If you haven't already, you can become one of our founding members by subscribing to The Londoner with our forever 20% early-bird discount. Click here to forever get an annual membership for the discounted price of £71.20, or click here to forever get a monthly membership for £7.16. Hurry though — this offer lasts only until the end of April.

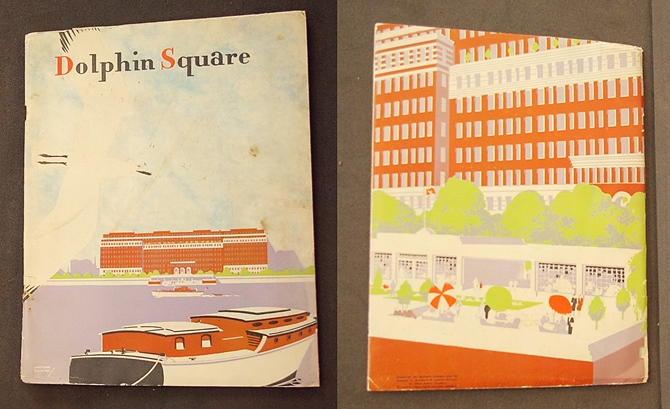

Dolphin Square is changing. Those hulking, monolithic apartment blocks built on the banks of the Thames in Pimlico, rarely mentioned in headlines without the adjectives “notorious” or “infamous”, are undergoing a multimillion pound renovation aimed at rejuvenating them, and perhaps their reputation, as they approach their hundredth birthday in 2038. The timeframe for the modernisation gives some indication of the scale of the buildings: it is estimated that work on the 1,250 apartments will take eight years, only six years longer than it took to build them in the first place.

Perhaps the new work will return some lost vibrancy to the once-upmarket estate; despite the scale of the place (for over 60 years it held the largest number of residential units under a single roof of any building in Europe) it has, in recent years, become a quiet, slightly dilapidated oasis in the corporate blankness of Westminster. Its gardens are neat but dated, with chestnut trees lining a central path towards formal gardens of roses, and a tasteful if uninspired pond where a sculpture of three dolphins twists around a small fountain. Its blocks, each named after a great British admiral, stand facing each other like vast cliffs of brick. Inside, the public areas feel slick with aspic and formaldehyde, a remnant of a past age whose glamour has long faded, chipped and been papered over. A little shopping arcade houses a cafe selling cups of tea and sandwiches, a hairdresser’s doing last minute dos, and a newsagent’s stocking a history of the development written by disgraced Labour MP Simon Danczuk.

Disgrace seems to haunt Dolphin Square. Perhaps it is the very unprepossessing quietness of the place that has led to its reputation as a den of establishment iniquity and vice. Disgrace follows on the failure of discretion, after all, and its location so close to the heart of the British establishment has long made it a favoured home for the pieds-à-terre and grace-and-favour apartments of the nation’s elite. If power corrupts, then Dolphin Square seems to have been corrupted absolutely, from Lord Sewel, secretly filmed in an apartment in 2015 allegedly snorting coke and partying with sex workers, to resident party girls Christine Keeler and Mandy Rice-Davies, whose involvement in the Profumo Affair contributed to the Tory government’s defeat in the 1964 General Election.

The estate’s most serious and disturbing link to crime, however, came with accusations that, throughout the 1970s and 80s, it had been home to an elite paedophile ring of high-ranking MPs and peers.

A major police investigation into the allegations was dropped when it was revealed that the accuser, Carl Beech, was a fantasist and sex offender himself, and was later jailed for perverting the course of justice and child sex offences. If Beech’s stories were once deemed credible — and the Metropolitan Police were certainly sold, for a time — it might be because Dolphin Square’s history is so deeply entangled with secrecy and fiction. Sometimes it feels like no story that comes out of the place is not credible; its quiet hallways seem built for subterfuge, lying and sex.

One of its earliest residents was Maxwell Knight, a deeply strange man who had two great loves: espionage and birdwatching. Knight epitomised the dark side of Britain’s love affair with eccentrics. Eccentric he surely was, but less a harmless kook than a deeply disturbed and unpleasant bigot, a homophobe and an antisemite whose personal obsessions and paranoias, like J. Edgar Hoover in the USA, led him to become a powerful and undemocratic force in the shaping of domestic politics.

In the aftermath of the First World War, Knight, a former naval officer, entered into the loose groupings of far-right politicians, ex-military personnel and businessmen who were attempting to suppress left-wing organising and trade union activities. After working for the Economic League, he joined the British Fascisti, a new political party which mixed an admiration for Mussolini with an ideology developed from British conservative politics, and whose members included William Joyce, the future state-asset-turned-traitor who would become known to the world as Lord Haw-Haw. Knight attracted the attention of the party’s leader (incidentally, the first woman to found a political party in the UK), the chaotic, hard-drinking lesbian Red Cross commandant, Rotha Lintorn-Orman. Lintorn-Orman appointed him director of intelligence for her fascist party, and Knight developed a well-oiled, if amateur, intelligence network across the British far-right.

