Sign up to our mailing list to get two totally free editions of The Londoner every week. Just click the button below. No cost. No gimmicks. Just quality local journalism.

Harry Shukman is a researcher at HOPE not hate, an anti-extremism organisation. His book, Year of the rat: Undercover in the British far right, about an infiltration project into nine different extremist groups, is out now.

I realise I’ve messed up instantly, my hand still stuck out in introduction, the aspirated “H” sound dying on my lips. I was about to say my real name, Harry, but that isn’t what I’m supposed to be calling myself. Today, I’m “Chris”, an enthusiastic recruit to the far right. The member of the extremist group I’m meeting doesn’t seem to notice — I’ve managed to correct myself just in time, hoping the alarms sounding in my brain weren’t visible on my face.

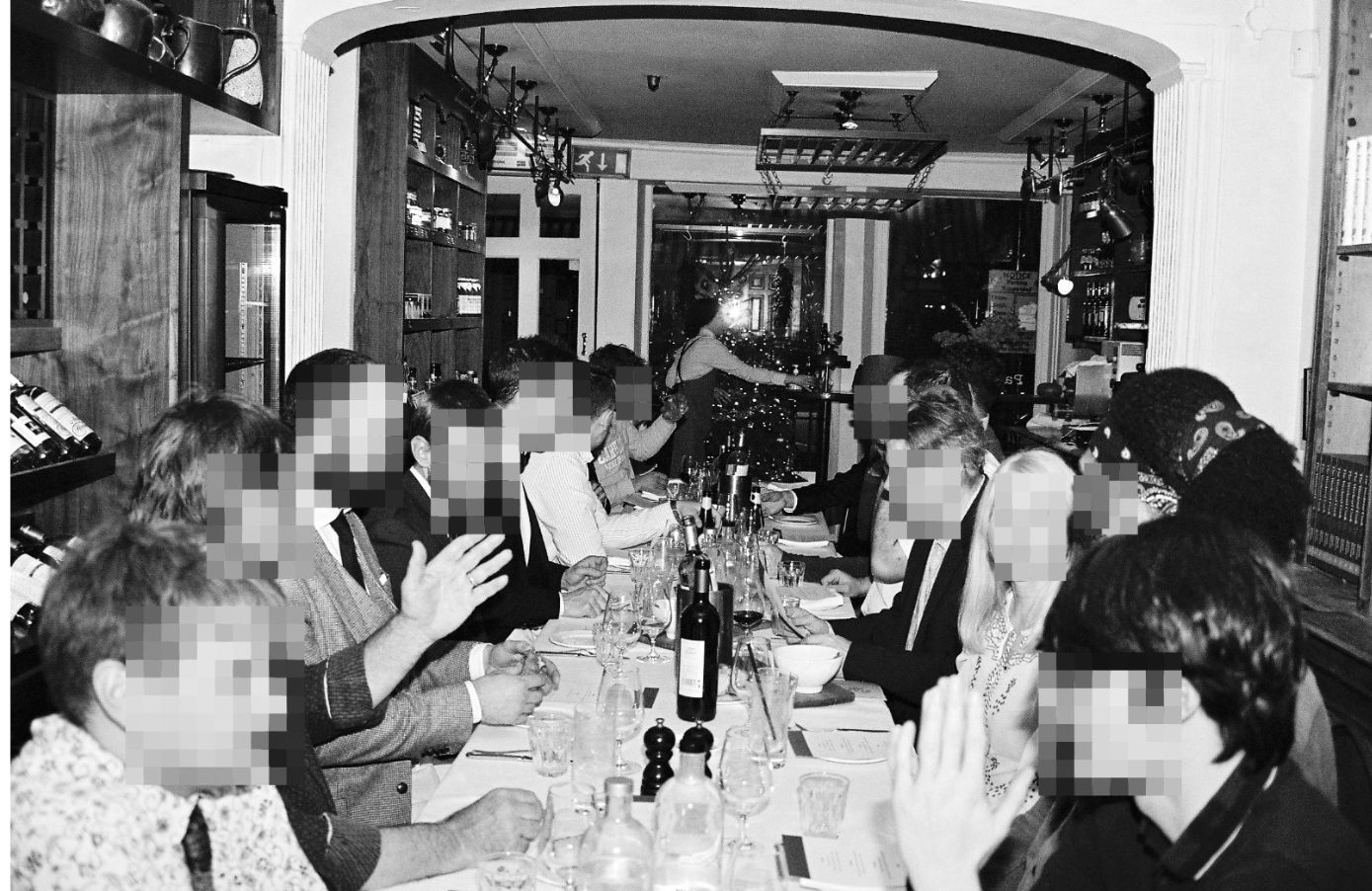

I’m at the Crosse Keys, a massive pub near Liverpool Street that is the meeting place of a strange organisation called the Basketweavers, a network of young, mostly professional men (and a handful of women) dedicated to far-right politics. They have chapters across the UK, with 1,300 vetted members, making it one of the largest far-right groups in the country. As a volunteer for Hope Not Hate, an anti-extremism organisation, I’m embedded inside the London chapter, the busiest one.

