This article was published by The Londoner: a new newsletter covering the capital. Join our free mailing list below to get great writing and big scoops in your inbox.

If you want to keep the heating (and lights) on at Londoner HQ, consider becoming a paying supporter of The Londoner. We're on a mission to hold the powerful to account, and for that we need our independence. As a result, we aren't backed by billionaires or private equity firms. But it's means it's only through reader subscriptions, from people exactly like you, that we can continue to do this work.

Becoming a supporter gives you access to all of the members-only content in our archive, as well as putting you at the vanguard of a media revolution. So, if you think the city deserves proper journalism, consider backing us for just £4.95 a month for the first three months.

It was 4am on the 1st of July as Jack Parker bolted upright in the basement below the Scarlett Letters bookshop. From above, Parker could hear drilling. Then a “thunderstorm” of footsteps. Startled and bleary-eyed, they hurriedly dressed, then crept up the stairs into the main bookshop. What they saw “horrified” them.

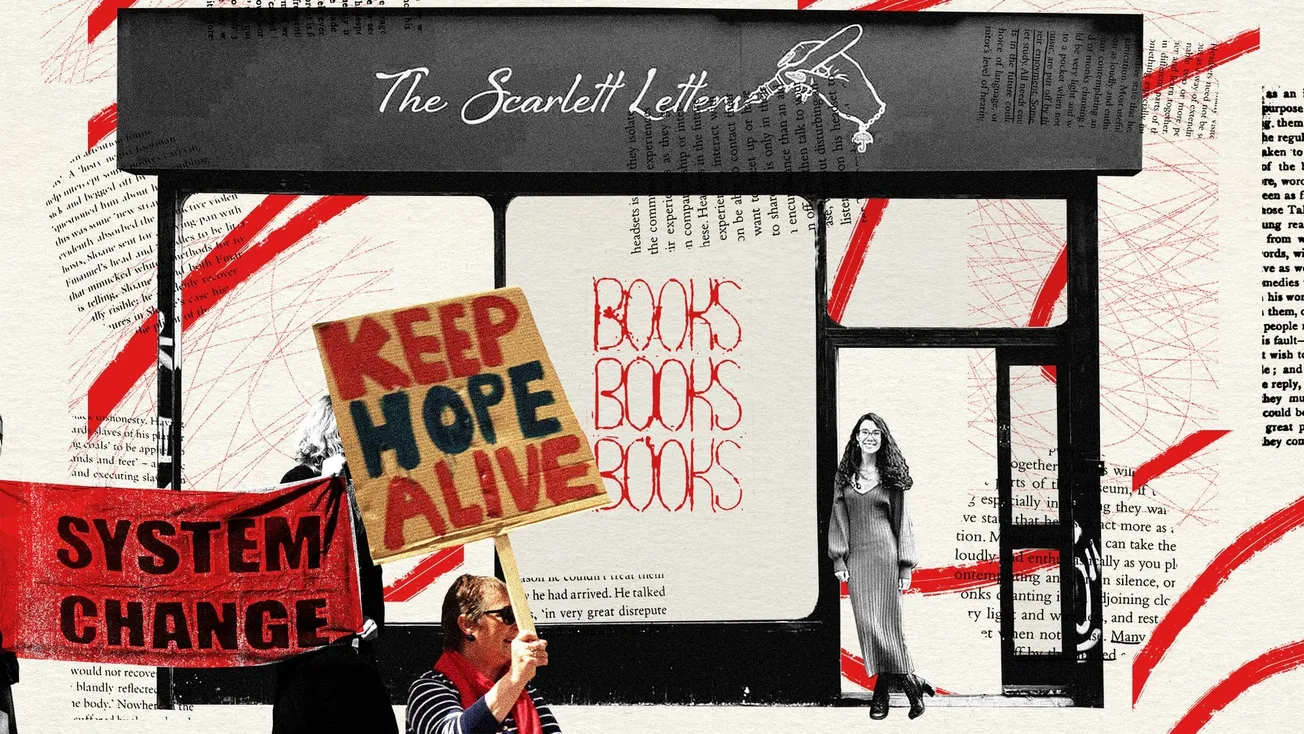

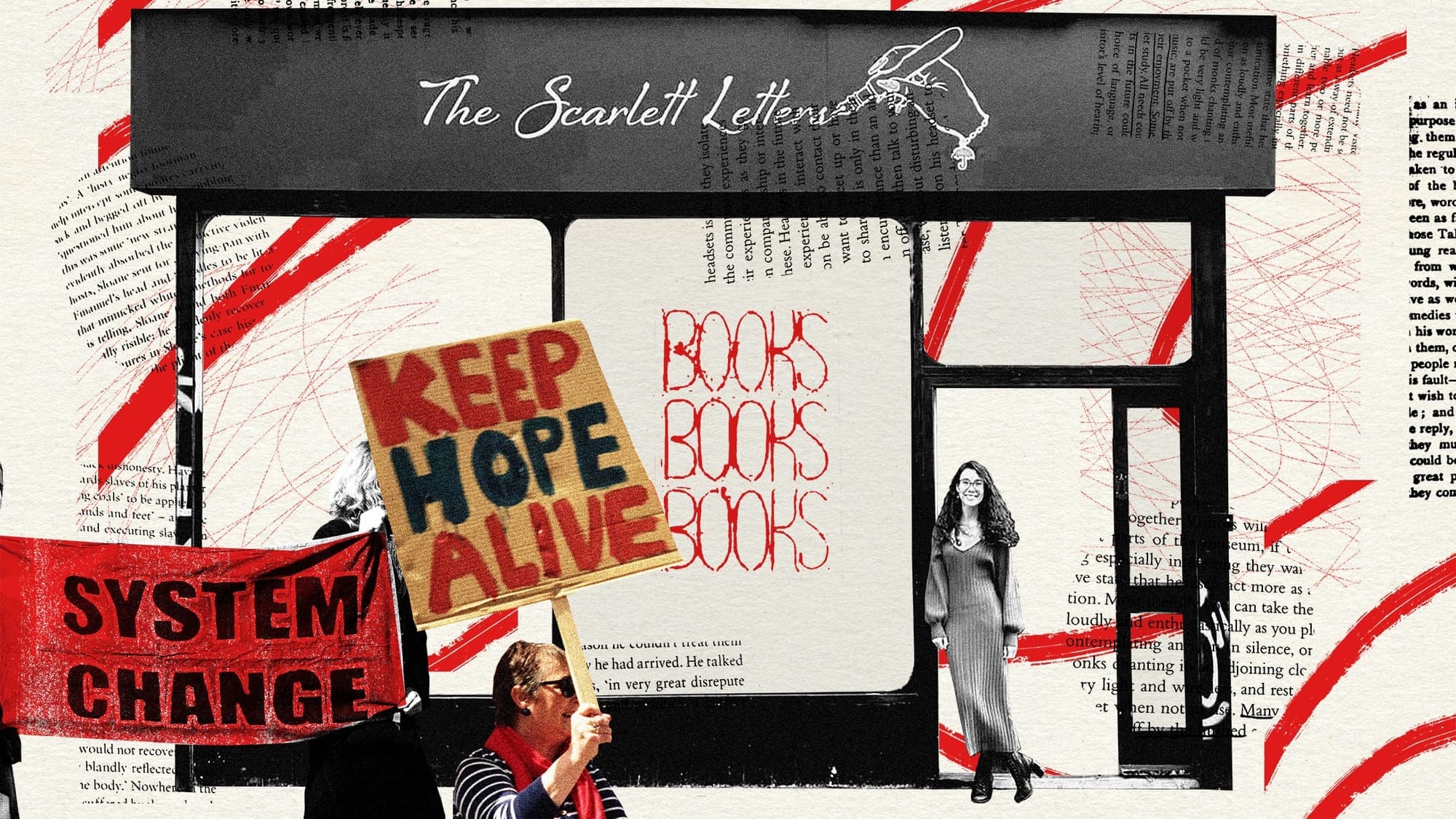

Dozens of people hurriedly packing books into boxes and unscrewing bookshelves. Amongst the torrent of people, maybe the strangest thing they noticed was the face of Blaise Agüera y Arcas: author, AI researcher and the vice president of Google’s research arm. Peculiar though it was to see one of the most senior staff at one of the world’s biggest tech giants busting into a bookshop occupation in Bethnal Green, maybe what was more peculiar was how it all came about in the first place. The setting for this bizarre scene was the Scarlett Letters, named for its owner Marin Scarlett, a radical east London bookshop that was greeted with widespread fanfare by many of the capital's left-wing activists.