Seeing how effective Knight had been in infiltrating and monitoring the trade union and communist movements, MI5 recruited him into their ranks, where he took charge of hunting down political subversives. From MI5, Knight waged a secret war on the Communist Party, recruiting spies from across the British far-right — although some, like Guy Burgess and Kim Philby, would later turn out to be Soviet double agents. In 1937, shortly after the start of his second marriage (his first had ended with his wife’s suicide), he moved into Flat 308, Hood House, at Dolphin Square. His wife didn’t move with him: Hood House was very much both Knight’s office and his playground, and as his organisation grew, so did his territory. Eventually, MI5 offices could be found in Rodney House, Keyes House and Nelson House at Dolphin Square.

Knight’s life of deception ran deeper than mere national defence. Despite his overt bigotries, he nonetheless developed a long friendship with the communist gossip columnist, Labour peer and promiscuously homosexual Tom Driberg MP, meeting regularly to discuss Communist Party realpolitik, Westminster gossip and the works of the occultist Aleister Crowley (Driberg was a friend, Knight an admirer). But even the real reason for their rendezvous was concealed; according to his agent and friend Joan Miller, Knight was “sexually besotted” by Driberg. Unfortunately, it wasn’t mutual. In his autobiography, Lord Boothby once claimed that Driberg “once told me that sex was only enjoyable with someone you had never met before, and would never meet again.” Knight would come to take the same approach, advertising for sex with working class men under the guise of requiring mechanics, by Miller’s account.

While Knight would go on to become a prolific writer of both natural history and detective fiction, he is largely remembered today thanks to one of his agents, a future spy novelist he recruited from his Dolphin Square HQ. That writer was Ian Fleming, who took the codename Knight used — “M” — as the name for his fictional spymaster. Knight’s flat at Hood House would inspire other legendary spy novelists, too. In his best-selling novel The Spy Who Came in from the Cold, author and former MI6 agent John le Carré has his hero Alec Leamas meet his Soviet go-between, Ashe, at the latter’s safe-house in Dolphin Square. The flat is small and underwhelming, a reflection of the limp, lonely character of Ashe himself, another homosexual, another member of the Communist Party, and another low-ranking KGB agent. Later in his life, le Carré would move another of his agents, Peter Guillam, into 110B Hood House.

The choice of this particular building to be the safehouse of Cold War agents is a typical le Carré flourish, the kind of elision between fact and fiction that makes his work so compelling. 807 Hood House was, in fact, the real life home of John Vassall, a minor civil servant who had been passing secrets to the KGB for almost a decade before he was arrested in 1962, just a year before le Carré published The Spy Who Came in from the Cold. In 1952, Vassall was posted to the naval attaché in Moscow. As a single gay man, he felt lonely and isolated amongst the diplomatic staff, and soon found himself invited into the underground queer Soviet scene, where in 1955 he was caught, drunk, having sex with a group of Russian men by a KGB sting operation. This, at least, was his excuse for treachery, although he would go on to be paid handsomely by the Soviets as he ran information to them via a London handler for years.

In the end, it was not so much the counter-intelligence agencies who caught him, but Dolphin Square itself. Colleagues of Vassall, who drew a modest salary as a minor civil servant, began to wonder how he could afford a well-appointed flat at a prestigious address whose residents, over the years, have included Charles de Gaulle, Harold Wilson and Princess Margaret. His spending confirmed existing suspicions and, once he was uncovered, the story became national news. Breaking at a time when newspapers and television were first beginning to openly discuss homosexuality in the decade between the Wolfenden Report, which recommended that law criminalising gay sex be reformed, and the 1967 partial decriminalisation of male homosexuality, the news helped fix in the public mind a link between sedition and queerness. Even Leo Abse, the sympathetic Labour MP who helped push through the liberalisation of laws on same-sex activity, stated that “treachery is uncomfortably linked with disturbed homosexuals unable to come to terms with their sexual destiny". With friends like these…

One might argue that given the sheer number of units housed in Dolphin Square, its lifespan stretching across a century, and its proximity to the heart of the nation’s elite institutions, it was perhaps inevitable that it would feature its fair share of stories of geopolitical intrigue and illicit sex. Perhaps. But spend any time in its gardens or halls and it feels like homosexuality and espionage are almost integral to the structure of the building, like the pernicious creepers of history’s garden, penetrating the brickwork and undermining its integrity. Its unique and queer history, in every meaning of the word, suggests that the nation’s story is less upright, more complex and more interesting than it might tell itself. It will take more than a fresh lick of paint to cover it up.