Welcome to The Londoner, a brand-new magazine all about the capital. Sign up to our mailing list to get two completely free editions of The Londoner every week: a Monday briefing, full of everything you need to know about that’s going on in the city; and a high-quality, in-depth weekend long-read.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get our unique brand of local journalism straight to your inbox.

It was almost like fate. Oli Carter-Esdale had spent untold hours as a teenager in The Trafalgar, a historic backstreet pub near Colliers Wood, South London. It was a place, a “community”, that left a permanent imprint; even as they left the city for Bristol, or started managing pubs in Bethnal Green, The Trafalgar was always there, packed into a little unchanging corner of their mind. “I always joked that this was the place; that if it ever closed, if it ever came up for lease, that would be the sign to quit your job,” they recall. “And then it came up.”

Since taking over two years ago, it’s become a thriving and award-winning pub. If you can imagine the platonic ideal of a beloved local pub, but with a modern twist, you can see The Trafalgar. A big part of the atmosphere is Carter-Esdale: with curly ginger hair, a long beard, wire-rimmed glasses, black eyeliner and they/them pronouns, they aren't the image you associate with your stereotypical historic pub landlord. And the venue’s cheap prices (mostly sub £6), craft beers and subtly gender neutral toilets, alongside hundred year-old fixtures and fittings, are an indication of Carter-Esdale’s approach. A pub that cherishes the history that bleeds into every chair and table, every pane of its stained glass windows, while still managing to adapt. “There’s magic here. I don’t know if we built it or if we inherited it,” they explain. “What I exist as now is as a steward of that.”

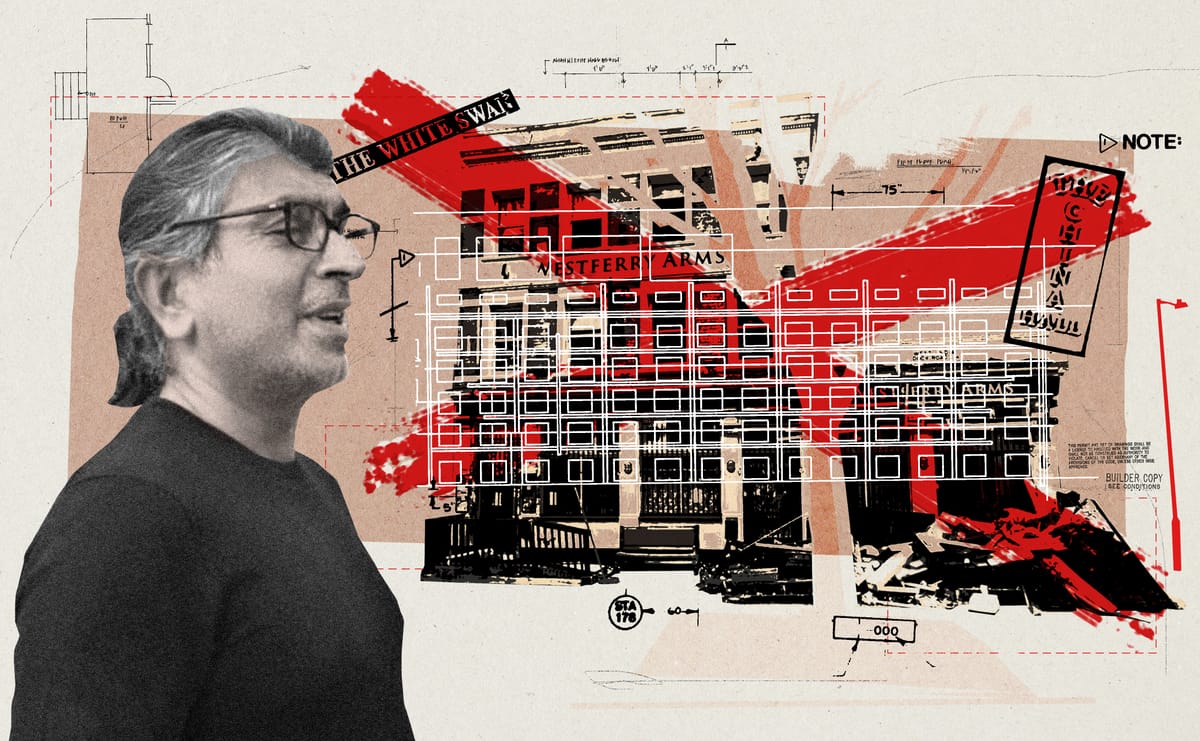

But the pub is in the fight for its life, facing demolition at the hands of a Finchley-based development company called Linea Homes. The pushback from the hundreds of locals who worship The Trafalgar, at a scale, frankly, I’ve never seen in my time reporting on pubs, has meant the dispute has escalated to a national planning appeal. Linea claims that its plans — to demolish the building and replace it with six “high quality” flats atop a commercial space that could be used as a pub — are the only way to keep The Trafalgar at the “heart of the community” and “secure its future”. It’s a common refrain from the company, which claims it is now the “go-to pub buyer” in the UK property industry. In public posts and messages on LinkedIn, they talk about how they “love a boozer” and “have recently acquired a number of pubs and brought them back to life by maximising the surplus space above and around the pub, using the proceeds to invest in the core business to ensure the long term viability of the community asset”.