Every other Friday, the Basketweavers go to this pub. You’d never guess, slipping past the crowd of hammered City boys, that in this Wetherspoons, the vanguard of the British far right is plotting a victorious future in an upstairs room. But it’s here, over chicken tenders and pints of Doom Bar ale, that the Basketweavers discuss esoteric fascist philosophy and their hatred of the Jews.

Who are the Basketweavers?

The Basketweavers come from all kinds of backgrounds — while undercover, I met delivery drivers, cleaners, and factory floor workers — but the overwhelming majority of them seemed to be young, middle-class professionals. A lot of them had been to university, and a few were still studying. None of them appeared to have enjoyed it much. “All of my university professors were Marxists, Jewish, or worse: both,” I heard one Basketweaver moan. Now they worked in finance, engineering, IT, pharma and the civil service. I got the sense that nobody was that happy in their jobs.

I fitted into the background of all this. As Chris, I pretended to be a corporate drone with a dreary life. If people thought I was dull, then they would pay less attention to me, and hopefully I would avoid suspicion. I lied about having a soul-crushing job as a strategy consultant (with the yawn-inducing brief of support function optimisation). When asked, I said I came from rural Cambridgeshire, from a true-blue Tory family, but had hardened my views after coming to London, whose size, noise and diversity I found bewildering. For ethical reasons, I never wanted to prompt a racist conversation — that would feel like entrapment — but if asked, I would say I was concerned about demographic replacement, the worry that one day white Britons would become a minority.

Our Saturday stories are free for all to read — but we can only produce this kind of work with your help. If you're a fan of today's piece, please do consider becoming a paying member with our new members' summer discount.

In real life, my circumstances were radically different. I had an opportunity to team up with Hope Not Hate in late 2022, when I was a journalist working for Mill Media, The Londoner’s parent company. There, I’d experimented with undercover reporting. The pandemic had brought together two very different demographics: anti-vaccine campaigners (organically-minded former hippies) and far-right activists (lagered-up skinheads who might have once kicked the formers’ heads in). I was writing about this unlikely alliance, sometimes undercover, when Hope Not Hate got in touch about a long-term infiltration, so I said goodbye to my Mill Media colleagues and started my new life as Chris.

Hope Not Hate had become aware of the Basketweavers when they were promoted by far-right YouTubers. One was Neema Parvini, a former academic at the University of Surrey, who has called black people “impulsive and low-IQ”. Another was Keith O’Brien, a monotonous white nationalist who in one video held up an actual woven basket: “Alone these pieces of tree bark are weak, but when brought together, they make a mighty basket”. O’Brien announced the formation of a new group that was “totally apolitical, for people to come together and discuss basket-weaving”. O’Brien has a reputation among the online far right as one of its more hardcore figures. He once called himself “a raging anti-Semite”. If he was willing to endorse the Basketweavers, then they must have been very extreme indeed — and we needed to find out more.

Hope Not Hate’s researcher Patrik Hermansson (who had gone undercover himself in the alt right in 2016 and was at Charlottesville’s Unite the Right rally the following year) and I went through the Basketweavers vetting process. It included a list of questions about political opinions, such as the Covid pandemic and Israel/Palestine. We passed, giving us access to the Basketweavers’ server on Discord, a messaging app. The Basketweavers are more sophisticated than a lot of other far-right groups in that they try to enforce a certain online discipline, and ban members from having racist conversations that can easily be seen by journalists and antifascists. They use their main group chat only to arrange real-life meetings.

With a hidden camera strapped to my chest, and at other times using a voice recorder on my phone, I started going to Basketweaver meet-ups. They release a calendar every month, advertising nights at the Crosse Keys, plus Saturday afternoons at pre-Raphaelite art shows, Sunday morning walks in Otford and an occasional private club event. Every spring, there is a ski trip to the French Alps. While these events might not exactly sound like Nuremberg circa 1936, the Basketweavers don’t see their calendar as entirely social — it’s also political.

