eviction notices — a procedure that was legal then but is now set to be outlawed. Tenants claimed the property was frequently in a bad state, with rat infestations, broken sinks and a shower in the basement that had broken and been left unfixed for months, leaving the 14 tenants sharing one working shower.

One of the details that stood out was the fact that every tenant in the property was required to pay their rent in cash every month. Often, the cash would be placed in envelopes and left in the bedrooms or slid under their bedroom doors when they left for work, to be collected by the landlord’s agent — a man called Danish Zafar. In his judgement, Neil Martindale, the head of the tribunal, explained how even though the tenants “provided evidence of functioning bank accounts” and Kingscroft used bank transfers to pay contractors, “for reasons that were not clear to the tribunal” the landlord “had chosen” to have cash rental payments. “There was no evidence of widespread payment arrears or history of bad debts involving these four tenants that might have made such arrangement necessary for the landlord,” they went on, “and instead it served simply to obscure any income audit trail.”

The tribunal also found against Kingscroft, which was ordered to pay £6,363 in back rent to the four tenants. It was after reading this judgement, which has not been previously reported on, that I was able to track down and interview Yaniv Garber.

Enjoying this edition? You can get two totally free editions of The Londoner every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

A meeting in Costa Coffee

Thirty-nine years old, slight with bright blonde hair, Garber is an animator in the film industry and had moved into the house in September 2015 after being secured a room by a friend. The rent was affordable, but the problems in the property led to concerns about their councillor landlord. “I think they’re the definition of a slum landlord,” Garber tells me, based on his experience as a tenant. “We moved in and paid rent literally under the door, doing it in cash envelopes.” As we chat, he shares with me a dossier of evidence he compiled for their tribunal case in 2017, including texts about rent payments and eviction notices, and photos of disrepair.

He also shared evidence of that meeting in Costa Coffee, where Shooter offered the chance to avoid being evicted. It was then that he mentioned that one of his flatmates, who also attended that meeting and who recommended he move to the property in the first place, was none other than Zack Polanski, the newly elected Green Party leader. I hadn’t noticed the link before — Polanski used his birth name of David Paulden in the legal documents (he changed his name when he turned 18 to his grandfather's surname and to differentiate himself from his stepfather, also called David).

At the time, Polanski was still a member of the Liberal Democrats, but soon would defect to the Green Party. “He was a rogue landlord who was essentially trying to buy us off,” Polanski told The Londoner when we caught up with him this week. “I took a picture of the shower once, of what state it was in. A magazine… was doing a top 10 worst conditions that people are living in London and used my photo.”

Ever since the end of the court case with Polanski and Shooter, the Hurdwick Place property has been operating as a hotel called the Hurdwick. The complaints about the conditions in the property, which is still owned by Kingscroft, haven’t stopped. When The Londoner took a look at its reviews on TripAdvisor and Google, there were pictures of rusted, broken shower heads and holes in the ceiling.

The 33-person HMO

The Hurdwick Place house isn’t the only property run by Kingscroft. When going through the company's corporate filings, we found references related to 34 Shoot-Up Hill in Kilburn. Both the house in question, and the bizarrely-named road it sits on, were well known to me. Devoted Londoner readers may recall that I have been a Kilburn resident for the last half a decade, even writing about the area’s forgotten Irish roots. I live around the corner from Shoot-up Hill, which is a street lined with detached houses and a spattering of low-rise apartment blocks.

According to planning documents on the Camden Council website, it was once a four-bedroom detached family home. But at some point it was redeveloped into a new building that was split into four separate properties (34A, B, C and D), so it could be used as a HMO. It was bought at auction in 2010 by Kingscroft Estates, and is now licensed by Camden Council to house a maximum of 33 people across its 24 bedrooms.

Sorry to interrupt. We just wanted to take you behind the scenes. Journalism like this is old-fashioned, boots on the ground stuff. We send our writers out into the city, away from their laptops, to be where the events they're covering are actually happening.

This sort of in-depth journalism doesn't come cheap. This is why it's getting rarer. A lot of media companies have given up on it, instead churning out clickbait articles that have little connection to local areas. But we believe people are still willing to pay for deep dive, properly reported work.

Already, well over 800 of you have signed up as paying members to prove us right. But now we have a big target: 1,000 members. We've made it easy too: with our summer discount, a Londoner membership is just £1.25 a week. That's less than a daily coffee.

We don't rely on billionaire oligarchs, or huge companies to fund us. We just need the people of London and beyond. If you like what we're doing, please consider supporting us.