Despite selling themselves to the public and pub landlords as saviours, the firm, and its co-owners Anthony Stark and Gavin Sherman, are one of the most controversial pub redevelopers in the capital. By speaking to pub landlords, trawling through Companies House filings and analysing brochures made by Linea Homes for prospective customers, we have identified at least 28 pubs in the capital and its surrounding area that have been bought by Linea and its directors over the last decade and a half. Eighteen of those are now permanently closed, with just a handful narrowly escaping redevelopment, including some of the capital’s most popular pubs, like The Montpelier in Peckham and The Golden Lion in Camden.

A spokesperson for Linea told The Londoner that the “reality is more complex” than “profit at the expense of community”. “Without careful investment and adaptation, many pubs close outright. That outcome is far more damaging than responsibly designed schemes that allow them to evolve and remain relevant.”

The vanguard of gentrification

“I’m basically the local kid who came home,” Carter-Esdale tells me. They recall taking over the lease of the pub after it was put up for auction to find the place in complete disarray. The basement had soiled mattresses and pillows, there were axe holes in the walls, piles of stuffed bin bags filled the garden and, strangest of all, oil stains marred the pub’s main room, seemingly from motorbikes stored and repaired in the venue. For months, Carter-Esdale worked 90 to 120 hours every week, first to get the pub into good enough shape to open by September 2023, and then behind the bar while it was still in its early days. It’s not their only pub — they opened the less-endangered Hand and Marigold in Bermondsey six months ago — but the sheer amount of sweat and blood that went into reviving The Trafalgar makes it stand apart. “This is always going to be my top pub,” they explain. “My head is up there, but my heart is down here.”

Soom after after taking over the pub, the first planning application went in for its demolition. Carter-Esdale was blindsided. “I just thought: fuck this, I’ve sunk £35,000 of my own money, god knows how much of my time and all the rest of it,” they recall. Then another application hit in June 2024. That led to them, and the locals, declaring war; over 400 objections were submitted to the local council, they tell me. Facing unprecedented community uproar, that proposal was rejected by the Merton Council in May, only for it to be appealed by the developer to the planning inspectorate, leading to the national planning dispute the case is stuck in now. Carter-Esdale notes that Linea’s appeal to the planning inspectorate argues that the firm “sees no reason why the sociocultural characteristics” of the historic pub “would not be carried over to the new space”. “You have to be so thick headed to think that something intangible is transferable,” argues Carter-Esdale. Currently, no-one at The Trafalgar has been given any indication as to when they can expect a ruling in their case, though the average for a case like theirs is usually just over six months.

“I see Linea Homes as the vanguard of gentrification… They see a cultural asset and they think, let’s rip it out, carve it up into tiny pieces, and turn it into a thing that makes us a profit,” they say, enunciating every word as an uncharacteristic rage overwrites their usually soft-spoken demeanour.

Carter-Esdale has never met Anthony Stark or Gavin Sherman. Their interactions, the exchanges that now hold The Trafalgar’s future in the balance, have been limited to signed contracts, rent payments and desperate written appeals mediated by council committees. But a publican named Shane Ranasinghe vividly remembers the exact moment he met Stark. It all started with a phone call, and a mysterious visitor.

The tale of The Montpelier

Ranasinghe is one of the co-owners of The Montpelier in Peckham. The pub is part of Parched, an upstart pub group run by Ranasinghe and three long-time friends that now manages seven community pubs across South London, including The Grove House Tavern, The Roebuck and The Earl of Derby. In 2010, they took over The Montpelier in Peckham, with a lease that would keep them there until at least 2020.

Within a year, they got a call from their freeholder telling them a surveyor would be coming around to assess the property. “I knew he wasn’t a surveyor, because of what he was looking at,” recalls Ranasinghe. “He wanted to look outside, look at the elevations, and see how many rooms he could squeeze upstairs. It was all a bit off.” While the man avoided answering most of Ranasinghe’s questions, he did reveal one thing: his name was Anthony Stark. After he left, Ranasinghe put together that Stark was a property developer, and it dawned on him that the pub might be getting sold.

Know of any other stories similar to this? Let us know using the anonymous form below or email our editor.