Minutes after first arriving at the Crosse Keys, wearing the drabbest work clothes in my wardrobe, a fake lanyard around my neck and my heart in my mouth, I heard members talk about “the JQ”. This is “the Jewish Question” — how to rid Europe of Jews. They also spoke of their admiration for Mark Collett, the head of Patriotic Alternative, at the time Britain’s biggest white nationalist group. Others told me about far-right protests they were attending on the continent, and discussed the need for nations to have a “pure stock”, a bloodline uncontaminated by foreigners. I was surprised that they were so open with me, a stranger, but it probably helped that I had joined the Discord group months before showing up — perhaps they thought I was shy or lazy, rather than someone eager to sneak inside.

Advertising the Basketweavers in 2022: Keith O’Brien, Edward Dutton, Thomas Rowsell (Image courtesy of Hope Not Hate)

The Basketweavers’ cryptic website claims they want to “heal the longing that we have for real human connections”. But to their founder Mark Houghton, who claims to be a qualified psychologist, community means more than just connection. It’s about radicalisation. “Meeting in person will do more for you — will do more for us — than a hundred online Discord sessions,” he said. “It will do more for your thinking, for your social interaction, than listening alone to a dozen podcasts.” He hoped, when he laid out his vision for the Basketweavers in a 2021 speech, that members would bring “a brother or a cousin or simply a friend from work” to events. In real life, potential recruits would be “much more amenable to listening to what you have to say”.

“I consider myself pretty low down on the totem pole of society”

While embedded within the group, I found that what united a lot of Basketweavers was their loneliness. Those who still lived with their parents sometimes described bleak domestic scenes. There was a Basketweaver who lived at home but wasn’t on speaking terms with his mum and dad. Another had been locked out of certain rooms in his house, apparently a punishment for spending his allowance on sex workers. One member said he was proud of arguing with his mum at the dinner table, berating her into silence when they fought about abortion rights. A conversation that still haunts me was with a Basketweaver who believed his romantic prospects were slim. “I consider myself pretty low down on the totem pole of society,” he said quietly. “I spent most of my formative years being rejected by people.”

One busy night in the Crosse Keys, a man named Jimmy* walked in. He was new to the group, and, as he pushed his way through the crowd to find a seat, I thought he was also a journalist. He had the crumpled clothes and dispirited aspect of my former newspaper colleagues — but he said he worked in a tech job. In his forties, he was a little older than most of the Basketweavers. Jimmy told the table about a nasty split from his wife. Why? When their children came back from school talking about art classes designing pride signs, or their history lessons on Nelson Mandela, he would argue with them. He called it “counter-subversion”, and his wife hated it. “It’s why we broke up.”

For Jimmy, wokeness was everywhere. A museum he took his kids to was spoiled by a “multi-culty” exhibit. His office apparently held a lecture on how hard it is for disabled gay men to go clubbing. “They had balloons the colour of the trans flag, and I just thought, ‘Oh my God,’” he said. It was getting late, and some of the drinkers had started to go home, but Jimmy showed no signs of leaving. After six pints, he sounded glum. “I can’t talk to anyone about this stuff,” he said, gesturing around at the remaining Basketweavers. “I feel like I’m really on my own here. I’ve had two intellectual conversations in the last year and both of them were in this room.”

Other Basketweavers told me about their weekdays spent in dreary jobs where they felt distant from their colleagues. They spent their evenings in front of far-right livestreams, three or four hours of YouTube rants about racist philosophy. Any excitement they may have felt on moving to London had now curdled. The friendships and relationships they had expected from life had failed to materialise. Listening to the internet programmes of extremists, they had found an explanation for their disappointment: society is being manipulated at the expense of young white men. More often than not, according to the conspiracy theories they were tuning into, the people pulling the strings were malfeasant Jews.

At another boozy night in the Crosse Keys (by this point, I had learnt to pour non-alcoholic beers into a pint glass to stay alert), I met Kyle*. He looked to be in his late twenties and said he worked in the IT department for an investment bank. He had a large beard and expressed a fondness for a racist American podcaster called the Bronze Age Pervert. Kyle and some of the other Basketweavers got into a conversation about the Great Replacement. This is the fantasy that animates so much of far-right activism, a belief that elites (who typically belong to a certain Abrahamic faith) are coordinating the mass migration of Asians and Africans into Europe to extinguish the white race. Kyle asked the table who or what is causing it.

One of the Basketweavers said it was corporate greed, a desire for cheap labour.

“No, no, that’s not it,” Kyle replied.

“It’s about weakening the stock via miscegenation, making Europe less strong,” said a Basketweaver called Freddie*. His evidence was TV adverts depicting multiracial families. “It’s always a black man and a white woman,” Freddie said. “They’re trying to lay the groundwork for white women to give birth to mixed race babies.”