Shooter’s record as a landlord raises some awkward questions for the party he now belongs to. Shooter is one of Reform’s main politicians in London, a city that Farage has told officials will be a “priority” to win seats in. Alex Wilson — Reform’s solitary member on the 25-person London Assembly — has been vociferously critical of Labour MP Rushanara Ali, who stepped down as homelessness minister after she evicted her own tenants before subsequently hiking up the rent. Wilson called these actions “sheer hypocrisy” that showed Labour “weren’t interested in representing the people.”

This is a government of champagne socialists.

— Alex Wilson AM 🏴 🇬🇧 (@AlexWilsonAM) August 8, 2025

Champagne for them, socialism for everyone else! pic.twitter.com/Hi23RfwTN1

Will the same standards be held for their own politicians? A spokesperson for Reform claimed the “resurfacing of these decade-old accusations is clearly politically driven” and that all “matters concerning the properties owned by the company, in which Cllr Shooter held a minority stake, were fully resolved and in strict compliance with the law.” (According to Companies House, Mark Shooter owns between 25–50%, alongside a business partner who also owns between 25–50%). The Reform spokesperson said the maximum number of 33 people licensed to live in the 24 bedrooms at 34 Shoot-Up Hill had never been reached.

But others are less ambivalent about the situation. “Mark Shooter must resign. It is telling that a politician from a party claiming to stand against the establishment is in fact a rich landlord, profiting from some of the most exploitative housing conditions in our city,” Elyem Chej, a spokesperson for the London Renters Union, one of the capital’s biggest renter’s rights groups, told The Londoner. “Members of Shooter’s party feign outrage over the actions of Rushanara Ali while harbouring unscrupulous landlords in their own ranks.”