And here Scarlett was, with a team of people, bursting into the bookshop in the middle of the night in an attempt to disrupt an occupation by a radical cohort of the shop’s staff. To Parker's mind, for a project started with the aim of platforming sex workers and being a “hub for resistance, community, stories and imagination” to have reached such a point was mortifying. How had things gotten so bad? Well, at least in Parker's telling, it started with a clogged toilet.

Sporting a black T-shirt, cropped hair and anticapitalist and LGBT-rights tattoos on each arm, the former bookseller meets me in the bare, debris-littered unit that used to house the bookshop. We’re here to talk about the whole sorry saga of Scarlett Letters — the rise, the fall, the union disputes, the rows, the occupations and the drilled locks under nightfall. But first, we need to talk toilets.

On a fateful day in early April, less than six months after the shop opened, a plumber had to be called in to fix the disabled toilet, which was inexplicably installed in the non-wheelchair-accessible basement of the bookshop. After the plumber was done, staff opened the work WhatsApp chat to see a message from Marin Scarlett updating the shop’s toilet policy: “We have had an issue over the last few weeks of people just letting themselves downstairs to use the toilet. Our toilet is there for people to use on request, but it is a problem if someone feels they can just let themselves down there without asking.”

Keen to thwart any further opportunistic toilet-users, Scarlett had a new policy. Staff were to personally escort anyone who asked to use the toilet to ensure they didn’t steal any stock or snoop around the staff area. She then told her staff she wanted to “role play” some scenarios in which they could practice saying “no”. Seemingly, the crux of the toilet problem was that they were simply too kind, too feminine, too British: “You are all extremely nice, assigned female at birth, in customer service, mostly British etc., and all of this sometimes doesn't lend itself to ‘no,’” the WhatsApp message explained. She suggested staff had been failing to tell customers “no” when they asked to borrow scissors or mugs from the shop, to come behind the counter or when they wanted to serenade them without prompting.

Like a toilet with a burst pipe, “toilet-gate” then erupted. Almost immediately, a dispute broke out in the work WhatsApp over the message; there was anger not just about that final message, which Parker saw as “bizarre and sexist”, but over the political ramifications of making members of the community ask to use the toilet in the bookshop.

While there had been rumblings of unease from staff for months at the store over the lack of shifts, sick pay and secure contracts, something changed in that moment. “We hadn't broadly discussed unionising with everyone,” explains Parker. “But I saw this, it was like we were in complete solidarity. We needed to unionise immediately.”

Unionisation at a place like Scarlett Letters might sound a bit strange. It was, after all, billed as a radical left-wing bookshop, not generally the sort of place that should need unions. Even the union was a bit confused. “I was a bit surprised when they contacted us,” explains Matt Collins, an organiser for the United Voices of the World trade union.

But within a week of “toilet-gate”, every single member of staff at the shop had joined the UVW. They drafted a list of demands, which included being granted sick pay, an end to the use of zero hours contracts and running the shop on co-operative principles (in other words, allowing staff to have a say in management). It was sent to Scarlett at the end of April. An initial meeting between Scarlett and the UVW yielded some agreements, though Scarlett told the meeting she was working six or seven days most weeks, and was earning less per hour than the booksellers, so needed to hire a manager, a move that would mean several of the booksellers would need to be let go.

Then there was the tricky business of the bookseller’s call for a co-operative management model. Since opening, the Scarlett Letters hadn’t made a month-by-month profit, but had been kept afloat by savings and a monthly donation of £10,000 from an anonymous “angel investor”. Only Scarlett knew the identity of the investor and she shared a response from the investor that they were considering cutting or even pulling their donation if the shop became a co-operative.