Kyle asked who was responsible for this propaganda.

“The guys with big noses?” asked a Basketweaver called Joe*.

Kyle nodded. “It’s in the interest of Talmudic forces,” he said. “Jews want us weaker so we are easier to rule.”

“Keep your voice down,” said Joe softly, gesturing to other customers in the pub at neighbouring tables.

Other Basketweavers were convinced that Jews were putting seed oils into processed food in order to weaken white people and make them unhealthy and impotent. Jews, I was told, control the porn industry in order to distract white men from having babies with white women.

Belief in conspiracy theories, according to research, can make people feel more anxious, powerless and uncertain. I thought about this when I saw Basketweavers act in unusual ways. One member told me he anticipated societal collapse and kept fifty jerry cans of petrol in his garage, treating them with a fuel stabiliser. Another told me about how he keeps trying to tell his friends about the Jews. “I have tried to bring up how much they control certain industries,” he said.

Sign up to our mailing list to receive our free Saturday stories, every week.

Untempered cruelty

According to their website, the Basketweavers want to promote meaningful connections, but they also say they want to “promote healthy and positive values” and remove “the fear of reprisal for expressing ourselves”. Towards the end of my time with the network, I wasn’t so sure if those ambitions had been realised. Basketweavers could be shockingly cruel to each other.

At one summer meet-up, I listened with alarm as Robert*, a veteran member, ranted about another Basketweaver: “He’s a twat. He’s a fucking liability. I find him insufferable. I saw him around the street last weekend, and I blanked him. I pretended I didn’t know him. A fucking idiot.” Robert joked about hanging another member “off the ceiling” to “use him as a punching bag”. On another occasion, the guys heard that a Basketweaver had moved overseas. “That man is a dredge upon society,” someone said. “He is first into the gas chamber … I hope his plane crashes, and a fucking mutt dies.” It seemed deeply sad to think that all the lonely young Londoners who joined the Basketweavers in a bid for connection and meaning were being further tormented by their supposed friends in the group.

I heard rich members mock poor ones who couldn’t afford expensive events (the conferences cost hundreds of pounds), and sexually inexperienced men insulted as virgins. One night in the Crosse Keys, a Basketweaver described going vegan to recover from Covid. A senior member interrupted: “Why the fuck did you do that? Was it just ‘following the science’? Did you also start believing in trans bullshit?” Expressions of support for Ukraine or indications of a belief that climate change may, in fact, be real, were met with similar venom. The Basketweavers believe progressive culture stifles debate. I wasn’t convinced they were as welcoming as they thought they were.

“My dream is you can go to any town in the UK, or globally, and have somewhere you can be safe and have resources, like embassies”

Mark Houghton, the Basketweavers founder, said society keeps us in a “constant stress state”. In that speech where he imagined the future of Basketweaving, he said too many young people have poor mental health, are addicted to social media and lack in-person friendships. That’s certainly true. But his analysis of modern life also included, in its list of disadvantages, “the crimes of Islam” and “hypergamous dating”. The latter is a belief, propagated by Manosphere figures such as Andrew Tate, that dating apps have permitted undesirable women to ignore men of equal value in pursuit of more attractive matches.

I finally met Mark at a far-right conference in August 2023. The star speaker was the influencer Michael Wright (aka Morgoth), who has elsewhere defended the Waffen-SS and admiringly quoted from Mein Kampf. Mark told me that the Basketweavers were intended to have a low social and political risk — which sounded like he meant the creation of an easy way to join the far right. “My dream is you can go to any town in the UK, or globally, and have somewhere you can be safe and have resources, like embassies.”

The Basketweavers are now a firm fixture on the British far right. They organise conferences with academic-style lectures at the East India Club and the Little Ship Club. They even helped to organise an art exhibition at the Fitzrovia Gallery (futurist sculptures, paintings of women posing suggestively over sofas). Leaders in the fascist Homeland Party came to one of their summer barbecues, while activists who have been in Patriotic Alternative have shown up at the Crosse Keys (Homeland have denied being “far right, fascist or white nationalist”) — but there are signs they are no longer contained to the fringes of the movement. As of today, the Basketweavers have more than 2,400 vetted members worldwide, with 48 local groups in England. Maybe Houghton’s dream isn’t so far off.

* Names have been changed

You can buy Year of the rat: Undercover in the British far right here.

At The Londoner, we're proud of our investigations. But, put frankly, they cost money. To enable us to continue providing this kind of high-quality journalism, consider becoming a supporter for just £4.95 a month for your first three months.