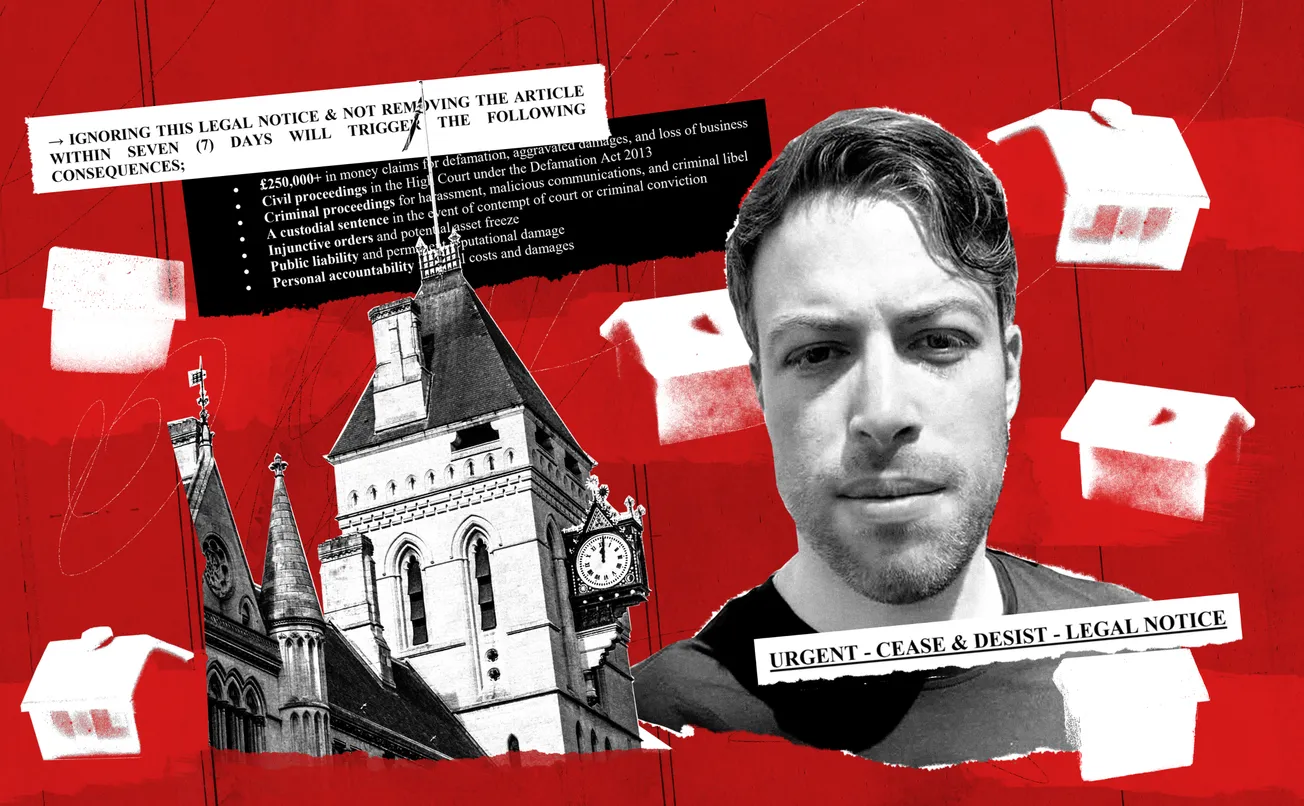

The legal letter

When we contacted Shooter for a right of reply, we received a five page letter from his lawyer, Mark Lewis. Zack Polanski was making “false and defamatory allegations” and his “motivations are both party political and part of his attack on Mr Shooter as a supporter of Israel,” the letter said. This was news to us, given we hadn’t spoken to Polanski at that point and only found out his involvement after speaking to Garber not long before we reached out to Shooter. We had made no mention of Polanski in our right of reply email to Shooter. Nor had we mentioned Israel.

Lewis insisted his client “does not accept the allegations made”, including the existence of disrepair in the Hurdwick or Shoot-Up Hill properties, and “categorically denied” he was a “slum landlord”. He added that the eviction of the tenants was "necessary" to carry out “required renovation works” and suggested that parts of The Londoner’s queries were motivated by “general envy” and an “obsessive fixation” on Shooter. Shooter’s statement to a local reporter about not being involved in the property referred to not running it day-to-day, Lewis wrote. “The idea that our client was not just dishonest, but an idiot who hoped that he could lie to a journalist about a matter in the public domain, is absurd,” he added.

Lewis volunteered that “as far as our client is aware, there is no asylum seeker” living at 34 Shoot-Up Hill and the “suggestion that there is points to the political placement of this false story”. The questions we put to Shooter made no reference to asylum seekers.

Lewis also said that the failure to get a proper HMO license at the Hurdwick Place property was because the property was “then managed by a third party company” who ignored messages from the council to get a license, and that the “former agent” was also behind the decision to collect rent in cash from the small number of tenants who “did not have bank accounts” or whose “cheques had been dishonoured” — something that’s refuted by both the tenants we spoke to and the property tribunal. The lawyer wrote that “all payments to our client’s company” from that third-party management company “were transferred electronically”.

The legal proceedings never mention a “third party company”, but point to a property manager working for Kingscroft called Danish Zafar. According to tenants, Zafar handled all rent collection and maintenance at the Hurdwick property. When The Londoner contacted him (and before he abruptly hung up) he confirmed he still works for Kingscroft.

When we put these discrepancies to Lewis, he told us he would not respond within the three working days we gave them, claiming he was on holiday and did not have access to his files. He added that we were making an “unreasonable approach” by only giving him and his client three days to respond and were “making historic allegations based upon hearsay”.

In reviewing the list of 26 businesses in which Shooter declared a role in on his Barnet Council register of interests, we noticed one that was unlike the others: a charity called the Shooter Charitable Foundation. Its Charity Commission listing says it stands for the “advancement of orthodox Jewish faith, religious education, the relief of poverty, sickness & infirmity, and the advancement of such other objects as are charitable”.

The Londoner noticed that since 2013 the charity had made several loans to Mark Shooter, worth as much as £20,000. Charity Commission guidelines advise against charity trustees receiving any potential financial benefit from the charities they run. When we contacted the Charity Commission, a spokesperson said they were formally “assessing concerns raised with us about loans made by the Shooter Charitable Foundation Limited”. They later told us that they had “issued the trustees with regulatory advice and guidance on managing conflicts of interest” that if not followed could lead to further regulatory action.

Shooter’s lawyer told us the loans were “a hypothetical breach” of Charity Commission rules “which never happened”. He did not answer follow-up enquiries we made about the regulatory advice issued by the Charity Commission.

Garber is still gobsmacked that there was such a dearth of public outcry or accountability for Shooter, beyond two fines that did little to diminish the revenue he received every year from his properties. “It enraged me, to be honest, and it still does. That's why I kept all the documents,” he tells me. “He's also someone who has a public office; it's not even someone who is hiding in the shadows, it's someone who is doing it in broad daylight.”

If you enjoyed Andrew's story and want to get sent similar investigations on the city's future, why not join up as a Londoner member today? This means you'll get weekend longreads like our piece on the strange death of east London's radical bookshop and Monday briefings like our comprehensive analysis of the beef between French curators and the British Museum delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.