With the dispute at something of a stalemate, the booksellers reached for the most obvious lever available to them, unleashing a broadside of Instagram posts in Scarlett’s direction. A newly launched account said they were in “open dispute” with their employer over the threats to fire staff and the failure to meet all its demands. “The workers are queer, trans, racialised, disabled, sex workers and students,” it argued. “Their identities have been used to advertise and fundraise for the bookshop as a radical space whilst their voices are not listened to.” As might be expected, there was an outraged response online. Responses on Instagram accused the bookshop of being a “marketing campaign” as well as “colonial”.

Eight days later, Scarlett fired back on the shop’s Instagram, claiming they had attempted to, or were in the process of meeting, almost all the union’s demands. “Trying to create a space like this in advanced capitalism is extremely difficult,” it read. “The management targeted by this dispute is not a faceless collective of executives in boardrooms. It is one person, who is multiply marginalised, a known member of the community and for the past year has been working for six or seven days a week for the fraction of the salary offered to the booksellers.” It ended with a shocking revelation: the bookshop would now be closing. A meeting with an external HR firm was scheduled for the end of June to discuss the closure and the staff’s redundancies. Scarlett herself said she was surprised at how things escalated and insists she “sent requests to meet again four separate times,” but that “these were ignored or refused”.

And that might have been that. A sad, if fairly run-of-the-mill tale of how an unfortunate toilet clogging thwarted Bethnal Green’s heady dream of a radical bookshop. But that’s not how our story ends, because the soon-to-be jobless booksellers weren’t giving up that easily. In response to Scarlett’s decision, they hatched a plan: they were going to occupy the bookshop.