Just days later they got a visit from a company called Paramount, who claimed the pub was now for sale and they were handling the process. The man in charge? None other than Gavin Sherman, Stark’s soon-to-be business partner at Linea Homes. A ‘for sale’ sign was hastily added to the building, and just as hastily removed days later when the friends were told that the property was sold to Stark.

The new owner came around for a ‘formal’ inspection. Ranasinghe describes how Stark and an associate walked around the pub and its upstairs discussing its development value, largely ignoring his frantic questions about the future. In that moment, he felt it was clear the new freeholder wanted them to leave.

It became even clearer with the beer. The Montpelier was a “beer tied” pub at the time — rather than paying all its money in rent, it also had to buy any beer it wanted via its freeholder, at whatever price they wanted to set. And Stark’s management company decided to change what beers they were allowed to order; the craft beers and local breweries that had been the Montpelier’s trademark were gone, replaced with cheaper lagers like Fosters, but supplied at a much higher price. Soon after, their insurance payments to Stark also shot up.

Then came The Montpelier’s rent review. A burly surveyor working for Stark visited the pub and took Ranasinghe down to the basement. “He said ‘I'm here to do your rent review, but it's not looking good for you guys… you need to get out of here fast. And if you don't, you're done’,” he recalls. Stark subsequently told the Parched team that key paperwork arranging their current rent had inexplicably disappeared, invalidating their current rent rate. As a result, Stark wanted to more than quadruple their current rent to well over £100,000 a year (plus the “wet rent” of their tied beer) and backdate those costs to 2005. He also submitted a list of purported defects in the pub — including things as tiny as cracked paint on a windowsill — they would have to fix. All in all, it would have created an immediate debt of some £200,000, enough to “destroy” the pub, and force Parched to forfeit their lease. Ranasinghe concluded that the goal was to redevelop the property.

In the end, Parched managed to take Stark to a formal rent review, stopping his planned increase and retroactive billing, and found other ways to make running the pub a “ballache” for the developer, as Ranasinghe puts it. After years of refusing offers by Stark and Sherman to buy out the lease, the developers decided to sell the property to its current owner, who has invested in the pub, allowing The Montpelier to grow into the community institution it is today.

Sorry to interrupt. We just wanted to take you behind the scenes. Journalism like this is old-fashioned, boots on the ground stuff. We send our writers out into the city, away from their laptops, to be where the events they're covering are actually happening.

This sort of in-depth journalism doesn't come cheap. This is why it's getting rarer. A lot of media companies have given up on it, instead churning out clickbait articles that have little connection to local areas. But we believe people are still willing to pay for deep dive, properly reported work.

Already, well over 850 of you have signed up as paying members to prove us right. But now we have a big target: 1,000 members. We've made it easy too: with our summer discount, a Londoner membership is just £1.25 a week. That's less than a daily coffee.

We don't rely on billionaire oligarchs, or huge companies to fund us. We just need the people of London and beyond. If you like what we're doing, please consider supporting us.

As Ranasinghe relived his nightmare, there was a niggling sensation I couldn’t escape. I had heard this story before.

“The grim reapers of the industry”

Parched’s experience was almost identical to that of The Golden Lion in Camden, as recounted to me by its then landlord, now owner, Dave Murphy. In 2011, he too heard a rumour that his freeholder — the same company that then owned The Montpelier — was considering a sale. Like The Montpelier, they soon received a visit from Anthony Stark in the guise of a surveyor. Not long after they too found out that the visitor in question had bought the pub in a deal that was also brokered by Gavin Sherman, as director of Paramount. Once the takeover went through, they also faced sky-high beer costs and huge bills.

Enjoying this edition? You can get two totally free editions of The Londoner every week by signing up to our regular mailing list. Just click the button below. No cost. Just old school local journalism.

Maybe the only difference was that in The Golden Lion’s case, Stark and Sherman actually got as far as submitting a planning application to shutter the pub and convert it into luxury flats. In their lengthy submission to the council trying to justify the pub’s lack of community importance, they described the venue as “unlawful, inflexible, inaccessible, unsafe, insecure, inconvenient, and generally unsustainable”.

Murphy managed to win his planning battle. He took over the freehold himself in February 2015, and the pub sits on its Camden street corner as a proud survivor. Not least because just less than 500 metres away another pub called The Parr’s Head had been shut down after getting taken over by Stark and Sherman. “They’re the grim reapers of the industry, they’re not its bloody saviours,” Murphy tells me. “And for them to claim that is an absolute insult.”

The whole saga was covered by The Guardian at the time. But it was far from a single case. While looking into Stark and Sherman, we found a portfolio on the Linea Homes site for prospective customers where the firm describes how it is “especially keen” to buy pubs as part of their mission to build “luxury flats”. They also list their past success stories, which includes some 28 pubs in and around London and many more in Bristol, Oxford, Northampton, Leeds, Peterborough and Sheffield. Some had only been partially redeveloped — like The World’s End in Finsbury Park or The Huntsman and Hounds in Walworth — or risked closure but survived like The Montpelier and The Golden Lion.