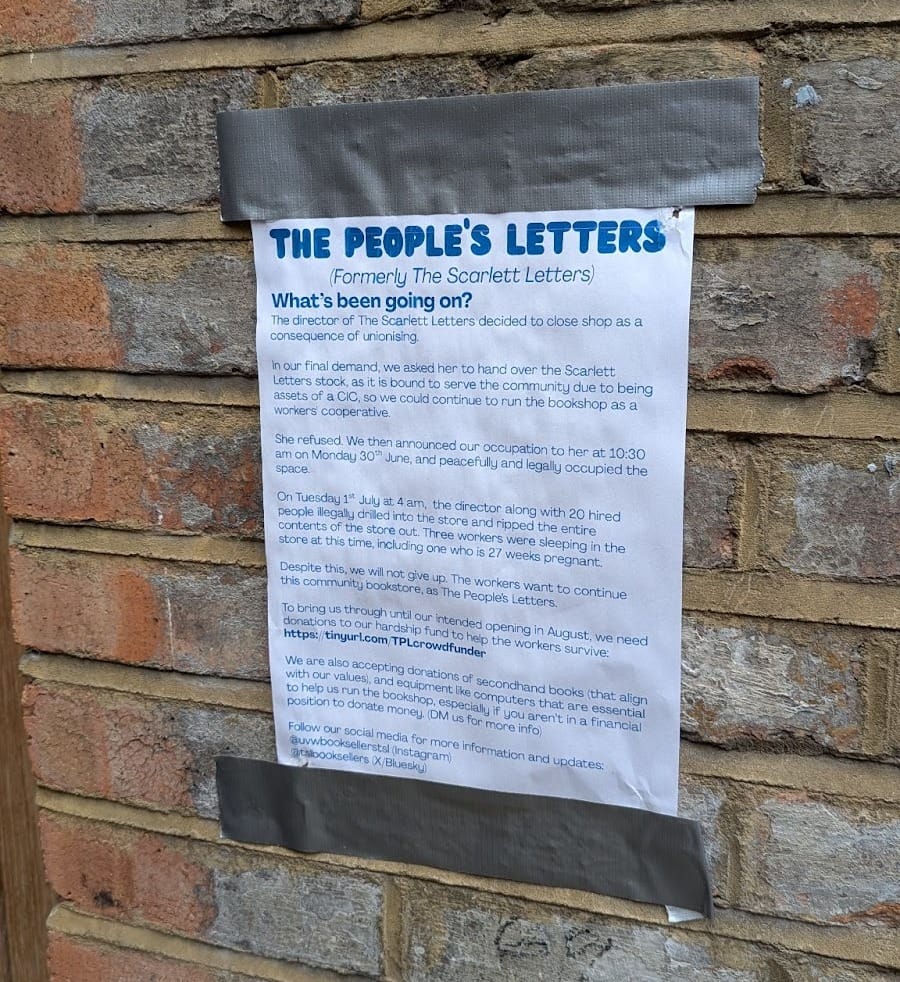

Parker is keen to state that they weren’t aiming to make Scarlett hand over the directorship of the shop, rather they wanted her to donate them the stock. Estimating it to be worth £70,000 (Scarlett puts this figure at closer to £10,000) they felt they could use it to start a new bookshop more closely aligned with their political values.

On the Sunday ahead of the meeting, the staff moved themselves into the crammed two floor bookshop. Parker came with a suitcase, planning to spend four days there. “I didn't have enough money to keep getting the train back and forth from Wimbledon,” they explain. “So I figured that I'll just put myself on the rota for four nights. I was getting a small payment from a porn site that wasn’t a significant amount of money, but enough for the train home.”

On Monday, they joined the video call on one computer, sitting as a group with the shelves of the store as their backdrop. The meeting would last just a few minutes. They made their demand for the stock to be transferred to them. The official from the HR firm explained, on behalf of Scarlett, that the bookshop’s legal obligations meant the books were “asset-locked” and that there was no legal mechanism to transfer stock to employees for free. As the shop’s director, Scarlett could even be liable and struck off starting a company if she did so.

But the booksellers didn’t waver. They announced they would be occupying the shop until their demands were met, and abruptly left the call. Next, they hurriedly unfurled a banner announcing the occupation across the storefront. They had the only set of keys, Parker told me, so thought that as long as no-one allowed management to access the building they could stay indefinitely, protected by squatter’s rights.

By 10pm that night, the three occupiers who volunteered to stay overnight went down to the basement and bedded down, steeling themselves for the weeks of resistance to come. In the end, it would be much shorter than expected.

What the group hadn’t accounted for, was the foresight of Marin Scarlett. As it happened, on the first day of the occupation she had arranged a locksmith, as well as a team to help her recover the stock. She’d covered every base: even hiring carpenters to remove the bookshelves and bringing along three legal observers to impartially oversee things. At around 4am, they arrived at Scarlett Letters and started drilling.

Over the next three hours, books were slid into boxes and shelves were unscrewed from walls. At some point in the night, Parker emerged up the stairwell and saw the whole sorry scene play out. “There were people I knew personally, and that just horrified me,” Parker says.

Now, the bookshop is a husk, almost entirely empty apart from the posters announcing future plans to reopen as “The People’s Letters” — a co-operative run by the booksellers that they believe will adhere to more leftist principles than its predecessor.

Unsurprisingly, Scarlett sees the whole debacle quite differently to the booksellers. She says she “had hoped to work with the union” and that “an improved sick pay was immediately implemented after our first meeting with UVW”. When the talks with the union broke down and things were taken to social media, sales tanked and it became clear that the store couldn’t stay open. The “shop would have stayed open until late July had the booksellers not tried to steal the stock, but their actions forced us to close several weeks early”. When she and a group of friends entered the shop to reclaim the books, they “did not know that anyone was in the property when we entered”.

Collins has spent 14 years in the trade union movement, but is equally baffled by how things managed to end where they did. “I've never experienced a dispute like it before,” he tells me. “I imagine I never will again.” Here ends the tale of Scarlett Letters, the radical bookshop the capital could have had, only for those dreams to be flushed away.

Welcome to The Londoner. We’re the capital’s new magazine, delivered entirely by email. Sign up to our mailing list and get two totally free editions of The Londoner every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and an in-depth weekend piece like the one you're currently reading.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.