The majority of those pubs though, including the eighteen in London, have been permanently shuttered, usually replaced with blocks of luxury flats. A small number, including The Trafalgar or The Victoria Tavern in Plaistow, are facing up to the same fate, though The Trafalgar seems to be only one fighting back. In 2010, Sherman reportedly told the Property Drum magazine that as few as 10% of pubs sold on to developers remained pubs. During a podcast interview in 2021, he said he had been involved in as many as 700 pub sales across his career.

We first started looking into this story after publishing an investigation on London billionaire businessman Asif Aziz and the companies linked to him, which we revealed had been behind the closure of over two dozen pubs across the capital. Our exclusive, which involved trawling through corporate records and planning documents, has been one of our most read stories of the year. We’ve since received dozens of tips, including one from a reader with concerns about the plans to shutter their local — The Trafalgar.

Like Aziz, many of Stark and Sherman’s most notorious closures were conducted several years ago. But in the last decade or so new regulations governing cultural venues like pubs — including the ability to get a venue listed as an ‘asset of community value’ — have made redeveloping even empty pubs much harder. In essence, the law now ensures that you have to prove a pub is completely unviable before any development can take place. Those laws allowed campaigners to save pubs initially shut by Aziz like The China Hall and The Old Justice, both in Bermondsey.

But where Linea and its owners differentiate themselves from Aziz is that since those new protections have come into place, they have heavily pivoted their business model away from wholesale closure and redevelopment of pubs to partial redevelopment, something they claim allows them to cross subsidise the pubs. But campaigners tell The Londoner that this approach can result in ‘death by a thousand cuts’: by redeveloping pub gardens, car parks or sections of the interiors, or demolishing historic pubs in exchange for a new unit below a block of new build flats, developers can make the entire business unviable, and therefore a candidate for closure.

A spokesperson for Linea Homes suggested that the account of the Trafalgar dispute described by Carter-Esdale was “one sided” and that “the narrative of ‘developers as destroyers’ oversimplifies and misrepresents a process that, when done responsibly, sustains both heritage and community value”.

They stressed that their plans would deliver “a larger, modernised pub with a proper kitchen and genuinely usable outdoor space, designed to thrive as a genuine community hub” that would ensure the pub’s future. They added that they had made “repeated attempts to engage directly with the pub operator in good faith, but they have chosen not to engage in dialogue.”

“Linea Homes has acquired and developed numerous sites, with a clear focus on brownfield regeneration and the delivery of much-needed homes in such locations. Naturally, these types of projects can spark differing views within local communities about their benefits,” they added. “Yet, the wider reality is the critical shortage of housing in inner-city areas. At the same time, SME house builders face increasing challenges — exacerbated by a struggling planning system and wider economic pressures.”

The bricks and mortar

The longer I sit talking to Carter-Esdale, and hear long impassioned asides about the pub’s history, or watch them share the life stories of the dozens of regulars that walk in (each of whom they know by name), the more I get the sense that there is no line between where the charismatic landlord ends and The Trafalgar begins. Demolishing the pub would be like excising a small part of their soul.

They even credit the pub with them getting together with their wife Alice. The pair — for a long-time nothing more than friends — started spending more time together after Carter-Esdale took over The Trafalgar and she reached out to see if they needed any help. “We got together and I just thought: ‘This is it’,” they recall. “Less than a year after opening this place, we got married.”

After over two hours of rambling discussion, Carter-Esdale ushers me over to meet the dozen or so locals drinking by the bar. I need to properly “understand the gaff”, as they put it. Several pints of crisp understanding later, a thought bubbled up into my mind.

It’s not just that there’s a special sense of community to the pub, one you often get told about but rarely see. But I was struck by the painful fragility of it — the sense that the only thing that kept this eclectic mix of ages, professions and backgrounds together was this specific space. As I walk out of the pub, I think back to one of the comments Carter-Esdale made after recounting some of the decades-old lore of the pub and its regulars. “There's a long line of history that exists here,” they said. “It’s all tied up in the bricks, in the mortar.”

Editorial note 04/10: This article was amended to add an additional statement sent by Linea Homes post publication.

If you enjoyed Andrew's story and want to get sent similar investigations on the city's future, why not join up as a Londoner member today? This means you'll get weekend long reads like our piece on the strange death of east London's radical bookshop and Monday briefings like our scoop on the closure of iconic South London nightclub Corsica Studios delivered straight to your inbox.

No ads, no gimmicks: just click the button below and get two high-quality pieces of local journalism each week, all for free.